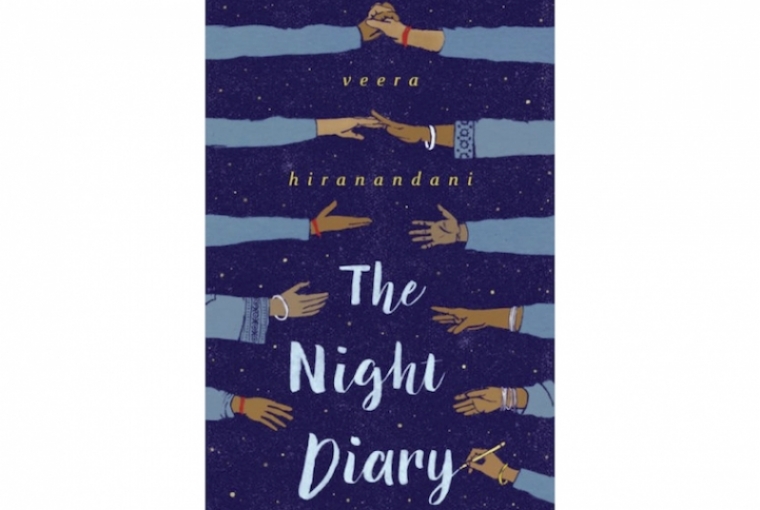

The author of The Whole Story of Half a Girl (Yearling), which was named a Sydney Taylor Notable Book and a South Asian Book Award Finalist, Veera Hiranandani has now released her new book, The Night Diary, which was featured on NPR's Weekend Edition and is a New York Times Editor's Choice Pick. A former book editor at Simon & Schuster, she now teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College's Writing Institute where she had also earned her MFA in fiction writing. Her new book, The Night Diary, is a haunting story born out of one of the most dramatic moments in history of the world, the partition of India and Pakistan, resulting in one girl’s search for home, her own identity, and a hopeful future. In conversation with the author here about her relationship with writing and the story behind The Night Diary.

How did your relationship with writing begin and how has that relationship been so far?

I think I turned to writing for a few reasons. I was always a creative person and making things like art, food, and stories made me feel powerful when I was young, because I often didn’t feel that powerful in my daily life. Writing helped me understand who I was and figure out the world. I wrote bad poetry, short plays, prose, and kept journals. I didn’t start writing more serious fiction until college. That’s when I also started thinking about writing as a career path.

A year after I finished college, I entered a graduate program for writing and fully immersed myself. I wrote an adult novel in my program, but never tried to publish it. It wasn’t very good and I was still so young. I kept writing, however, and many jobs and two kids later, I published my first novel for young readers, The Whole Story of Half a Girl which was based on some of my experiences growing up with an interracial and interfaith background (Hindu and Jewish). I’ve also published a chapter book series and The Night Diary. As I’ve grown as a writer, I find that I’m more and more interested in how people navigate multiple identities and living in the margins. In my small town, I stood out and never felt fully accepted. I turned to books to keep me company when I felt alone. I feel very lucky that right now I get to write and teach writing full-time, but even if I wasn’t able to, I still would write. It’s just a part of how I go about living.

Can you tell us about the writers who have influenced you and your work and in what ways?

Growing up, I read the writers who were available to me--Roald Dahl, Beverly Cleary, E.B. White, Sydney Taylor, and Judy Blume.They are all great storytellers, but I was always searching for characters that reflected my life and my identity more closely. I didn’t find much back then, which is a big reason why I write the books I write. I’m writing for that lonely girl who needed these books. In graduate school, I fell in love with Jane Austen, Paul Auster, Fitzgerald, and Raymond Carver, but still something was missing. In the last fifteen years, I’ve read much more diversely and have shifted my focus to many South Asian writers to make more connections. Some of my favorites are Jhumpa Lahiri, Arundhati Roy, Mohsin Hamid, Salman Rushdie, Kiran Desai, and Manil Suri.

For your novel, The Night Diary, you chose a subject as heavy and complicated as Partition. Why did you choose the subject and what was your creative process behind dealing with it?

I’ve wanted to attempt a story set during the Partition for a long time. It was always with me growing up. I heard stories from my father and his family about how they had to leave Mirpur Khas, Pakistan in 1947 and find a new home in Jodhpur because of Partition. Yet I didn’t really understand what happened and why. In some ways I still don’t, but I know a lot more about the factors at work. I felt like it was an important story to tell for many reasons, but I was intimidated. Could I write a historical novel? Could I blend both my father’s experiences and other research to create a meaningful story that could explain some of the history but also be engaging for young readers so this history wouldn’t be lost? What point of view did I want to take? A few years ago, I finally gathered up my courage and went for it. The fact that it relates to some of the issues our current world is facing—the global refugee crisis, or the divisiveness, racism, and xenophobia that is felt in the US and many places internationally right now--is something I started connecting during the writing process, but not the main reason I wanted to write the story at this moment. I was just ready to tell it. I had many conversations with my father, and other relatives about what they remembered. I read history books and novels that covered the history. I watched films. I listened to oral testimonies online. Then I started writing. At the beginning, I was interested in creating an interfaith (Muslim and Hindu) family. For me, there was no better way to directly access the many questions I had growing up. I would write for a while, and then often I would come to a road block in my research and knowledge. So I’d do more reading, online research, or have a chat with my dad, and then continue.

The book is written through the perspective of a little girl Nisha who is writing to her mother through a journal. Why did you choose the narrator to be a little girl and how hard is it to write a novel by merging it with journal writing?

I think because I had grown up hearing stories from my father, uncles, and aunts about their childhoods in India and what happened to them during the Partition, it made sense for me to have the main character be a child. Children in tragic events are so at the mercy of the adults making decisions around them, and I understood that feeling somehow. Nisha is very shy and doesn’t like to speak in public, so if the reader were to hear her journal, they would be watching a new Nisha unfold, a Nisha that had never experienced the full power of her voice. It was hard, but I like putting boundaries on myself as writer. It forces me to think more carefully about my choices. At times, I decided to have her narrate a scene more fully than a twelve-year old would probably do in a real diary. I hoped the reader would want to take that leap with me for the story’s sake.

You have dedicated this book to your father. Would you tell us why?

He supported me so much during the writing of the book. I didn’t know how he’d feel at first--telling me his story and then watch me change it into something else. I think he was surprised at my interest in his life and Indian history, but ultimately very proud. I don’t think I would have taken on the subject of the Partition if I didn’t have this familial connection to it. During the writing of this book, I would look at pictures of my grandparents who died before I was born. I would look at my father as a young child with his sisters and brothers, and wonder what it felt like for them to have to leave everything behind not knowing what was waiting for them over the border. My dad is my link, my main inspiration for writing it. I also wanted to make sure I preserved some of this history for younger generations. There’s so much we can learn from it and the survivors are in their last decades of life.

When you researched for this book, were there any instances that you personally found had a big impact on you?

I listened and read many oral testimonies during my research. I wanted to know what it felt like to go from Pakistan to the new border of India and what it felt like to go from India to Pakistan. I wasn’t writing non-fiction. I was writing a story, trying to get to the heart of how it might have felt for this particular family. I wanted to look at the similarities and differences of people’s experiences going in different directions--Hindu families, Muslim families, Sikh families. The stories I read and heard all have their specific and unique details. Some people survived unimaginable violence and loss which was hard to take in. Others made it safely, like my father’s family, but still lost their old lives and had to rebuild. The confusion and sadness about how peaceful diverse communities could break apart and turn violent so quickly was usually the biggest question in every story I heard, no matter what faith or what direction of travel. And it broke my heart every time. It made me understand even more how vulnerable we are to our own humanity.

As a writer, do you find the subject of your work to be more important or the way it is written?

Interesting question. I don’t think I can separate the two. Both are equally important to me. It’s sort of like looking at a painting of a chair. It matters that it’s a chair, but it also matters how it’s rendered. A detailed black and white drawing of a chair says something much different than an abstract oil painting in pink and green. I try to do more with less and use economy in my writing. I greatly admire other writers who are successful at this.

Lastly, are there any new writing projects you are working on?

I’m working on something quite different. It’s historical, and inspired by my family, but this time I’m looking at my parents’ marriage. It’s a story about a Jewish girl in Connecticut in the 1960’s who watches her older sister fall in love with a young Indian Hindu man studying in America. My parents eloped in 1968 against their family’s wishes and I think about how brave they were and how much faith they put in their relationship. I’m happy to say they are celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary this year. I’m also toying with the idea of a follow-up to The Night Diary. I think it would be compelling to look at how Partition survivors rebuilt their lives.

TEXT Nidhi Verma