Almost two and half yeas ago, a group of like-minded women got together in the city of Islamabad and decided to indulge Jane Austen’s work over tea and scones. Today, the same group of women have evolved into a literary community that has chapters in some of Pakistan’s major cities and an enthusiastic social media engagement of 1700 people from 45 countries.

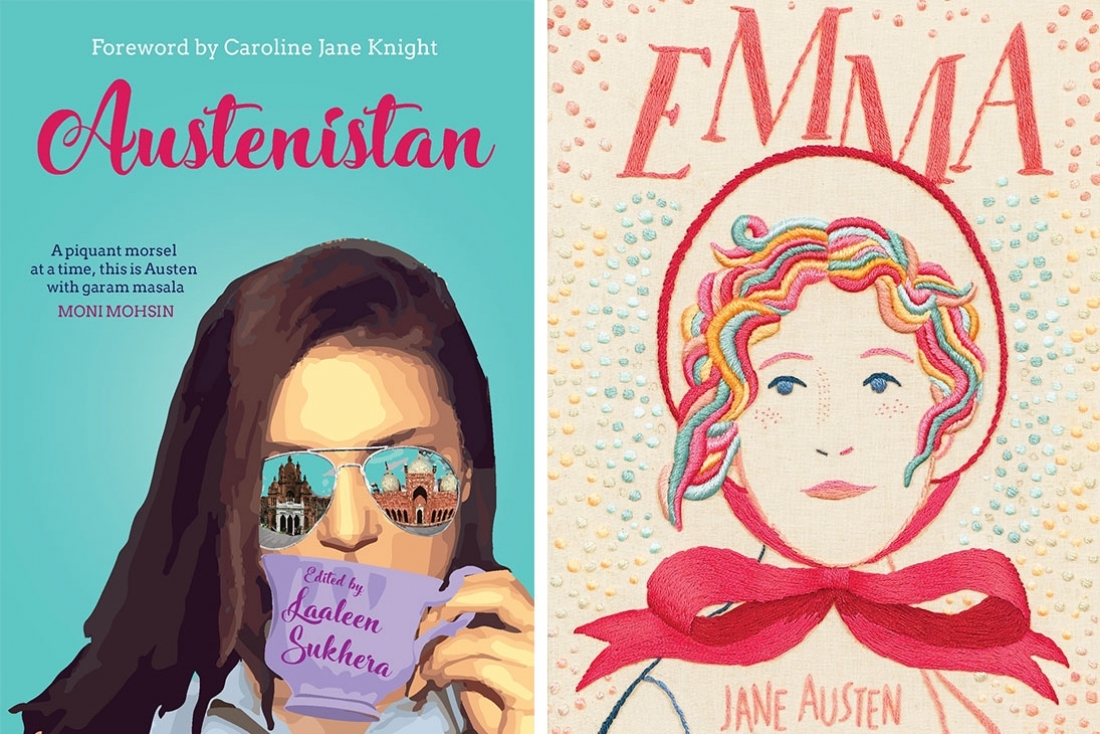

The Jane Austen Society of Pakistan is making Austen relevant once again with the release of an anthology called Austenistan. Edited by Laaleen Sukhera, it is a collection of seven short stories that are inspired form Jane Austen’s notable works. Austenistan invites readers to reimagine Regency England in a contemporary South Asian context and get a peek into the lives of Pakistani women.

Laleen Sukhera, Editor

Austentistan—apart from being an obvious play on the words Austen and Pakistan—is a testimony to Jane Austen’s timeless work. An exploration of the lives of women in contemporary Pakistan; their relationship with themselves, the people around them and the struggle of having to mould oneself to fit into a society that was never meant for them. ‘As Pakistani women, we have limited choices and freedom over our own lives and we have to come to terms with that. At best, we can either work the system or shake it, but we can't seem to change it,’ says Mahila S. Lone, one of the contributors of the book.

More than just being a revamped version of Austen’s novels, these stories bring the writers to the front line and are a microcosm of their relationship with modern-day Pakistan. Contributor Gayathri Warnasuriya, in her story The Autumn Ball, longs for the familiarity of a ‘home’. Just like the protagonist, she too has lived the life of a nomad, “I actually relate to Maya. I make a new home for myself every three to four years and my permanent home is still my parent's house. However, my country and I have changed so much that I often feel, in the words of Ijeoma Umebinyuo, "too foreign for home, too foreign for here, never enough for both”'.

With every story beginning with an original Jane Austen quote, the anthology is reminiscent of Austen’s works not just in terms of the plot, but also in how smoothly it transports us to modern-day Pakistan. What’s more interesting is how one story can be reinterpreted to fit multiple different contexts. Saniyya Gauhar’s The Mughal Empire interprets Pride and Prejudice from the point of view of Ms. Bingely, who doted on Mr. Darcy for the longest time before taking off for London. “I was intrigued by the line towards the end of Pride and Prejudice that Miss Bingley was ‘very deeply mortified by Darcy’s marriage.’ I wondered how such a proud character would have felt in the aftermath of Darcy’s marriage.”

Undertones of real life misogyny, the growing use of social media, and power structures between gender binaries are dominant themes throughout the book, but the focus remains on female friendships and protagonists as they try to navigate their way through their personal turmoils. “More than the love stories, it is the strength of Jane Austen's female friendships that gave her books depth and ability to withstand the test of time.” says Mishayl Naek, the writer of Emaan Ever After.

We speak to the founder of JASP and editor of Austenistan, Laaleen Sukhera about her experience doing the same.

Most of the stories are based in a slightly affluent setting. How are true are these portrayals for Pakistanis not belonging to such prosperous families?

Our stories reflect a segment of our society as we see it, but with a fictional lens. They are for readers anywhere in the world and do not claim to represent anyone. However, I’d say that many aspects about romantic relationships and social struggles permeate socioeconomic differences. For instance, the abusive behaviour described in Only The Deepest Love is not restricted to a particular social class as it affects everyone.

Why Jane Austen?

Jane is phenomenal, her work transcends time, she is so English and yet so desi. What’s not to adore?

Austen’s portrayal of society is so relevant to that of contemporary Pakistan—is this a good thing?

We find the parallels relatable, fascinating, and even frustrating at times. It’s almost laughable that we still experience similar levels of misogyny as women in England did two centuries ago.

Austenistan’s narrative focuses on relatively affluent Pakistani women. Was this a conscious choice?

Several of our protagonists do not lead a privileged existence despite their educational qualifications. If you take a look at The Fabulous Banker Boys (the Baigs are struggling with their daughters’ tuition bills), The Autumn Ball (Maya is mocked for her parentage), and Only The Deepest Love (Samina cannot afford an airline ticket on her teacher’s salary). Even protagonists who appear outwardly privileged may inwardly be fighting their own demons—whether it’s Kamila’s deep-rooted insecurities in The Mughal Empire, Emaan’s trust issues with men in Emaan Ever After, or Saira’s social rejection as a widow in Begum Saira Returns.

What about Jane Austen inspires you?

I was inspired by Jane’s own life—despite practical opportunities for matrimony, she grew picky when her heart wasn’t in it, and ended up remaining single and writing for a living. Quite a feminist! If she was alive today, she might well have been a blogger.

Additionally, I was inspired by situations that modern-day Austenian heroines might find themselves in when being induced to marry well by societal expectations. Like a self assured, high maintenance Emma Woodhouse who might be tempted to marry if a man ticked all the right boxes. But when it comes to reality, so-called eligible men are never as wonderful as they sound on paper, are they?

What does Austenistan hope to inspire/convey?

Humour, empathy, curiosity, and awareness about South Asia to the rest of the world!

Text Pankhuri Shukla