One of the leading contemporary artists in our country today, Atul Dodiya has built seminal oeuvre over the last three decades. A masterful storyteller, his complex compositions have often been a cross-weave of art history, politics, cinema, personal experiences and observations – disparate imageries coming together to manifest a searing, often cautionary commentary on society. One of his most iconic and recognisable works is of those created using the metal roller-shutters. As a response to the curfews during Bombay riots in the 1990s, Dodiya gravitated towards the shutter shop doors, which served as an ingenious ‘canvas’ – a medium now inextricably linked to his repertoire.

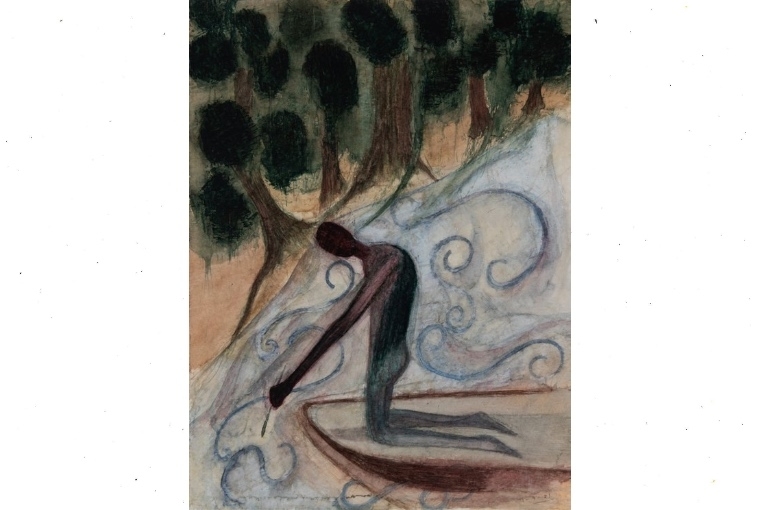

During the nationwide lockdown in the pandemic era, however, instead of picking another unconventional medium, Dodiya returned to the humble paper, pencil and watercolours. Across blank A3 size sheets, he drew faceless human silhouettes that appeared lost and alone. While Dodiya insists that these figures “are not doing anything”, what they convey in their quiet solitude is immense and profound. One of the untitled artworks features a mysterious, cloaked figure standing across an arid, brown landscape. Although scythe-less, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the Grim Reaper. Another painting depicts a nude female figure trapped in an oar-less boat, plunging downstream. These subtle and seemingly ordinary paintings are a reflection of our times, under- scoring the stoic nature of death and our rudderless existence in a pandemic-inflicted world.

Dodiya speaks about his new work, created over the last one-and-a-half years, that will be exhibited at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, this month.

Radhika Iyengar: Could you walk me through the work that is to be presented at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art?

Atul Dodiya: I will be showing a large body of work that I began producing 20th March 2020 onwards, when we learned about the seriousness of the pandemic — that, there would be a lockdown and people won’t be able to step out. No one had expected something like this. I hadn’t realised that I won’t be able to go to my studio and work there. Since we were confined to our homes, I decided to create small-scale watercolour works on paper. It so happened that I had an unfinished sketchbook that I had taken from the studio. So, I picked up the sketching pad and got down to work. Watercolour is a simple medium compared to oil painting. One could do small oil paintings too, but it’s a completely different process.

RI: During the lockdown, what was your artistic process?

AD: Apart from doing other things at home, I would paint from four in the afternoon till seven in the evening. I would sit in a corner of my room and just paint. I painted at least one painting a day. At times, if I was lucky, I would complete two works. I am also a great fan of Hindi film music – partic- ularly the Golden Era from late 40s to 60s. So, while painting, I would listen to Radio Ceylon on YouTube. One can listen to old songs on it and I was constantly listening to old Hindi music. In fact, one of my favourite singers is Mohammed Rafi – my day starts and ends with him. On each painting, I would write the date. Over time, I realised that I had produced over 300 paintings. I was thoroughly enjoying myself. I was engaged and involved.

RI: Three hundred paintings are a substantial number. Did art serve as a way for you to cope with what was happening in the world?

AD: I think what’s important is not how much I worked every day. What is important for me was the feeling the process evoked. It was hard to hear the news every day and learn how people were affected by the coronavirus. Every day there was news of people dying, of people being put on ventilators, of the lack of oxygen cylinders, of migrant workers moving from big cities back to their hometowns with their families, their children, many of them travelling by foot. All this news was overwhelming — knowing how painful the circumstances were for so many. So then, while painting, I would not try to forget what was happen- ing in the world, but it definitely helped me process it.

RI: Can the series exhibited at KNMA then, be interpreted as your visual diary of the pandemic?

AD: You could say that it is a diary in one sense, because literally, the dates are written on each painting. For someone like me, the lockdown was the best excuse to be a recluse. Since I could not work in my studio, I worked quietly in a corner of my home and I was left alone. That situation allowed me to create a certain kind of work. However, if you look more closely, nature dominates most of the work – sometimes the sky is dominating the frame, sometimes a river, sometimes trees or foliage and sometimes a figure is more prominent. I noticed that clouds, land, trees, river – these are elements that are constantly changing. Clouds, for example, are never still, nor are they ever the same. Even light changes as time goes by – from morning to evening. The lockdown period allowed me to observe and appreciate nature more.

RI: While painting this particular watercolour series, was there a theme that eventually emerged and tied it altogether?

AD: I’m a figurative painter, not an abstract artist. I would casually make a mark or draw a curve on the paper. It could suggest a hill, the back of a person or a stretched arm of a female figure. And I would proceed to complete that figure loosely in pencil and then paint it. After a few months, I noticed that I was painting mostly human figures in a landscape. That had been my subject all along. My earlier works include large bodies of work where I have painted Gandhi, then there are shutters, oil paintings and art history references. But here, in this work, there are no references of any artist, artwork, or artistic style. The paintings are of solitary figures looking at clouds, observing mountains or conversing with a tree: it’s just a pure moment captured between nature and human beings. The thing is, I find it difficult to explain what these paintings are trying to convey, but the process has helped me take a journey within. This work stems from a pure and innocent space. You see, during the lockdown, there was no commitment in terms of work pressure and it allowed me to be free. I was not expected to answer to anyone, so I was able to enjoy the artistic process and have fun. Otherwise, when one is painting, there are commitments, deadlines and exhibitions that need to be planned. But when you don’t have any commitment, then something magical happens. It was liberating.

I didn’t plan anything, rather, I allowed the work to guide me. I was like a log or leaf floating in a stream, allowing the current to take me wherever. The painting manifested the way it wanted to. The instructions were coming from the painting itself. Of course, I was the painter — but a certain stroke or a certain colour would guide me to the next step and I would just obey.

This article is an all exclusive from our March EZ. To read more such articles follow the link here.

Text Radhika Iyengar

Date 21-03-2022