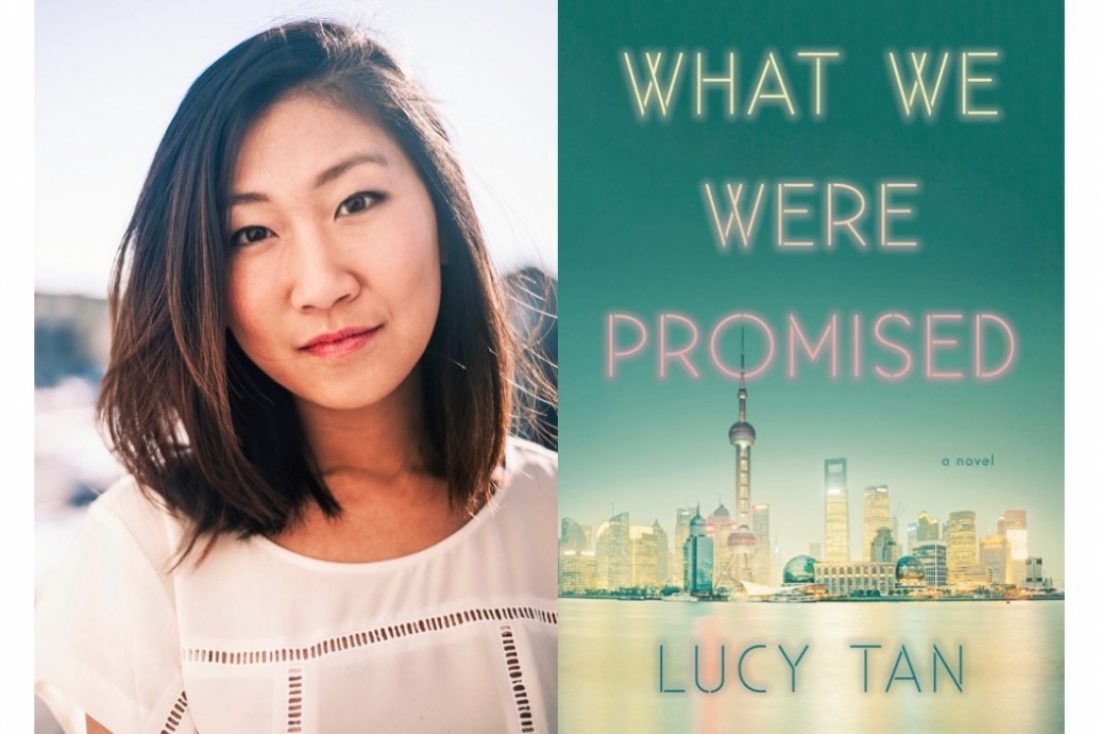

As an only child, Lucy Tan craved human connection, but felt most herself when she was alone. Writing gave her a way in to both, at once. ‘Through use of words, I could access identities and emotions that were closed off to me in the real world. Writing was transportive; I wrote both to escape my reality and to deepen my understanding of it.’ Having a librarian mother, Lucy spent hours after school in the library. ‘I read everything from 1970s’ YA fiction [which forever complicated my understanding of sex and dating] to Stephen King’s psychological thrillers. I have always been interested in the ways people relate to one another, and reading was a way to investigate further.’

A lot of her writing is taken from her own reality; it could be a personal experience, an image, an interaction or a place she visited that invariably makes its way into her fiction. ‘Writing fiction is a way for me to explore my preoccupations. Even if the characters and situations in my stories are made up, my invented realities exist alongside my lived reality in my mind. They are different, but they share the same DNA. Writing is my way of looking more closely at something and from a different perspective. This kind of intensity sometimes dislodges the real experience from my brain, to the extent that I won’t remember which experiences I’ve lived and which I’ve written.’

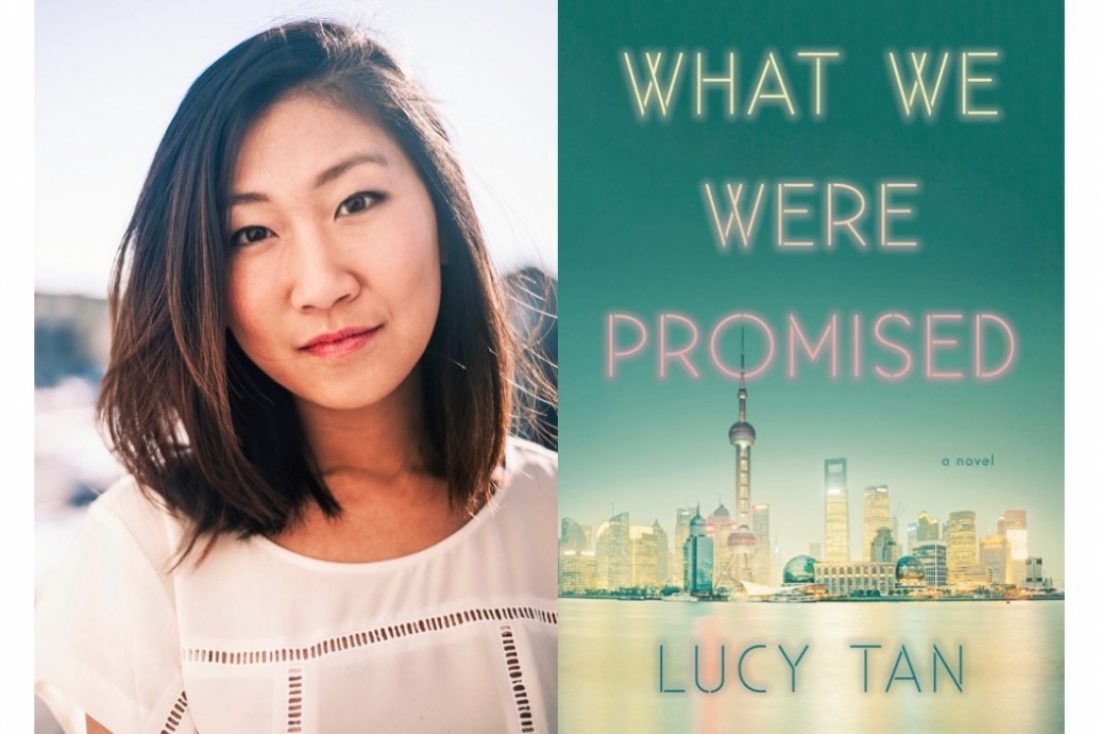

All ready with her debut novel What We Were Promised, Lucy shares pages from her life that co-exist in her book.

What inspired your debut novel, What We Were Promised?

I spent two years after college living in Shanghai with my parents, who were working there as American expats. Having visited China since I was a child, I was surprised by how much the country had changed. In Shanghai, Pudong New District was crowded with skyscrapers and the smog was sometimes thick enough to obscure everything beyond a hundred-meter radius of where you were standing.

I grew up middle-class, and it was a culture shock to find myself living in a luxury-serviced apartment, an expense covered by my dad’s job. We had maid service every day and ate catered breakfast in the resident lounge. It was in this serviced apartment that I met many of the people who would inspire characters in my novel—housekeepers and waiters, drivers and tenants. The class and cultural divides were astonishing, and I wanted to capture this moment in time, which felt like another turning point in the span of China’s long history. I wrote What We Were Promised from multiple perspectives as an attempt to capture the breadth of experience in modern China today.

Can you give us a blurb on the book?

Set in modern day Shanghai, What We Were Promised introduces several generations of the Zhen family. Wei, Lina, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Karen, find their lives upended when Wei's estranged brother, Qiang, shows up after years on the run with a local gang. His arrival marks the unraveling of long-held family secrets, witnessed closely by their housekeeper, Sunny.

From a silk-producing village in rural China, up the corporate ladder in suburban America, and back again to the post-Maoist nouveau riche of modern China, What We Were Promised explores the question of what we owe to ourselves, to our countries, and to generations past.

“It was important for me to tell What We Were Promised from a Chinese perspective, one that does not dismiss the Cultural Revolution outright as a foolish tragedy but understands it within the context of China’s war-ridden history.”

You say the book explores the question of what we owe to ourselves, to our country and to generations past—all the above leads to a sense of belonging and home, so if you had to—how would you define Home?

As the world becomes more digital and people more transient, communities can be found in non-physical spaces. I think of “home” as a set of relationships with people, language, and cultural norms that culminate in a sense of identity. What are your influences? What are your values? How would you tell your origin story? Considered this way, home is not where you’re from, but where you feel most yourself.

The Internet has been a great resource when it comes to connecting like-minded people and allowing communities to build homes online. However, it’s a double-edged sword. It also makes it easier for each of us to withdraw into the places where we’re most comfortable. The results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election have shown just how different American values are and how little we know about our neighbors’ experiences. I guess what I’m saying is that home is important, but so is travel. We owe it to ourselves—and to our countries—to understand how others live and think. I long for a world in which everyone makes the effort to travel to other communities, online and off.

What kind of research went into your book?

I conducted interviews, both formally and informally, with people I met in China: locals, expats, migrant workers, and family members. Oral history is an important aspect of my book because many stories from my grandparents’ and parents’ generation remain untold, due in part to oppression and censorship laws at the time. My grandparents lived through the Japanese occupation and my parents grew up during the Cultural Revolution. I think of them as living relics, and take opportunities to record conversations with them as often as I can. I ask them what they ate, where they lived, and how they felt during important moments in their lives and in history. Their answers often surprise me and remind me that my understanding of China is filtered through the lens of American education and bias. It was important for me to tell What We Were Promised from a Chinese perspective, one that does not dismiss the Cultural Revolution outright as a foolish tragedy but understands it within the context of China’s war-ridden history. I have learned a lot about why such a movement felt necessary at the time, and what we can still learn from it today.

“I had no expectations about living in China, but the outcome was that I left having formed a personal relationship with the country—one that was unmediated by my parents’ experiences. In other words, my heritage felt less inherited and more earned.”

You spent two years living in Shanghai and that experience culminated in What We Were Promised. What were some of the discoveries you made about life there, and about yourself, in those two years?

I moved to China with two goals: First, to explore the country where my parents grew up, and second, to pursue fiction writing professionally. I knew I loved to write, but also that I had been dependent on classes and workshops. I wanted to see if I had the discipline and drive to continue on my own.

I obviously wasn’t ready to become financially dependent on writing, and while in Shanghai, I held the following jobs: copyeditor, TV talk show co-host, voice over actress, legal intern, essayist, educational content writer, English tutor, and college admissions aide. What started as career flightiness became an act of collecting experiences for later use in fiction. I wrote a lot of fiction while I was in Shanghai—not stories that would eventually become What We Were Promised, but ones that helped me build skills I’d later need to tell this story.

I had no expectations about living in China, but the outcome was that I left having formed a personal relationship with the country—one that was unmediated by my parents’ experiences. In other words, my heritage felt less inherited and more earned. That was a rewarding feeling.

Lastly what are you working on next?

I’m working on a second novel about three friends and aspiring actresses who grow up in Wisconsin. I spent a couple years there as a graduate student and a theater actress, and the place has captivated me ever since. This fall, I’ll be heading back to the Midwest for a position as a Fiction Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing. I’m excited for the chance to research and write my novel in the place where it’s set.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra