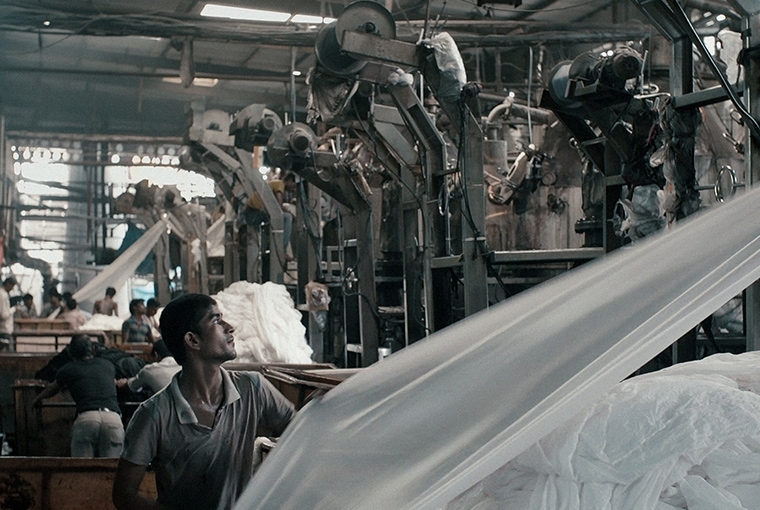

A still from Machines

A still from Machines

As a five-year-old, Rahul Jain spent his summers getting lost in the labyrinthine corridors of his grandfather’s now defunct textile factory. As a kindergartener, he was left overwhelmed with the machines. He remembers in fragments getting lost in the long aisles lined with printing machines, relishing the smell of coal maybe because it was forbidden for him to be there in the first place. All this pulled him back to the factory years later, as middle-aged adults still caught in the chains of exploitation. This time with a camera in his hand, Rahul observed how the workers toil their entire lives in these factories of exclusion and alienation. The exploitation finds its way into the factories where there is just one boss supervising a thousand workers - and favouring just a few. A lot is left unseen, and a lot is deliberately overlooked for the interests of a few.

The story moulded itself into Machines, his debut documentary that bagged two nominations—for cinematography and direction respectively— at Sundance, before travelling to IFFLA, with two other documentaries from India But that wasn’t before the Delhi boy studied in the United States at a military boarding school. He befriended films to cut through the alienation he felt there, and upon graduation came back to India and made a couple short films that got him through the film school of his choice, Cal Arts. Four years at Cal Arts introduced him to film aesthetics on a formal level. Currently, he is pursuing his Writing M.A. in Aesthetics and Politics.

Here, he tells me about working under utter panic, shooting strategies and all that went into Machines

When did you first come across the conditions of the textile workers of India?

For my first two years at Cal Arts, I couldn’t make anything because I was not really inspired or influenced by my immediate environment. I couldn’t identify with the people there. It was a very conservative white background. Then my teachers gave me an ultimatum and said I need to make some- thing or they would kick me out! I had heard in a class somewhere that when you’re not inspired, you can look at photographs. So I Googled ‘20 greatest photographers ever’, and got a book about each of them. Of these, I was really hooked on this book called Workers by Sebastio Salgado. And it made me think about all the things I wanted to say as a child but wasn’t able to, because I didn’t know how to. So then I picked up my camera and went to this factory that was owned by my distant family and I thought I could do something like the Workers.

Why did you feel the need to make a film on the subject?

I was curious about the class divide I experienced my whole life, growing up in a privileged family in New Delhi. I was always wondering that when my family was popping a bottle of champagne in a five-star hotel, our driver was making half of its price in a month. I was just always curious and couldn’t understand the economics. So this film came from there, and it also comes from the fact that my maternal grandfather owned a factory which has been defunct since 2001. I used to spend my summer with him in Gujarat when I was 10, and we used to live right above his factory. I used to go down with him to the factory since I was an infant and I’m sure deep down, even in my really early unconscious mind, I was able to accumulate my experiences of being in the sensorial, stimulating environment. I was able to remember my fascination with everything. It was not the machines I was interested in but the human beings, the way they were working. That might have affected how I was looking at the subject in many ways. When I made the first cut of the film and took it back to school to show to my teachers, they all started calling me a Marxist. The film was an accumulation of all my thoughts as a child and my feelings. I have actually thought about this subject my whole life.

A still from the film

How much time did you spend on the research and preparation for the final shoot?

We spent more than a month inside the factory, me and my DOP, Rodrigo Trejo Villanueva. And our deal was that we wouldn’t touch the camera that month. We would only have a pen and a paper. But he did have a still camera to understand the framing and every- thing. But we were in the factory for six months with three shoots spanning two months each. While I was simultaneously editing it, I made 85 cuts. It was an extremely slow process. I think the editing was the most difficult part.

The workers must have been very uncomfortable around the camera. How did you gain their trust to establish yourself inside the factory?

Intimacy is a two-way street. If you expect it from someone, you must be willing to give it to them. I was able to understand this fact very early on, and I explained why I was there, why I wanted to do this...where I was trying to get at and what my motivations were. They were very fascinated with the camera actually, because no one had ever taken a photo of them. These people are not used to being represented on screen in any way, so if anyone does that, they would get disturbed. It took them a few weeks; I used to leave the camera with them staring at it. They just wanted to feel safe I think.

What were the conversations you had with your cinematographer?

Rodrigo and I were best friends since film school. Our ideas about cinema are similar. We talked a lot about time or temporality, and how we wanted to use time as one of the primarily determinants of the images in the film. We were really fascinated by classical com- positions in Renaissance paintings particularly by Caravaggio. He was also very fascinated by darkness, and this factory had a lot of that. The colours were really dark. We tried to aestheticise all the things that are ugly in real life and make it beautiful. My idea was that if it won’t be beautiful, it will be easy to look away from. This film and its subject is so heart-rending, it hurts your soul. We look away from such things that are happening in everyday life, even though we know they are happening.

Were your views altered in any way during the process of the filmmaking?

My mind did change about the fact that these people actually wanted to come here and work, and they were really happy to work there. That they were thankful to their bosses...they were thankful to their managers for giving them a job. Their situations and circumstances were so dire that they were open to the idea of being completely exploited. They didn’t even consider it exploitation. This was something new I learned during the process, because I went in there with a black and white perspective. That this is just wrong— but I was forcibly changed. I realised that these people are coming from the poorest parts of the country where there are literally no prospects, so parents would be happy to send their kids so that they can feed themselves and earn and maybe send a little back home.

What were the challenges you faced?

I felt really alone, like nobody could understand what I was doing for a long time till I had already worked on 85 different cuts. If I make something again, it would be good to have a good support system. There are no good Indian producers who want to make good work anymore. They only want to make work where there are monetary viabilities. It’s very unfortunate. I’m trying to find someone to fund my next film and I have to look outside to make a film in India. I’ve been out most of my life but I still feel some affinity towards India but the outsiders will never feel that. They can have compassion for the other side but they won’t ever feel that they belong here or they do need to do something. I had to devise my own language because I didn’t take any kind of reference from anywhere; maybe photography wise, yes. In terms of aesthetics, yes, but in terms of structure, in terms of the meaning of the film, I really had no clue how to say it. Having a producer or a line producer makes a difference, but it was just me, my cinematographer and my sound designer. We were working all day, night shifts. But I keep hearing again and again from big documentary filmmakers that producers are never going to back you...it feels disheartening to hear that.

Would you call yourself an activist now?

I’m a filmmaker and I will be making films about the things that I don’t like about the world, and that might be considered being an activist, but I hope deep down I stay a filmmaker. What drives me is feeling suffocated. I feel that I have no other option but to say it out loud with the medium of my choice. I don’t think artists can be activists.

Where is the film headed now?

The next film festival it will go to is called Frame Representation in London and then it will travel to Hotdocs before coming to India with MAMI.

Are you working on something new?

I’ve been working on a triptych about - land, water and air pollution in the city of New Delhi.

Text Hansika Lohani Mehtani

Rahul Jain