‘Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there./ When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.’

I remember coming across these beautiful lines from Jalal-ud-din Rumi’s poem ‘A Great Wagon’ during the early days of the quarantine. I still go back to that memory and take solace in the calm these lines instilled in me. Our world has been plunged into chaos and the list of things that it is suffering from, aside from a global pandemic, is getting longer everyday. In such times of bleakness, one’s existence often feels futile. To overcome such feelings of hopelessness, I’ve often turned to Rumi’s words for comfort.

While Rumi’s poetry was composed during the thirteenth century, it somehow resounds with millions even today. More and more of his poetry is being translated, read and taught for its deep spirituality and buoyant wisdom. Farrukh Dhondy, a well known writer, playwright and screenwriter, had worked on a new translation of Rumi’s poetry a few years ago, which brought out the beauty and sensibility of the verses while carefully keeping intact their religious context. He has now worked on a new collection of poems, which will be released this month. With selections from Rumi's masterpieces the Masnavi and Diwan-e-Shams, as well as his ghazals, Rumi: A New Collection is a poetry lover's treasure-trove.

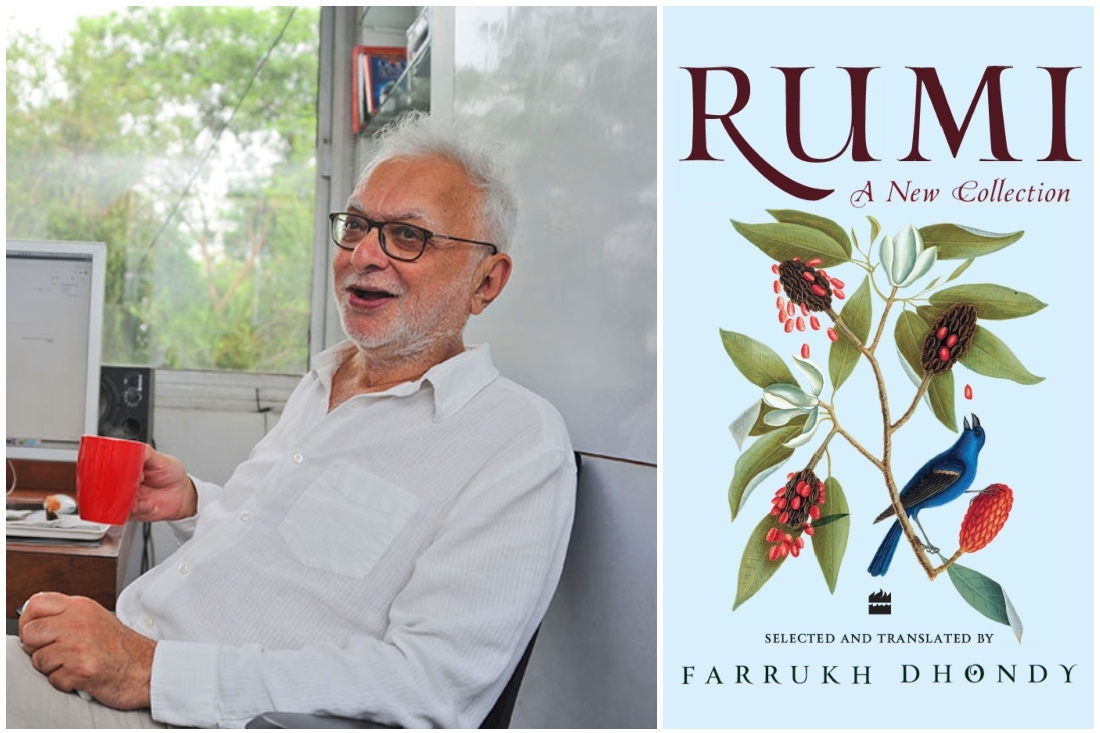

We connected with Farrukh Dhondy to know more about the new book, his relationship with Rumi and the role of literature during the pandemic and beyond.

How were you led towards literature?

As a young man I was rather clumsy at games — tripping over my hockey stick, being apprehensive of the fast-bowled ball, and never sure why I was in the boxing ring. Let’s face it: writers would prefer to be on the payroll of Manchester United than come fifth on the best-seller list and receive a parchi saying you still haven’t earned your advance. However, one works with one’s talents and if you find people listening to your stories and if you are fascinated by modes of expression, you might conceive of being a writer. I did.

After all these years, how would you describe your relationship with the written word as?

St. John says, ‘In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God.’ The whole endeavour of the writer is to wrest the correct, appropriate and simplest words (note the plural) from God and sculpt sentences with it. The greatest satisfaction is describing things, conversations, events, scenes, people, seasons, things as they are and making the description fresh. The greater satisfaction is when a reader tells you you’ve done it well and a subsidiary satisfaction is seeing your written words turned, through the talents and art of directors and actors, into filmed scenes.

How was the book, Rumi: A New Collection conceived?

I was on a plane to Australia from Mumbai and my friend Soli Irani gave me a book of Rumi translations in English to read on the ride. I tried. The ‘poems’ were just chopped prose without rhyme, rhythm or reason, full of idiotic mixed metaphors and pretentious new-world obscurantism. I threw the book away and when I returned to my mamaji’s flat in Mumbai, I said I thought Rumi’s poems were rubbish. He could have slapped me, but instead went on to recite verses of Rumi he knew by heart. They were rhythmic, they rhymed, they were in iambic pentameter and their word-music was enchanting. I got my mamaji to translate and began turning the first few poems that very night into English, attempting to maintain the rhythm, the rhyme, the meaning and the music.

How do you make sure that a poem is not lost but found in translation?

It was the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko who said something to the effect that translations are like lovers – if they are handsome they are not faithful, if they are faithful they are not handsome. (He may have used the Russian word for ‘beautiful’ — but one must be very careful these days!). So a loss in translation would be betrayal of the meaning or music of Rumi’s verses, the first one being Sufi belief and the second the superb use of the universal instruments of poesy. Which is why I have attempted to be rhythmic, to use rhyme as flexibly as the different grammar and syntax of English allows, and to convey the Sufi mystical message without obscurant mystification to flatter the reader into believing that he or she has reached some state of higher consciousness.

What was your curatorial process like behind the new anthology?

I used the original translations into faltering English prose, Urdu and footnotes about context, supplied to me by my Persian-reading friends. They, mainly the late Firdous Ali, chose the poems from the labyrinthine work of Rumi and from this endless selection I chose the ones that made most sense or felt most compelling to me.

This is your second translation book of Rumi’s poetry. What kind of a relationship do you personally share with the poet and the poetry?

I am not a Sufi. I am not even remotely religious, but am addicted to the expression of all poetry and to the music of, say, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. The Parables of Rumi, the stories through which Sufism is conveyed are unique and fascinating. I’ll never pretend that they are for me enlightening or that they take me on some journey of the spirit — mine might have escaped a long time ago — but I approach this ocean of Rumi’s work with the respect of a person learning to swim.

The world has been thrust into a rather baffling and challenging time. What do you think the role of literature should be in our current situation?

The role of literature won’t change because we are faced with a global plague and also, very recently and at welcome last, with a very wide-spread international demand for an end to discrimination on the basis of race, religion or colour. No doubt some stories and some rhetoric will be inspired by both these but writing, 'literature’ when it is worthy of the word, will continue to explore the limits of human imagination. Words will continue in myriad forms and genres, to capture, to represent and transmit the chagrin and the pity.

How have you been coping with the pandemic and what will be the new normal for you post it?

I am told by the British government and a daily hail-storm of statistics that Covid-19 comes to me as a flame to a moth — or was it the other way round? I’ve been scribbling away on the computer and in note-books. Finished a book of Hafiz translations commissioned by the same publisher, Harper Collins, and have spent my time bashing the keys and going through a Parsi cook book, and then getting recipes for Shami Kebab and naan from the internet. No crosswords, no Sudoku, no games — but dusted-off unread books which have been waiting on the shelves for a pandemic to keep me home.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

My autobiography commissioned by Amazon, which is drafted and sent, and then a novel which I am thinking of publishing under the name Kamal Kukuldash — but shall have to see what my agent says about her being able to sell it even with my name attached.

Text Nidhi Verma