Author's photo by Jillian Edelstein

Author's photo by Jillian Edelstein

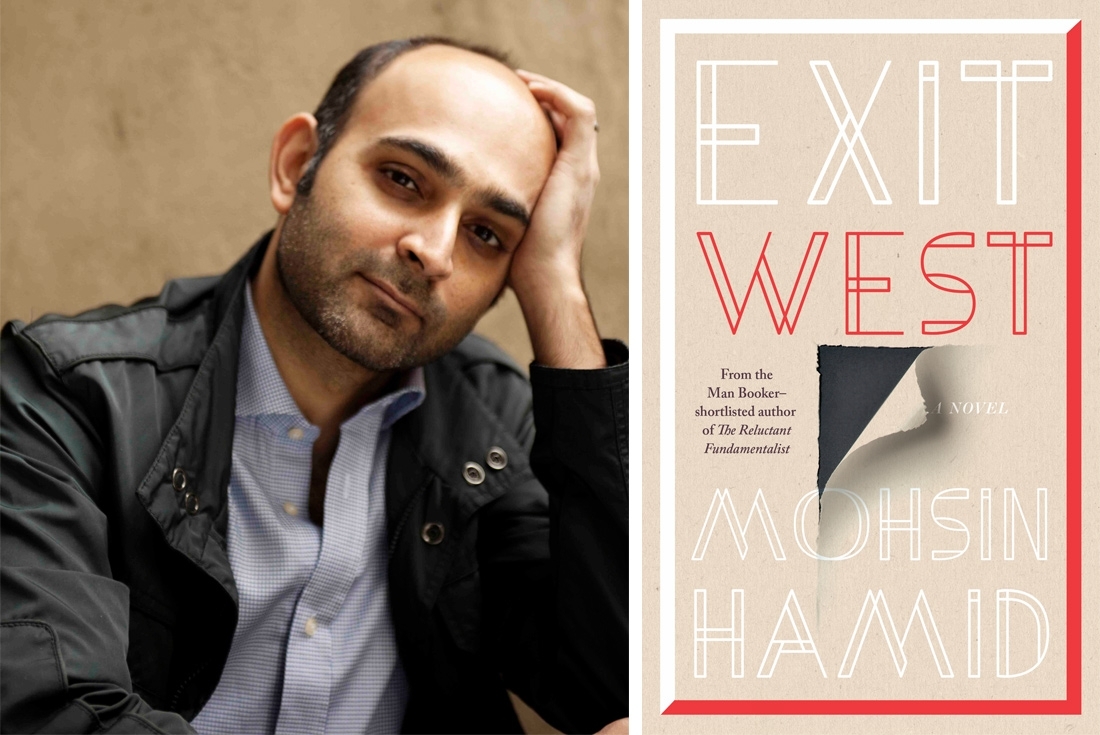

Stories and childhood. Childhood and stories. One becomes unthinkable without the other, those two guardians of imagination. And then, a terrible thing happens. We grow up. We wear out. The words we read go from wondrous and fantastical and full of possibility to precise and factual and suitable, and even the best of writers start to doubt themselves. Like award-winning Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid, who even after writing a masterpiece such as The Reluctant Fundamentalist, felt a loss of inspiration till reading to his children made him believe again in the unparalleled power of storytelling. And thus was born Exit West, his latest novel, which is a tale of two lovers—Saeed and Nadia—who embody the migration of the human experience, much like the author himself.

What is your first memory of writing?

I’m not sure of my first memory of writing, but I can remember the first book I sat to write. I was probably about seven or eight years old and I was in California and I had seen Star Wars, the movie. My first book was in a school notebook—I wrote a kind of galactic space opera with stick figure illustrations of spaceships, battles and that stuff.

How has your craft evolved over the years?

I began my novel, The Moth Smoke, in early 1993. So it’s been about 24 years and I think much of the first decade was spent figuring out just how to write a novel and trying many different things. In fact, much of the second decade was spent the same way. The Reluctant Fundamentalist took seven years and The Moth Smoke took seven years and in both cases, I was just trying to figure how to write those books! My third novel, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, took six years but still had many failed attempts. But my most recent novel took four years, and the first real attempt I made formally in terms of how it was structured, was quite close to the final version. I don’t know if this was just a coincidence by luck, or if I’d learnt how to write more over the decade, but this book certainly felt a bit different in terms of how it was created. May be because I’d become a father and I read to my children every night—I’d changed. And the simplest idea of being a storyteller has become more the heart of my craft and it certainly shaped my process of this book.

What inspired Exit West?

I’ve been moving around my whole life. I’ve lived in California, in NY, in London, Lahore on three different occasions, even today, and so I’m a migrant at the very fundamental level. And I’ve been feeling this migrant sentiment growing and I wanted to write in reaction to that, to write about the universality of migration of the human experience and the wonderful fertility and beauty that migration can bring. That really was at the root of this level.

What is your definition of an ‘outsider’ and that of ‘belonging’, two important words evoked from the pages, and two of the most misused words in the new world order?

I think that actually, everyone is an outsider. It depends on how honest we are going to be with ourselves. In Pakistan, you’d say I’m not an outsider. But also, you’d say I’m very substantially shaped by my experiences in America and in Britain. I have views on secularism, all gay rights, feminism, racial equality, artistic freedom and those views makes me in many instances an outsider in Pakistan. Similarly in America where although I went to Harvard and Princeton and I worked in corporate NY city and therefore I should be very much an insider, by virtue of having a Muslim name and brown skin and having my particular politics and artistic viewpoint, I sound like an outsider there, too.

I think everybody has in them elements of an outsider. It could be that you’re the only liberal person in a conservative family. Or the only gay person in the family… or the only person who wants to be a writer in a family full of engineers and doctors…because we have so many different identities, some of our identities will always be an outsider. The question becomes, do we embrace all of our identities as individuals or do we just pick one or two? And when we talk about belonging, if everybody is an outsider there must be the potential for everyone to find belonging. I don’t believe that someone born in Delhi or Lahore or Karaka or Mogadishu should have different fundamental rights from those born in NY, London Paris. If we can accept the multiplicity of our individual identities, we can also extend belonging to everyone.

The past and the present meet throughout the story…

I think everything is transient. Everything is contingent and temporary and brief. And we get into trouble when we imagine this is not how it actually is. That things won’t change, that they will remain the same forever. I think that denial of transience, of temporariness results in all sorts of misconceptions and political disasters. For me the real interesting question is, how do we find beauty and hope and optimism and love while also accepting that things are not permanent? That’s where this novel goes.

What was your biggest challenge while writing this book?

I think the biggest challenge was to re-embrace the simplicity of what storytelling can do. Writing is a discipline with its moments of doubt. But for me, with this novel, by reading stories to my children and believing in the incredible power that those stories have over them, the biggest challenge was remembering at the basic level how much storytelling can do. That stories are not meaningless but actually essential.

Take me behind your creative process.

Each book has been different. Normally the way my novels are written is that I spend several years writing a draft, throwing them away. And sometimes, those two-three drafts have not one sentence in common with the final book, they are just experimentations. But with this novel strangely enough, the initial and final drafts were very closely related. My daily schedule is just sitting in office and waiting for the writing to happen, I sit at my desk in the morning and write until lunch and sometimes I sit there and nothing happens, I sit there with fewer words than I began because I’ve been revising and deleting.

How do you observe the diaspora changing through the decades as you create narratives around them?

The notion of a diaspora has to be revisited. So if you are a Punjabi or a Jain sitting in Toronto we’d say you’re part of a diaspora. But what if you’re a French man sitting in Quebec? Are you a diaspora? What about someone from NY living in San Francisco? Are you a part of a diaspora? I think the notion of diaspora implies that there is some homeland that you are separate from. But in our modern world, everybody seems to be part of a diaspora. I think the experience of living in a big city in Pakistan or India or anywhere is in itself a diasporic experience. And so I don’t think of the diaspora as one uniform thing, I think there are individuals who make it up and the stories of those individuals are different from one other.

What is next?

I don’t know, my daughter tells me I need to write a children’s book. And she’s very forceful. So I think I should probably do that!

Text Soumya Mukerji