Let's Get Silly

Khushnaz Lala never meant to grow up. Adulthood happened to her by accident. Challenged by the real, practical and ever-so-boring world, she reached out to her sketchbooks to hold on to the child within her. An illustrator and writer based out of Bangalore, Lala found inspiration in the world around her. The beauty of her work lies in its sheer simplicity. Her primarily text-based artworks are a humorous and honest depiction of her observations, frustrations, late night musings and loopy jokes. When she decided to string together these random thoughts and scribbles, she ended up with three books that were launched at Bookaroo Children’s Literature Festival late last year — I’m With Silly, This is a Very Silly Book and Dear Left Sock and Other Letters. Fondly labelled ‘child-friendly books for adults’, these picture books for young minds double up as a reminder for grown-ups to tap into their lighter side. Delightfully irreverent and witty, these artworks are born out of Lala’s conversations with herself, and at their core lies a very powerful message — each of us is different, and it is important to celebrate what makes us unique.

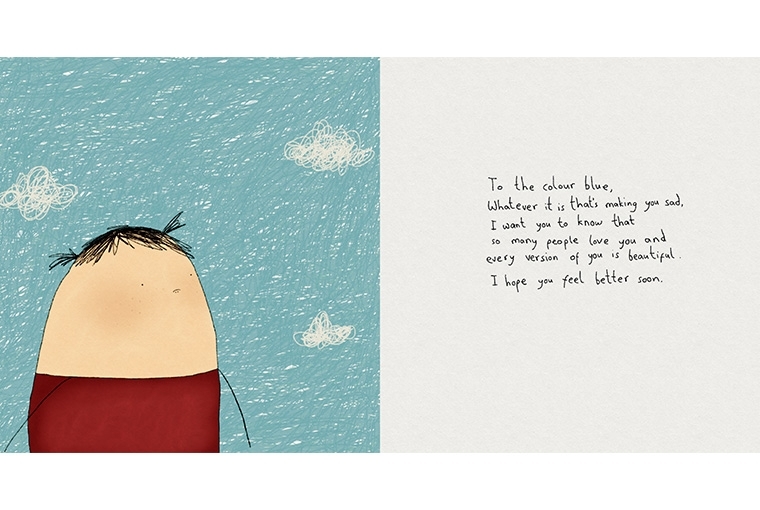

‘The books were written as college assignments, but once I decided to get them published, I felt the responsibility to really analyse what I had written and what I was saying. I realised that I’d made these characters that were ‘freaks’ maybe because that’s what I’d felt like, and was called when I was a kid. But I wanted their weirdness to be celebrated. And so I reworked the books as a message to my younger self. I wanted to tell her to embrace her freakishness, that she wasn’t made ‘wrong’, because there isn’t a ‘right’ in the first place,’ says Lala. With letters to coleslaw, the colour blue, a missing sock and other very silly things, Lala puts together snippets of thoughts that remind us that silliness is not a thing to be lost as we grow up. ‘I guess why we equate silliness with children in the first place is because we look at childhood as this very romanticised age of pure wonder and unbiased observation. I think what happens eventually is that we take our observations and start forming judgements, and then become conscious of ourselves being observed and judged by someone else. We’re caught in this trap of watching ourselves being watched. And so we’ve made up these rules about how we should act and speak and be, and it’s scary to stray from them because it leaves you vulnerable. But I think that’s exactly why not caring about it is really brave, and the important thing to teach ourselves as we grow up,’ she says.

“The books were written as college assignments, but once I decided to get them published, I felt the responsibility to really analyse what I had written and what I was saying. I realised that I’d made these characters that were ‘freaks’ maybe because that’s what I’d felt like, and was called when I was a kid. But I wanted their weirdness to be celebrated. And so I reworked the books as a message to my younger self. I wanted to tell her to embrace her freakishness, that she wasn’t made ‘wrong’, because there isn’t a ‘right’ in the first place.”

Lala’s romance with the written word began quite early. She was all of nine when she started having trouble in school and began writing poems to deal with it. As she traces her journey as an illustrator and writer, she finds a constant influence that never left her side — her family. ‘Seeing that these poems were a way for me to not just express myself, but also find humour in those situations, my parents were extremely encouraging like they have for all my hobbies. One summer, my dad had bought me two Shel Silverstein books and some other amazing books on poetry and writing, and I’d spend all my time with them. I think their shared ardour to push me on to explore my creative side is what chiselled my interest in writing,’ says Lala. But as she grew up and writing assignments became all about getting the perfect grade, she felt her passion slipping through her fingers. ‘I used to write a lot as a kid, but then I started hating it once it became all about scoring marks. During my undergraduate course, I got bored with it and told my professors that the language and form I was expected to use was just dull and didn’t make sense with how I wanted to communicate my thoughts. They encouraged me to ask bigger questions about conventional writing styles. I started to do that through these weird little picture books that I’d keep making as assignments. Once I found my ‘voice’, I started to really enjoy writing again,’ she sums up.

But it was during a course in Contemporary Art Practices that she learned to filter her influences, and use her emotions to carve out her body of work. ‘I feel the most valuable thing I learned was to get angry, instead of being upset with myself. I started channelling my angst into my work. It then bled into my everyday life and my sketchbook, like a journal. I found it empowering to think of my thoughts as art. It didn’t have to dress up and get pretty for anyone else.’ Soon after, she put together her first solo show titled F.ART with her text-based illustrative work that was a sardonic commentary on art within the gallery space, and followed it up with a TEDx talk titled ‘I am God but I am also Garbage: how to con your way through adulthood while eating Cheetos in your underpants.’

Her creative process translates simultaneously in text and in illustrations. She usually finds the ideas lurking in some corner of her mind, and they unfurl together in thoughts and images. She couples her musings with freehand illustrations. ‘I think ‘childlike’ has more of a positive connotation and is a very nostalgic way of looking back at childhood as this magical playtime full of possibility. To be ‘childish’ is slightly more negative, to mean immature, but to me actually means to be less contrived and more instinctive. But I still see value in both, and they each serve different roles depending on what needs to be said. I think my books are playful and whimsical, but they have a very adult observation to them. My artwork on the other hand is stupid and crude, but still spontaneous and honest.’ At the heart of the nuances that largely shape her work lies a very special relationship — one that reminds her that age, really, is just a number.

“I feel the most valuable thing I learned was to get angry, instead of being upset with myself. I started channelling my angst into my work. It then bled into my everyday life and my sketchbook, like a journal. I found it empowering to think of my thoughts as art. It didn’t have to dress up and get pretty for anyone else.”

‘A lot of people tend to infantilise kids but I try not to judge a person’s intelligence and capabilities based on their age. My best friend [whom I wrote a lot of my books with] happens to be a nine-year-old; and we discuss politics and gender and sexuality and philosophy, but we also make fart jokes and try to go through a day with our fingers taped up like T-Rex hands. It’s like any other friendship I’ve had, only I try not to swear in front of him. It’s really not hard to balance these perceived worlds once we allow ourselves to move along our own spectrum of maturity and see that it has very little to do with age.’

Lala writes not for others but for herself. Much like a child’s drawing stuck to the fridge with a magnet, her words hint at an enviable simplicity that we lose somewhere amidst the hullabaloo of growing up. She finds her zen that way, and in the process, urges us to do the same. Talking of the year ahead, she says, ‘I could get super successful and take over the world, or more likely, get overwhelmed by the littlest thing, have a breakdown, swear off society and move to Borneo to live with monkeys.’

Text Ritupriya Basu