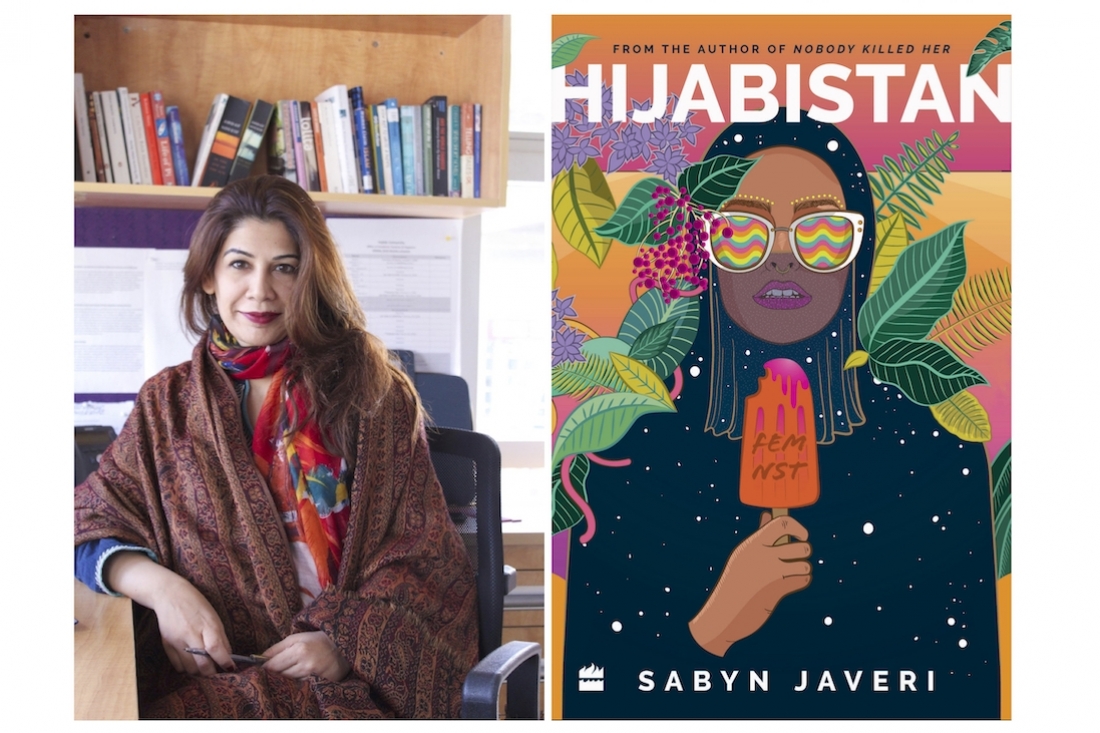

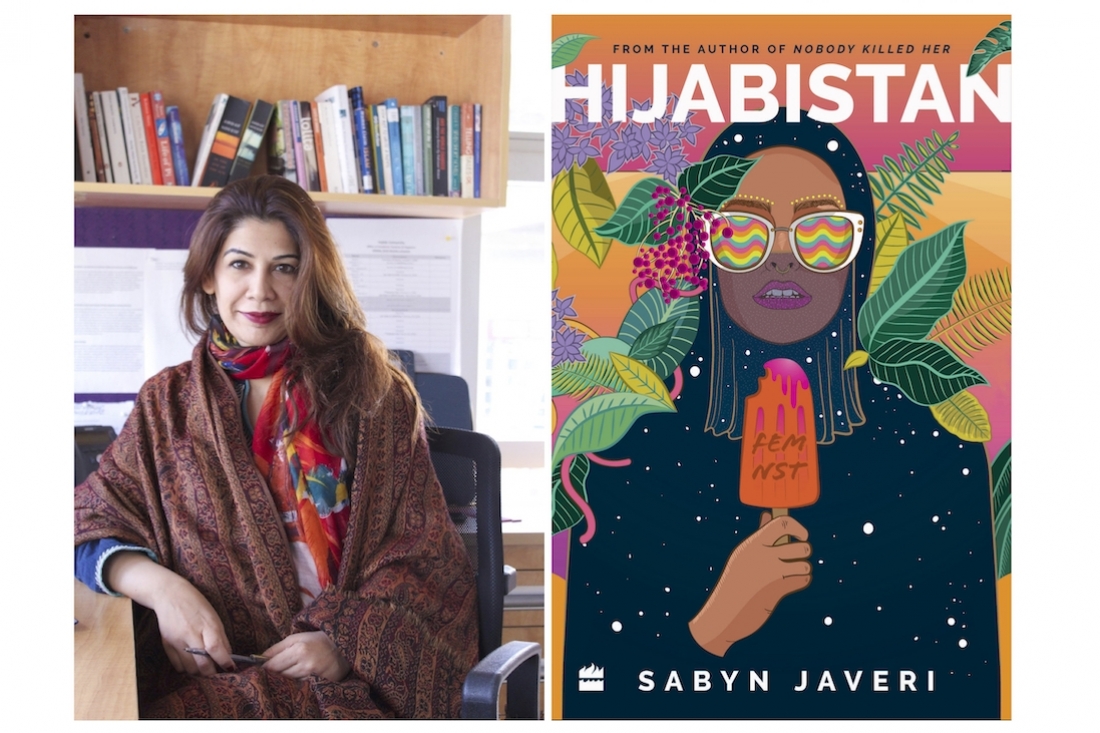

Sabyn Javeri’s writing is unapologetic and important. Using the leitmotif of Hijab in her new anthology of short stories, Hijabistan, Javeri alerts the reader to the different facets that comprise the identity of a Muslim woman. Subversive in its entirety, the books highlights all the stereotypes and biases that are attached with the world's view of the Hijab today. The 16 short stories, each unique and intriguing in its own way, Hijabistan, is also an important work, signifying Pakistani literature. The book's cover art by Samya Arif powerfully illustrates Javeri's work.

We connected with the author to know more about her relationship with literature and her new book.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and why you ventured into the world of writing.

I was sick of reading pretentious dead white male writers and not-so-dead non-white male authors who claimed to be speaking for the whole world with their pen. But they were not telling my story, nor of the woman next to me, or across me. Their fictional worlds were dominated by the male gaze and usually centered around a male character whose point of view dictated the story. Women characters were wholly good or thoroughly evil. They were oversimplified cutouts which lacked complexity. So I decided to tell the stories I wanted to hear. Simple as that.

As for me, I’m a professor of literature and creative writing and a working parent, a rare oddity in the South Asian literary world where writers are mostly privileged enough not to have a day job and can afford to write full time. I wish I could say I am from a literary family but I’m from a family of jewelers and complainers, in that order, and the only odd one out who loved to devour books. I think anyone who grows up in a literary household can pick up a pen but when you grow up in a house with very few books and still manage to write, I think that is quite a challenge. I still remember that when I told my father I wanted to study English in college, he looked amused and said, ‘But you can already speak English, why do you need to study it?’

“I was sick of reading pretentious dead white male writers and not-so-dead non-white male authors who claimed to be speaking for the whole world with their pen. But they were not telling my story, nor of the woman next to me, or across me.”

What are some of the early readings that have influenced your work?

Fairy tales! I still remember feeling outraged and asking my Nani Ami, why does every princess need to be rescued by a prince? Why don’t they just get up and take charge? And most importantly why is the step mother always portrayed as the evil one? The last one upset me the most as my mother was a second wife and a step mother to my elder siblings. I think those fairy tales set the feminist motions rolling in my mind from an early age. And I knew somewhere deep inside that there was another side to these stories. Growing up trying to see things from a different perspective really helped me develop a style for storytelling that was creative and quirky. I like to believe there are three sides to every story and that’s what I try to seek.

What inspired Hijabistan?

I believe we are all made up of stories. The stories we tell others, the stories we tell ourselves and the stories we don’t want anyone to know. Being the sceptic that I am, I suspected there was more to the hijab than meets the eye. Yet I was not interested in stories behind the veil but rather beyond the veil. When I first started writing this book it was going to be stories about brave women who went about their lives wearing the hijab but when I got into it I realised that was the story I was meant to hear. So I decided that was not the story I was going to tell. Instead I became interested in the stories they didn’t want anyone to know. And so Hijabistan became more of a metaphorical interpretation of the veil, of what was hidden and untold.

“I believe we are all made up of stories. The stories we tell others, the stories we tell ourselves and the stories we don’t want anyone to know. Being the sceptic that I am, I suspected there was more to the hijab than meets the eye. Yet I was not interested in stories behind the veil but rather beyond the veil.”

Your work is subversive and unapologetic. Can you take us behind your writing process?

I have come to a point in my life where I think there is nothing to fear but fear itself. And this realisation came when I read Ismat Chugtai’s The Quilt (Lihaaf) and realised it was written almost 80 years ago. I realised I come from a very rich literary tradition of fiery, ballsy women writers in South Asia who unlike their male counterparts have written unapologetically about the personal as well as the political, fusing the two together. So building on this tradition, I thought why can’t I do the same?

As a working parent and an academic it’s hard to find undisturbed headspace for creativity so I let my ideas simmer and stew in my head and then as soon as I get a few uninterrupted snatches of time, I transfer those ideas on to paper. For me it’s not a slow and steady marathon but a sprinting race against time. Once I get it down I forget about it. I come back to it after I’ve had a chance to reflect whether this is the story I really want to tell. Once I’m sure, I take my characters out on dates. I talk to them (in my head of course) and really get to know them. Once I know them inside out I feel that’s when they become really wholesome. Otherwise they remain wooden and one dimensional. So I suppose my creative process is this: write when you can and try to understand the depth of what you are trying to do.

Hijabistan is an important book because it signifies the double displacement of Muslim women, cross linking gender and religion issues. What did you intend the readers to take away from it?

Thank you, that’s a wonderful thing for a writer to hear and I appreciate your words very much. I suppose I wanted to point out the oversimplification of Muslim women as if they can all be judged in to a single category by their appearance. I wanted to complicate the question of a Muslim women’s identity, to separate the purdah from the piety and religion from morality.

“I wanted to point out the oversimplification of Muslim women as if they can all be judged in to a single category by their appearance. I wanted to complicate the question of a Muslim women’s identity, to separate the purdah from the piety and religion from morality.”

You are also academically involved in uplifting Pakistani literature in English. What is the current scenario and where do you think it is headed?

It’s depressing because reading for pleasure has been very much eradicated from our culture. Young people only read for grades. If they have time they would rather watch a web series or go on social media rather than read books. Im trying to change that. Not only am I trying to get them to read just for the sake of reading but also write creatively for their own satisfaction. I recently started editing an annual anthology of student work where the best pieces get published. It was very hard to get the funding and to get the project going but now that it’s in its second year more and more students are getting excited about seeing their name in print and more importantly understanding that their stories matter. It is very empowering to know that you have a voice and through literature and story telling I hope to empower may more young voices.

What are your plans ahead?

My next project is perhaps my most controversial. I want to do a feminist retelling of popular traditions and tell them from a female point of view. Why? Because History is always told from the point of view of the victor but as they say if you really want to hear what happened in the jungle don’t ask the hunter, ask the prey.

Text Nidhi Verma