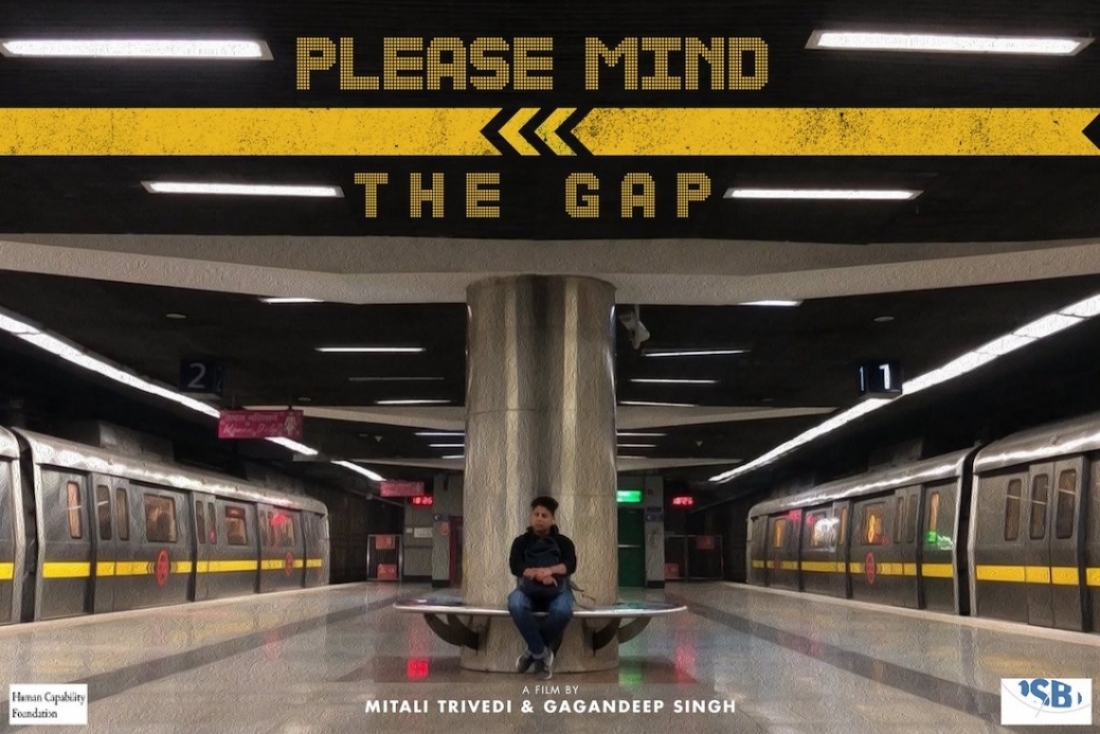

Please Mind the Gap is a documentary that first made its way to the screen by seeking funding from Public Service Broadcasting Trust. Shot on a Google Pixel, and directed by Mitali Trivedi and Gagandeep Singh, the film tells the story of a happy and opinionated transman – Anshuman. The film moves through the space of the Delhi Metro and attempts to understand how gender is performed within that space. Platform speaks to the director Mitali Trivedi to know more.

How did the idea of your film “Please mind the gap!” come about? Did you always know the film was going to turn out the way it did?

The idea was very different in the beginning. We wanted to work on the act of queer couples holding hands in the Delhi Metro. The act of holding hands is also an act of love and an act of resistance at the same time. But that did not work out well visually because I am a first-time filmmaker, and I did not know how to deal with subjects. It just felt like anything that is good on paper would be good visually too, but, of course that doesn’t happen. So it wasn’t working out very well. In this process, we met Anshuman. From there on, he was always our reference point to meet other people. But soon we realized we have a comfort with him. And then we just started hanging out with him, without thinking that we might work with him.

In a way, there are two protagonists in the film – Anshuman and the space of the Delhi Metro. Why did you choose to make the film around the interaction of the two? Why did you choose to work around the space of the metro?

I did my Masters in Gender Studies and I did my Bachelors in Economics. The shift was very impactful. In Economics I was learning numbers and statistics, and in gender studies everything was related to my immediate reality. “Why does my mother cook at home?” - were the questions that started bothering me instead of stats. And after classes I would just take the metro back home. I would apply everything I studied in class to the space of the metro. So from the moment you enter, the metro divides you into two spaces – women and men. So the metro felt like a little world we had created within our world where the notions that are applicable here, are also there. It felt like a film could work in this space. And also, people haven’t really worked on the metro as a gendered space. You only see it in passing in Bollywood films or documentaries. But nobody ever tried to stay in that space. So, we thought it would be interesting to see how gender is performed in this space. Also, we understand the metro as the most modern and the most updated form of transport, right? We think the more updated and modern we are, the less these categories of gender, class and caste would affect us. But that is not true! Even though the metro is the most modern way of traveling, it still divides us. And sometimes it is so invisible in these spaces that we can’t even put a finger on it. It’s that enmeshed with the space. The space of the metro also constantly instructs us. There are instructions like – Khaana matt khao, gaanay matt suno. So if you have to travel in the Delhi Metro, you have to act a particular way. Otherwise, it is not a good mode of transportation. They try to discipline you. It is also a mode of transportation that is spread everywhere. Starting from Rithala, the metro takes you wherever you want to go. So, we thought it would be interesting to see how someone negotiates through this space.

Film Still

Your film begins with a warning that explicitly tells the audience that it is illegal to shoot inside the metro. How do you think that impacted the cinematography of the film? Were there barriers? Would you have some anecdotes to share about the same?

The decision to put that warning at the beginning of the film was a decision we took while editing the film. We thought we will just put it out there that there is a rule like that. Even after knowing that we continued the shooting without permission. We wanted to put our politics out there. We did not seek permission to shoot. So, we shot on a phone right? The film is shot on Google Pixel. And soon, we realized that you don’t get caught as much as you thought you would. This is because phones for the janta are a huge part of that space. The moment you enter, you’re on your phone. And if somebody is on their phone and shooting, it isn’t very visible. It seemed then that our phone was just a part of that space. And if one used their phone in a particular manner and shot from certain angles, then nobody really noticed. So, initially we were very scared. But once we started shooting we realized nobody was really looking at us. And we also kept out crew very small. At one point of time there were only two to three of us. The entire film is made by three to four of us. And since it was just two to three people at one time, one of us would look out and just check to make sure that nobody’s watching. One of us was just behind the cinematographer looking at the angles. And this is because the space of the metro is chaotic and full of people. You cannot even be sure if your angles are coming out right. This is how the cinematography was challenging.

But, we were caught a few times. Of course, we were caught. Once, our cinematographer was shooting at Rajiv Chowk. The station has a place where if you go, you can see the whole station under you. We were trying to shoot that on the blue line. And it was there that some girl spotted him and told the CRPF that someone is shooting. So, a group of four or five people arrived and, in that moment, we instantly exchanged our phones because we didn’t want to lose the footage. I moved away because I had given my phone to him. Then when they arrived, they started asking questions like – “What are doing?!”, “Why are you standing here?”, “Are you shooting?”, “Are you taking pictures?” And he just said, no, I was just playing Candy Crush. Then, they asked for his ID. Since he had his college ID, they let him go. Once, I think some guy inside the metro figured that we were trying to shoot. And, he came and snatched the phone from the cinematographer. He started getting very aggressive. All of a sudden, Anshuman started abusing that guy! He said, “If someone is shooting me, then what is your problem?” Then the matter at hand was to calm Anshuman down, and then the rest of the situation were to be handled. It was a chaos. We didn’t expect Anshuman would start fighting. So, in that moment were a little taken aback.

Film Still

Anshuman’s presence in front of the camera reveals a very strong sense of comfort. How did this comfort with Anshuman develop?

As I mentioned, we’re all first-time filmmakers. And we have all loved cinema for a very long time. We never thought we would actually make a film, but it was just a lingering thought that we had. If you’re a writer, you always think maybe I could write a script like that. It is almost as if any skill you have, you want to put it to use and make a film. We were those people too. So, PSBT had a proposal for gender related subjects. The film was supposed to be 10 minutes long. Since I hold a Masters in Gender Studies and 10 minutes seemed like a duration that I could handle. And as I mentioned, the idea at the beginning was very different and it got approved. We had a lot of inhibitions. We thought, we have the money, but now how do we use it, what do we do? None of us really had a clue. None of us did editing, none of us knew the camera. All of us were first time filmmakers except our editor who we found later. But otherwise, both my codirector are cinematographers are lawyers. And I was doing my MPhil on Sociology. So, we were just a bunch of students. All of us all do theatre. That was the one common thread. Since we were all students at that point, we thought let us just collaborate on all the research skills that we have, and the theatre skills we have and combine the two to make a film. Then we decided that we will not shoot until we are comfortable with the person. Because otherwise, it is just unfair. For a year then, we did nothing except hanging out with Anshuman. Luckily, he lived very close to my house. And after a while, he just started asking us – “Are we even making the film or not?” He said, “All we do is have chai, and sandwiches and then go back to our places.” After a year we thought he is a friend now. We forgot that we had to make a film, and this and that. Anshuman was longer a transman. He became a friend who loved chocolate shake. Those ideas about shooting a film simply went away and he just became a part of our lives. So, when you work with a friend you see them a particular way. You don’t think that you’re going to look at their gender identity, their trans identity. You accept them for who they are. And now, Anshuman knows as many stories about us. Tomorrow, he could make a film about us. Then we decided it was time to shoot. With Anshuman, it did not take a lot of time. We were done within two days. And this was because we already knew the stories. We knew him. He knew us. The metro was ours because we travel in it every day. Nothing was unfamiliar. We were just going with the flow after a year.

Both you and Mitali come from a strong academic background. How did you think your expertise complemented the process of filmmaking?

I think research skills help you a lot. When you research on something, you look at one particular thing from ten angles. That is how research trains you to think. One thing is not simply one. It is multiple things for multiple people. And that is what we wanted to do. We already knew that there was a stereotype within the documentary space about queer identity. Questions such as – “When did you come out?”, “When did you tell your family?”, “When was the first time you realized it?” These five to six set questions we did not want to do. I hate these questions. People are more than just one identity, right? I am more than one person. So, this is how research helped us. Another thing that really helped us was theatre. I think theatre teaches you comfort. It tells you that you become so involved with people that after a while, you perform like a family. You rehearse so much. You talk so much. You communicate. You have chai.

What’s next for you now?

We’re in the process of looking for funds for more documentaries. The documentary funding system is very niche. And the money is very less. There is also a particular stereotype that is there for documentaries – that they’ll be educational in nature, won’t be entertaining, that it will be about a particular subject, and this and that. In order to break that, you need to have some form of financial support. There has to be some motivation. It is only fair to expect payment for your work, I think. So, we do have some ideas, but now we need funds. The struggle is on! We might move away from queer identity as well and explore a different space. We don’t want to tell the same kind of story.

Text Muskan Nagpal

Mitali Trivedi