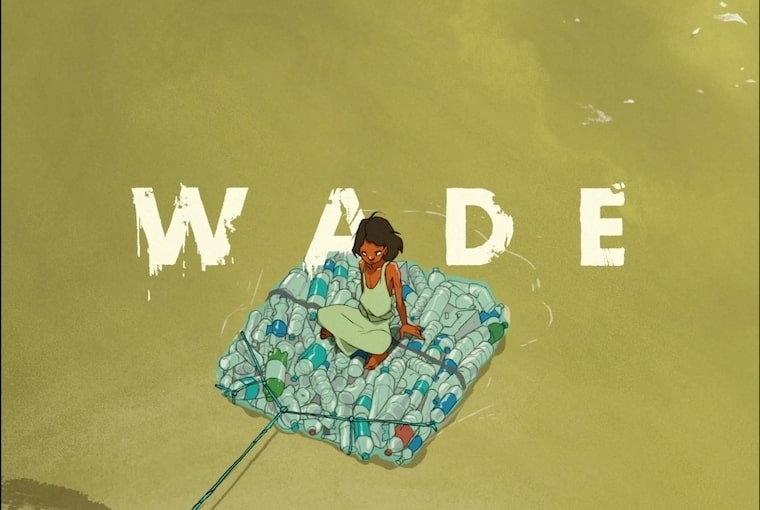

Wade is an animation film that depicts a very moving, climate change horror story. The inhabitants of an entire city, which is swamped with waist-deep water, flee in fear, leaving behind a few to fend for themselves. It is the survival of the fittest. Kolkata’s famous Park Street plays as the setting to the film, with all locations made to look as real as possible, except of course being inundated with water. We get to watch the people, the trail of filth and garbage we leave behind us in a situation that is far too possible.

Animation is a very meticulous and time consuming process, with each and every frame designed and detailed one at a time. Wade was in the making for about four years before beginning its extremely successful festival run — it recently played at the Palm Springs International Festival of Short Films. Kalp Sanghvi and Upamanyu Bhattacharyya, who met at the National Institute of Design, ventured to bring together a bunch of supremely talented animators and create their company called Ghost Animation. The animators worked tirelessly, often sleeping in shifts to give us Wade. It’s a very important film, especially in times like these when the climate change crisis is only getting worse. We spoke with Kalp and Upamanyu to know more about the film and also why our country has so many talented animators but not enough homegrown animation.

Could you tell us a little about where the concept of Wade came from?

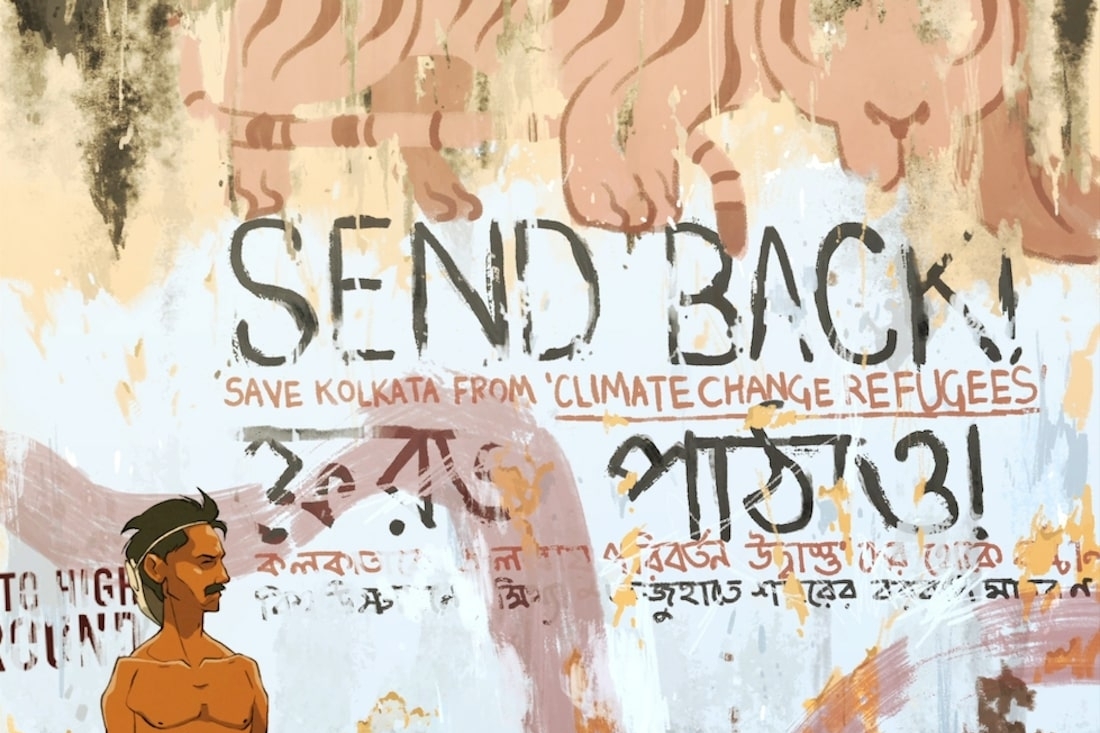

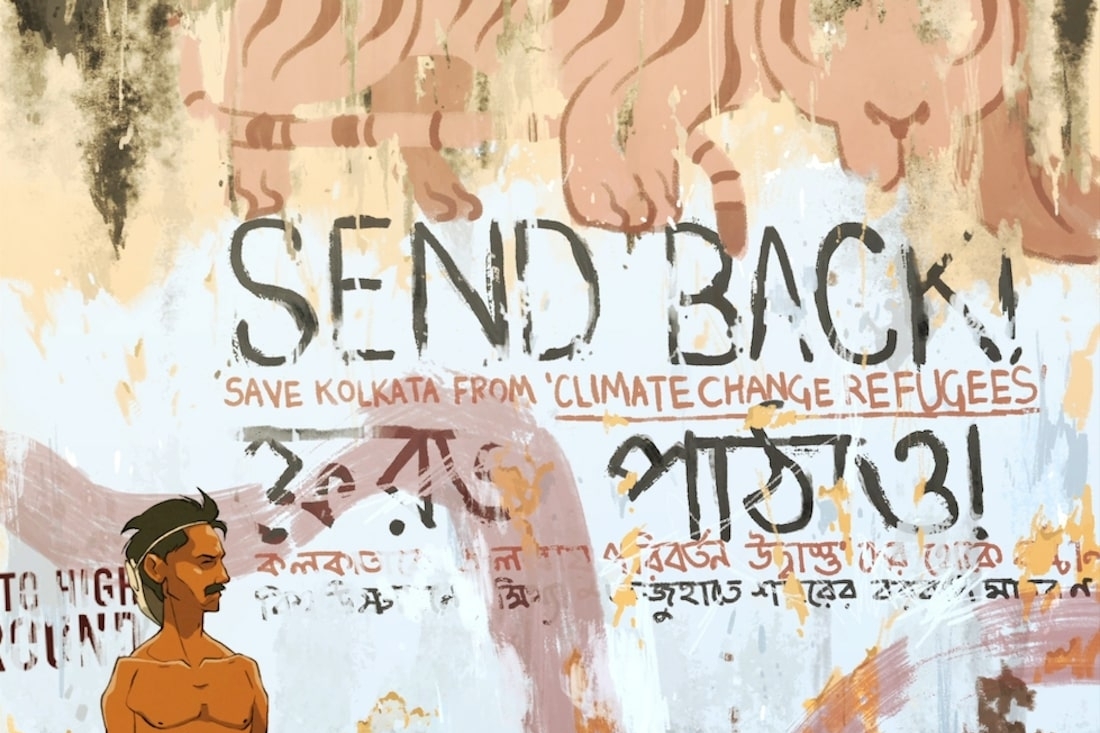

The concept originated from an article we came across, which spoke about the Ghoramara River Islands in the Sundarban Deltas, just south of Kolkata, drowning due to sea level rise. Hundreds of families have been displaced and have nowhere to go. We know that climate change is real and Kolkata is next in line. This idea really scared us and what it would do to Kolkata. The ones who can afford to move out will, but the ones who will suffer the most will likely be the ones who contributed the least to global warming.

Would the people of Kolkata welcome the refugees into the city for safety, understand them? When the flooding begins, how many people would stay in Kolkata, and how many could or would leave? The questions turned into bigger, scarier questions, which we tried to address in the film.

Please tell us a little more about the setting of the film and what informed your decisions regarding it.

Park Street is sort of like the NYC Times Square of Kolkata. We took a lot of photos of the city that would inspire our backgrounds, especially the opening montage. We decided to set most of the action in Park Street because of the wildly recognisable Flurys, so that the bright pink could act like a ghost of happier times for the city. It was very important that the city be recognisable to those who know it, and not radically sci-fied, so the situation feels even more tangible. Both of us, being from Kolkata, we knew we wanted the film set there. Like we said earlier, Kolkata is right at the head of the line to suffer the effects of climate change. We’ve seen such imagery already during the pandemic and the cyclone. It’s not science fiction.

Animation comes with a lot of brain drain and strenuous work. Tell us a little bit about your process.

Yes, the process of making a film by drawing one frame at a time often feels counterintuitive. We start with a storyboard, lock our edit and then just go for it — animating the outlines, colours, shadows, stripes, drops of water and so on, until it inches towards completion. It involved a lot of people being kind enough to give the film their time and talent, and we learnt a lot about production management along the way too. Breaking up a large task and making it seem achievable is invaluable to the animation process.

Do you think that Indian audiences aren’t willing to pay good money for good animation unless there’s a commercial brand attached to it? Why do we have so many incredibly talented animators, but not enough homegrown animation? What do you think the audience wants?

Audiences anywhere like a good story, and Wade has been very well received in India! Our studio produced three other short films other than Wade last year which have toured the entire country — they’ve been screened at 28 completely sold out venues. Completing an animated film is very tough, and selling it when it’s done has way too many dependencies. Usually there’s little to be gained in griping about the audience, all we can do is commit to making more films that we feel we’ll enjoy making and see how it goes.

Wade began with a very successful funding journey four years ago, and now it’s ready for the world to cherish it. Other than the funding, was it challenging to get it to the right platforms? Where do you hope the film ultimately reaches?

All concerns such as ‘will this film get funding’ or ‘will it get into festivals’ is just a variation of ‘will people like the film,’ which is a universal artistic anxiety and a challenge to every filmmaker. It’s often tempting to not risk putting it out there and hearing all the potentially unkind reviews in which three years of work gets erased by one dismissive sentence. Usually after the first couple of hits and misses (there are several misses), the hits tend to snowball and lead to something good. Even though most of the festivals have shifted online this year, it’s been great to see the film’s audience grow. It’s good to see people from around the world regardless of background and language engaging with and relating to a climate change story set in Kolkata. We only hope it affects people enough to begin imagining their own lives after the climate crisis.

Lastly, is there a new plan/film/project in the works?

Yes! At Ghost Animation we just completed three other short films besides Wade and are finishing four more this year. We're also working on a series, Rajbari: The Ancestral House, a fantasy family drama set in Kolkata, and a feature length film City of Threads, set in Ahmedabad in the 1960s.

Text Hansika Lohani Mehtani