‘A Discreet Exit Through Darkness reconstructs a mystery that has shaped Soumya Sankar Bose’s family for over five decades—the disappearance of his mother in 1969 and her unexplained return a few years later. Told through two interwoven narratives, the book unfolds from two perspectives: his grandfather, who relentlessly searched for his missing daughter, and his mother, who returned with no recollection of the years she was gone.

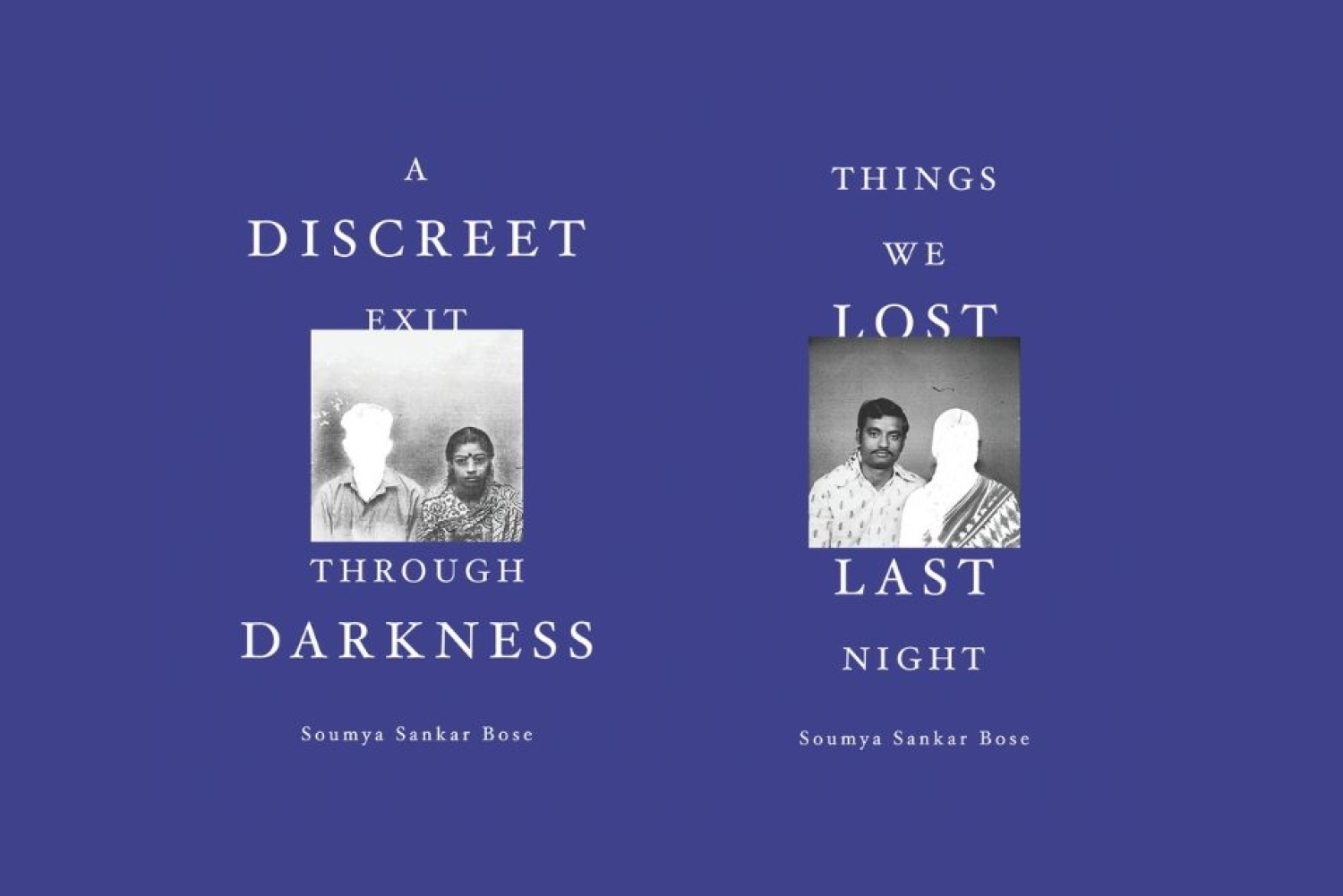

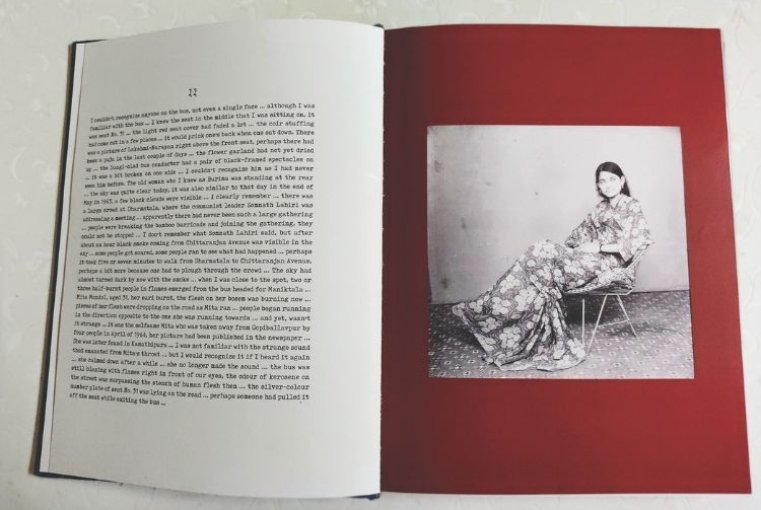

The first chapter is drawn from his grandfather’s diary, tracing a desperate journey through post-Partition Bengal, where political unrest, rumours of child trafficking, and fading superstitions shaped his pursuit of the truth. His writings, combined with archival research and Bose’s own reconstructions, piece together a father’s search in a time of uncertainty. While his entries are factual, they reveal the weight of his emotions—his hope, despair, and the silence that memory sometimes imposes on history.

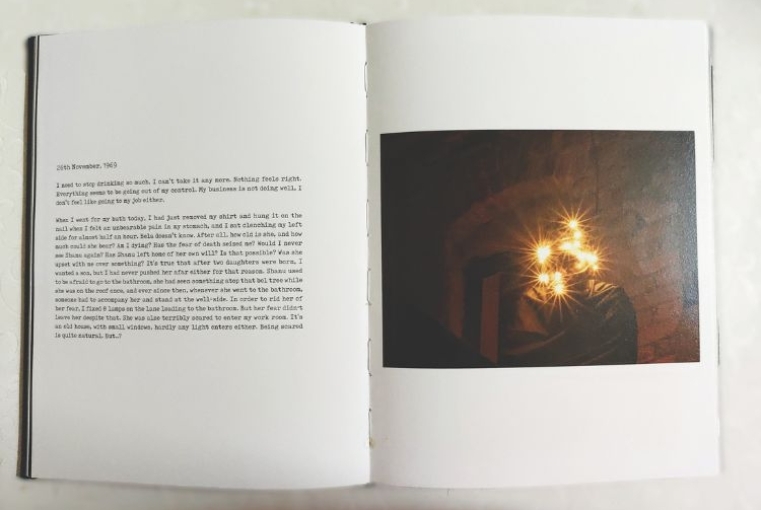

The other chapter, Things We Lost Last Night unfolds in his mother’s fragmented recollections, where memories and imagination intertwine. She remembers nothing of the years she was missing, but she carries the absence within her. Her struggle with prosopagnosia, or face blindness, further complicates her attempts to reclaim the past. Through conversations and journeys to places she might have been, Bose and his mother revisited these missing years—not to find definitive answers, but to understand how memory is preserved, reshaped, or lost entirely. This chapter moves between reality and myth, touching on the one-eyed woman who kidnapped her, the shadows of Maoist-Naxalite insurgency, and the sinking holy town of Joshimath.

This book is not just a family history; it is an attempt to understand how trauma lingers across generations, how personal grief intertwines with societal upheaval, and how memories—both real and imagined—shape the stories people tell themselves.’

Your art is so close to home and interwoven with your own reality – how did your growing up years shape the artist you are today?

My practice began organically, shaped by a condition I have called chronophobia—a fear of time passing. This pushed me to build an archive of my roots, family history, and the community I’ve known closely. In the process, I started uncovering regional, often undocumented stories—ones that matter deeply to certain communities but are rarely recognised more broadly.

Whether it’s my work on my mother’s disappearance or the decline of the performance art form Jatra, all my projects are interconnected and deeply rooted in where I come from. That’s been the core of my work for years.

Can you tell me a little about A Discreet Exit Through Darkness & Things We Lost Last Night? From what I’ve read, it sounds like such a piercingly beautiful book.

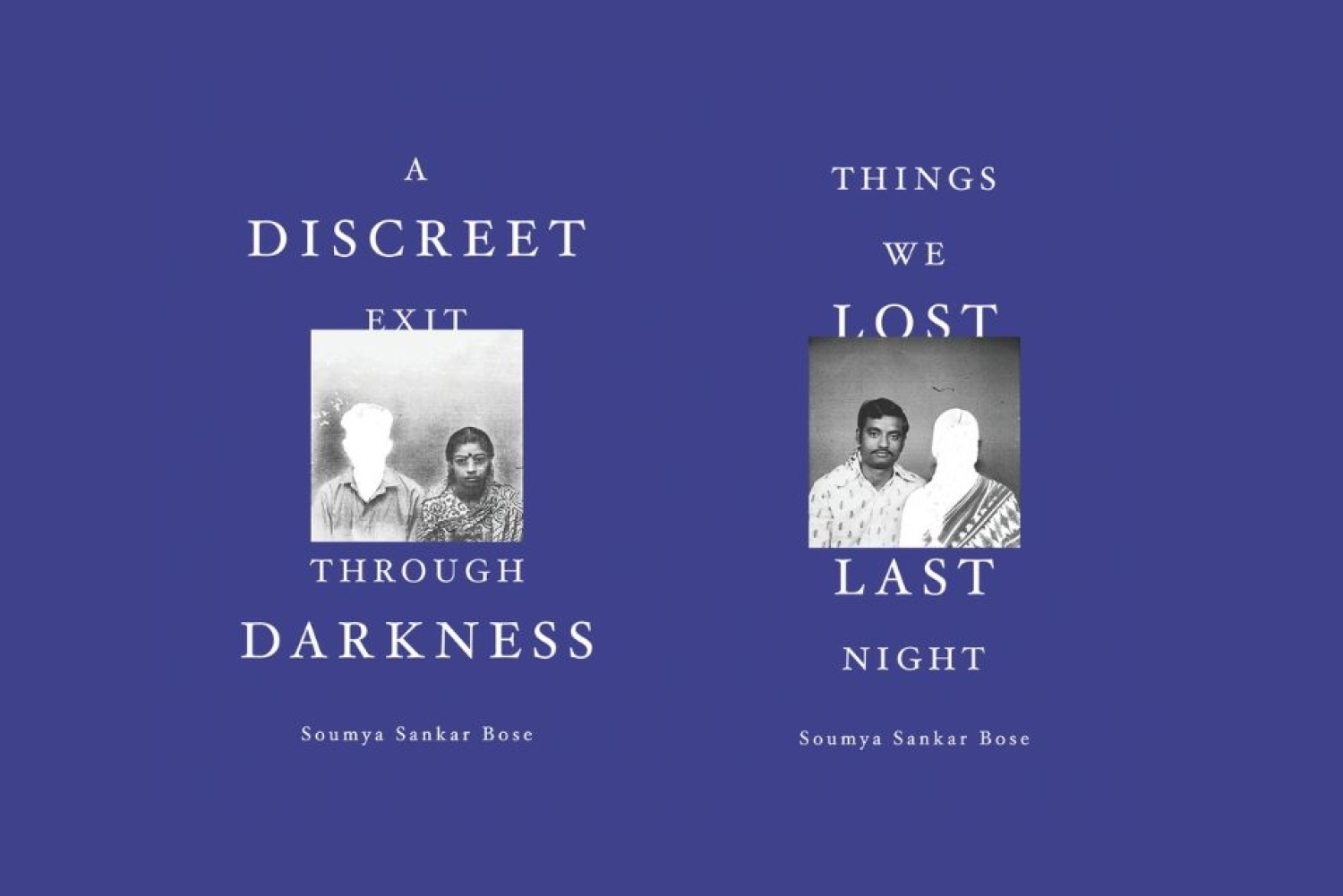

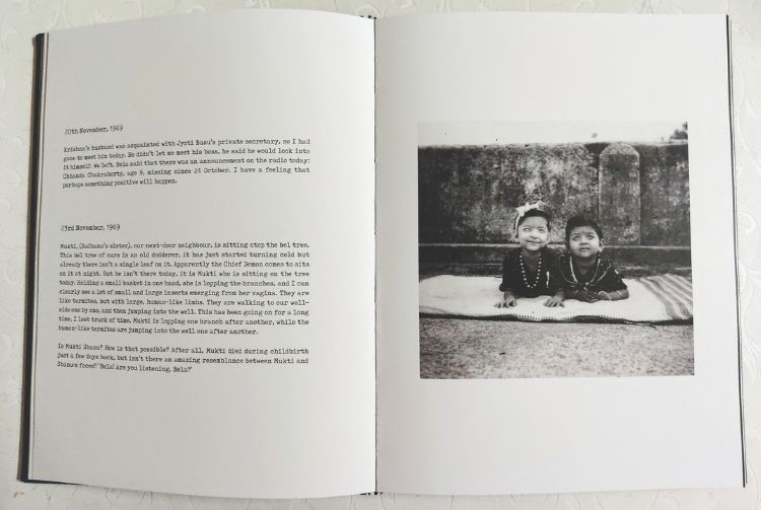

The book has two openings—there’s no back cover—so the reader can begin from either side. One chapter, A Discreet Exit Through Darkness, follows my grandfather’s search for my mother, who disappeared in 1969 at the age of nine. She returned a few years later, but my grandfather died during the search. This part traces his investigation and emotional journey.

The other chapter, Things We Lost Last Night, tells the story from my mother’s perspective. Her memories from that period are fragmented, so the narrative is built from her diary entries, oral accounts I gathered and archival material from old newspapers. Together, the two chapters blend personal histories with the larger socio-political landscape of 1960s and ’70s West Bengal—a time of deep unrest and transformation.

How did you decide on the structure?

I’ve been working on this project for the past five years. A lot of that time went into shaping the narrative from two distinct perspectives. The book isn’t just about photographs—text plays an equally vital role. Many of the images were originally taken by my grandfather and later recovered from our family archive; I added my own photographs as well. The writing is shared between my mother and me.

I wanted the structure to reflect the fragmented nature of memory. Since the event happened nearly fifty years ago and my grandfather is no longer alive, much of what he went through remains uncertain. That made multiple perspectives essential. During my research, I encountered different versions of the same story, told by people who remembered it in their own way.

This led to the idea of a two-sided opening—inviting the reader to enter from either direction. While the incident, dates, and people remain constant, the emotional terrain shifts depending on whose voice you follow.

In A Discreet Exit Through Darkness & Things We Lost Last Night, how did you manage to keep emotions aside—or did the emotions help in telling the story?

With Things We Lost Last Night and A Discreet Exit Through Darkness, the process was deeply personal but I didn’t approach it as just my mother’s story. I interviewed many people, including those who had gone missing from Midnapur around the same time. I also went through newspapers from that era and explored broader histories—trafficking, the Naxalite movement and the political climate of the 1960s and ’70s.

The narrative stretches across three decades, starting in the 1940s when my grandfather was growing up, and continuing through to the early 1970s. This wider historical lens helped me maintain emotional distance. While the emotions were real and present, grounding the project in research and multiple voices allowed me to tell the story with clarity and perspective.

As an artist and storyteller, you tell visual stories steeped in history, memory, loss and identity. What inspires you to tell these stories and what stories resonate with you?

I’m drawn to the way history shifts over time and how people revisit and reshape their memories. My work often begins with oral history, which is fluid by nature—it changes as we change. The way I might interpret an incident in my 20s could be very different from how I see it in my 30s or 40s, because the world around me—politics, culture, personal priorities—is also constantly evolving.

What inspires me is this ongoing transformation of memory and meaning. I often begin with something personal, then expand through research and conversations, letting the story grow organically. That process—slow, layered and reflective—is what keeps me connected to the themes I explore.

Do you need to feel to create?

There’s no fixed answer to that. Each moment is different from the other. Sometimes I feel deeply connected to a story, a character, or a memory—and that emotional link feels essential. Other times, I work with more distance. That’s part of the practice: it shifts with time and experience.

These emotional fluctuations are natural and beautiful. Some days the work feels heavy and consuming; on others, it flows easily. If you asked me this question a few weeks from now, my answer might be different. That’s just how it is—and I’ve learned to embrace that.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra

Dat 18-07-25