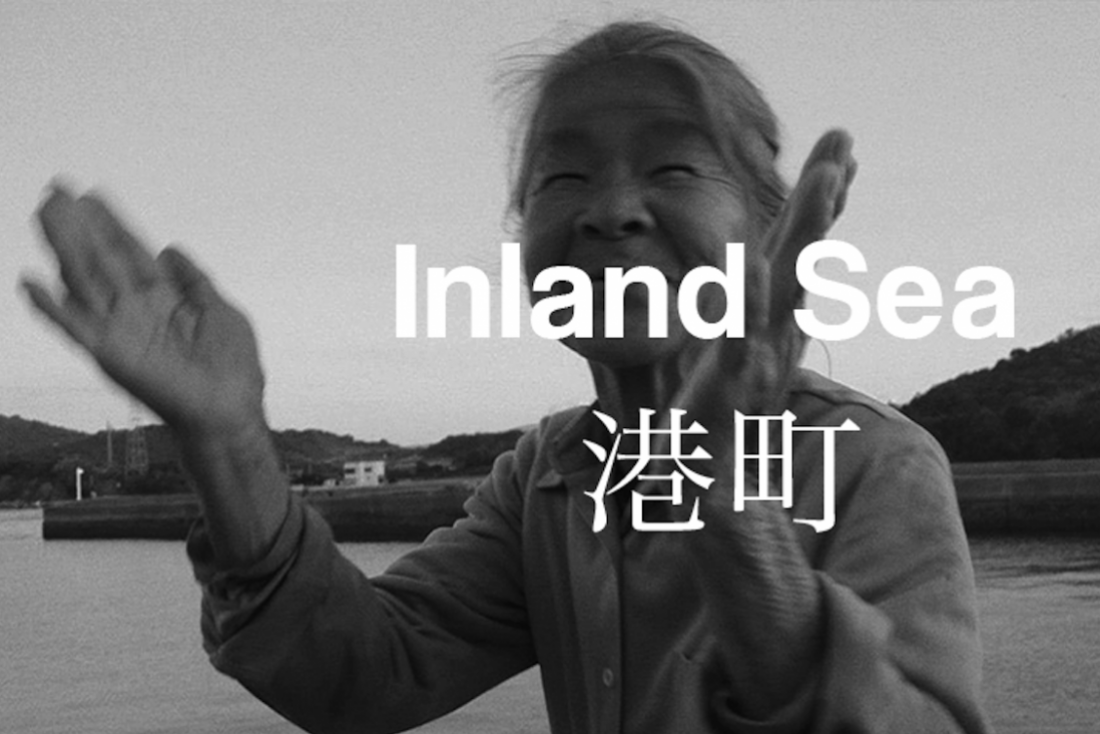

Extremely long takes, character driven and subtly captivating are just few words from a long list of beautiful adjectives that describe the observational filmmaking of Kazuhiro Soda. At this year’s Dharamshala International Film Festival, Kazuhiro Soda’s Inland Sea was screened and Soda himself was present to take a masterclass on his unique brand of cinema. Since my love for Japanese storytelling in any form is endless, needless to say, I was thoroughly inspired by Soda’s vision and words. Before the screening of his 7th Observational film called Inland Sea (Minatomachi), Soda shared with us his ten commandments of filmmaking: ‘no research, no meeting the subjects beforehand, no scripts, roll the camera yourself, shoot for as long as possible, cover small areas deeply, do not set up a theme or goal before editing, no narration or superimposed titles or music, use long takes and pay for the production yourself’. A simple way to describe Soda’s commandments would be to simply add a no to all the commandments that filmmaking students are taught! After he left us with his commandments lingering in everyone’s mind, the film became an object of much intrigue and as his movie came alive on screen, so did his observational filmmaking.

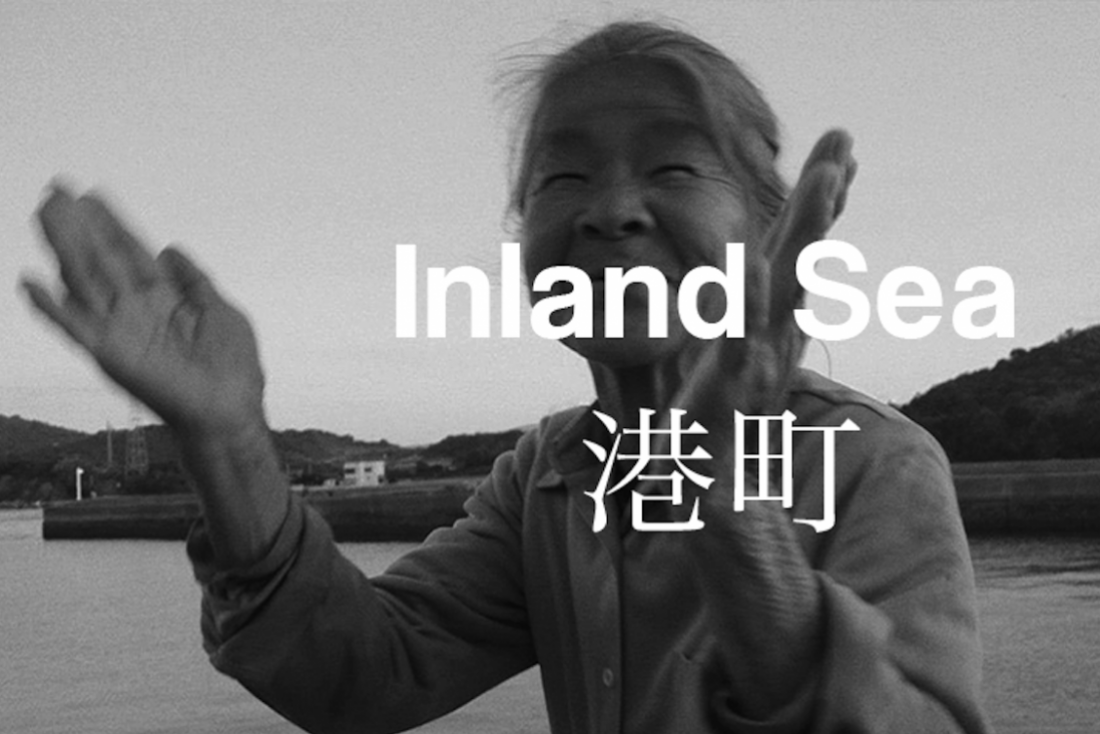

Inland Sea captures the twilight days of a small village named Ushimado on the shore of Japan’s beautiful Seto Inland Sea. Soda takes us from subject to subject, character to character, in his documentary as he himself discovers them and he and his wife (Kiyoko Kashiwagi who has also produced the film) speak to them further about their lives. We are first acquainted with Wai chan, one of the oldest residents of Ushimado and also one of the last fishermen of the town. Wai chan assumes a larger part of Soda’s cinematic space. We see him fixing his own fishing net, telling us how a cat bit his trousers because he smells like fish, how fishing nets now cost more than fishermen actually make by catching and selling fish, his daughter who is doing very well for herself working for a major company and finally, in an extremely long take, Soda takes us through Wai chan’s process of catching fish. From Wai chan going into the sea just before dawn to catch his fish and keep them alive as they fetch him more money when they are alive to him taking the fish to the vendors who place their bids on the freshly caught produce, the line between cinema and reality almost disappears. Since Soda’s takes are so long and the footage is barely edited, one views everything in real time. Its almost as if you can extend your hand forward and touch and feel what you’re seeing.

Wai chan in a film still

From Wai chan, Soda then moves onto his other subjects that include the owner of the fish shop with whom Soda also goes around town and she sells fish door to door. From the shop, the director then comes across a couple who take the offal from the shop and cook it for the many cats around their house and feed them. Soda absolutely loves cats and one can also see them on his business card as well! As he is speaking to couple, an elderly woman walks by wearing a jacket that says dog-catcher at the back. Naturally Soda is much too intrigued by her and decides to follow her. Here we come across a women who is maintaining and decorating not just her own ancestors’ graves, but also the graves around them, that have been abandoned. Finally, a larger chunk of the film at then end, focuses on an elderly woman named Kumi san. Kumi san is that one person in a small town that knows all the local gossip, knows every nook and corner of the town like the back of her hand and absolutely loves to chat and share all the information she knows with others.

After one point, Kumi san’s presence is so dominant in the film that she starts directing Soda to shoot footage of things around them. Almost nearing the climax, Kumi san takes both Soda and his wife atop a hill to show them a building that used to be a school but is now a hospital. Here she recounts the story of how her son was snatched away from her and is now being kept in a facility where he is being treated really poorly. There is music playing in the distance somewhere which is a song that alert everyone of the time of the day as Kumi san speaks about her life and Soda treats this footage with utmost respect. When asked if he actually went to check after Kumi san’s son, Soda said that, ‘I did not want to do it. What she told me is her reality and I respect that. I did not want pry further than that.’ As the film nears its end, I found it very interesting that even though what is being shown is a town that is almost on its last legs, one does not feel any sense of gloom. Even though the these are the twilight days of Ushimado and its residents, the light is very much alive. The close knit fishing town is still filled with life and love, even if it inevitably will lose both. While Soda had shot all his footage in colour, during his editing process he turned the film completely black and white. ‘It has an effect of putting another layer of fiction, which fits the film perfectly,’ he told us when asked about his editorial decision.

The astounding humanism and simplicity of the film is the actual winner. Even though the film is named Inland Sea, the sea itself ends up only in a few shots in between long takes and becomes a topological canvas on which the lives of the residents of Ushimado comes alive. Modernism, globalisation and capitalism has left this city deserted and one might make the mistake of being reductive and calling Inland Sea an elegy for Ushimado and its bygone days, but the film is truly a celebration of life. Its subjects include people who are in their ninth decade of life and they may be hard of hearing and stooped, but they still come across and lively people. Unfortunately, Kumi san passed away while Soda was still editing the film which makes the ending perhaps even more powerful for Soda. From the neighbourhood cat called Shiro, who has become so domesticated that he rolls over when the people ask him to, to the last shot of the film after credits that shows the sea in its actual colour, Soda’s movie is a beautiful rendition of his observation of the Ushimado city and its twilight days.

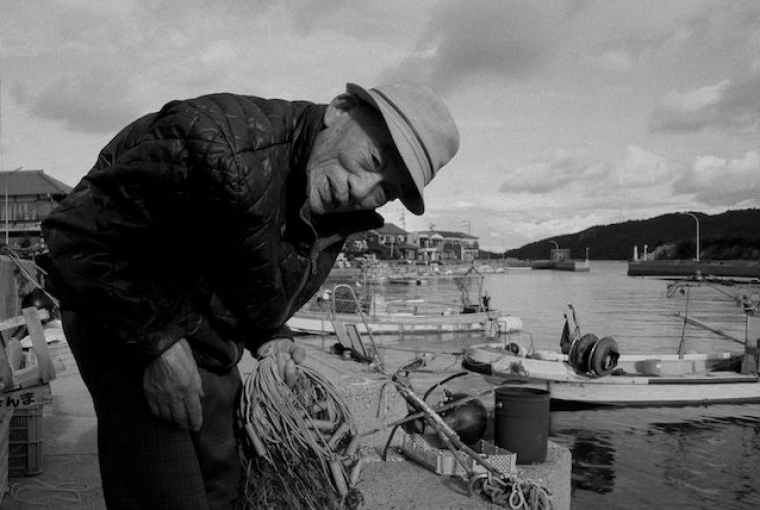

Kazuhiro Soda