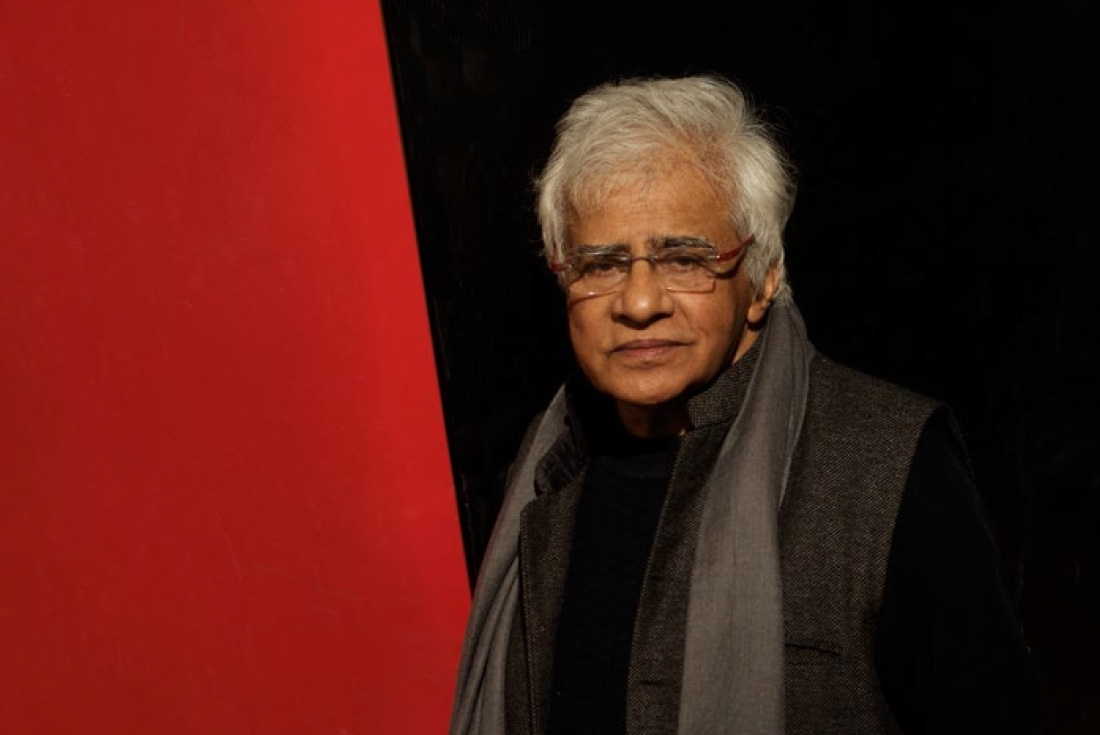

Photography Sharad Shrivastava

Photography Sharad Shrivastava

You were one of the first artists from your contemporaries to branch out into conceptual art, photography, video art, and installation art. What intrigued you to explore these mediums?

I am a big believer in time and moment. We are talking about the early 90s – collapse of the Soviet Union, a new economic order, television etc – there were enormous changes taking place both nationally and globally. I had travelled to New York and I found that the nature of art practice in our country was very restricted to painting alone. Even in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America there were radical changes in art and I felt that the time had come. It was the moment when one could shift, it was in the air and I did. In a broad sense that was the starting point.

What kind of reaction did you receive?

My paintings sold well because I came with a reputation but when I did a series after the Gulf War where I used engine oil and charcoal, people joked and wondered if it would last but that was still in the tradition of graphic and it still sold. The next show Collaboration/ Combine in which I made sculptural objects brought in very different elements, I worked with architects and I started using photography. In fact, I made a six-foot stone column weighing 6000 kilos but on the face of it were photographs. This piece was a curatorial show of unknown photographers who today are some of India’s top photographers, including the likes of Dayanita Singh, Ram Rahman and Ketaki Sheth. It was the beginning of an attempt to strike a dialogue with people in other disciplines, to question the notion of the single author, of participation and critiquing that uniqueness that only a hand can produce. Suddenly in art, things and objects in the world that exist could be included and employed, which is actually an old strategy coming in from the West. I felt that there were all these things that were being kept away and in our home ground we were more conservative.

What sparks your creativity?

I went to study in Baroda and in the 60s it was a very radical and happening place that encouraged new ideas. Then, I went to study in London again in the 60s and that was also happening on a global level. Both these locations informed me. Politics, moving towards leftist thought and Marxist positions, critical radicality has always been part of my blood stream. To question the dominant in whatever artistic way one does and to always continuously position oneself from what has become ossified or static in some way. And that sparks my creativity till date.

You are, of course, no longer a stranger to art. I wonder if artists with half a century of practice still feel alien sometimes, given the constantly changing landscape of art.

By and large, because of the nature of my practice, from the very start as a student of aesthetics both in India as well as in London, I was constantly questioning the premise of being there. It was the end of the 60s that kind of dramatically changed the nature of my paintings. And I am a great believer in responding to the environment, to changed aesthetic, even a new political situation. I have always constructed my work in a non-linear manner, moving from aesthetic, the visual, to a very different medium…as well as in how the content and context reflects. Whereas most artists have a style, a stand, there is no consistency to my work at that level. Then the way that this argument keeps representing itself is in the collage nature of my work that keeps on making different propositions, and hopefully some sort of a pattern emerges from this.

Your thoughts on learning and unlearning as an artist.

I’m constantly learning and unlearning. Almost simultaneously. I start with not much of a history of the aesthetic or content that I employ, I kind of take a leap into it. So there is an element of spontaneity. I want to refer to the topical/political—something that is around me or I may have experienced. There is a notion that once you’ve got the style and you are a Souza or a Raza you know where to put the line in the pattern, but I’m consciously stepping aside or constantly repositioning.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra and Soumya Mukerji