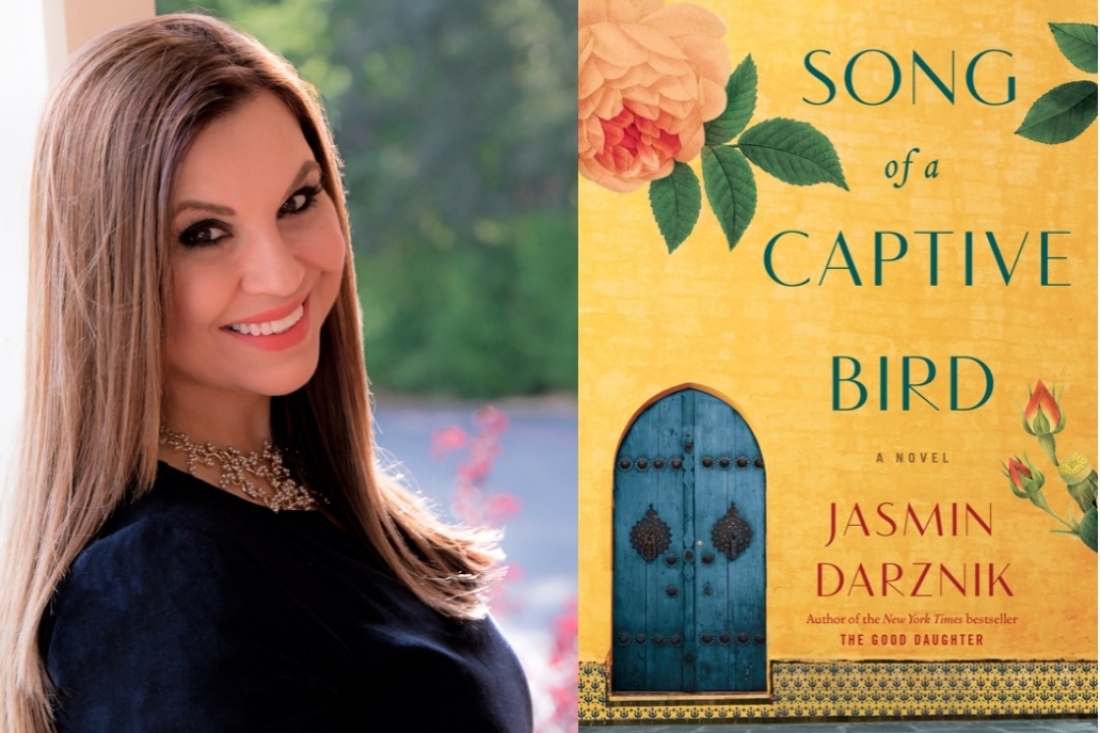

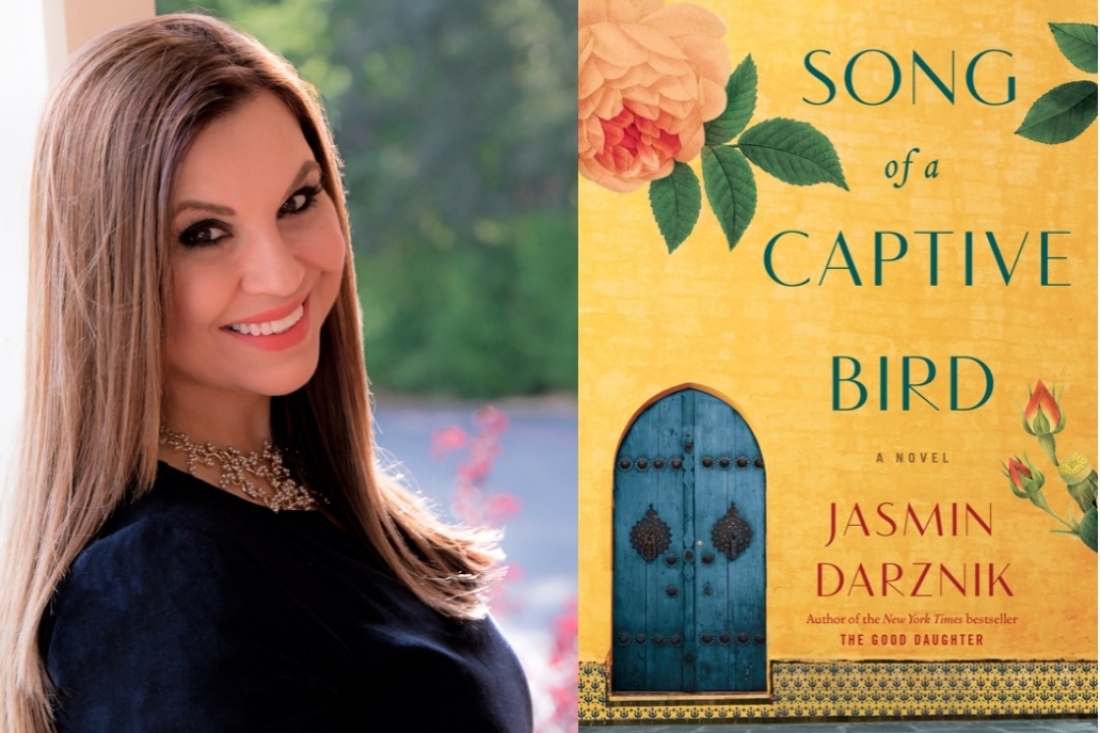

There is poetry in the very name that is Persia, now Iran. Rumi, Hafez, Omar Khayyam are only some of the voices we know today that rose to create refuge amid the atrocities of war. Our debut novelist for this issue, Jasmin Darznik found her hero in Forugh Farrokhzad, whose poetry, honest and piercing, challenged an order set for women through centuries even as she died young, at 32. Jasmin’s book, Song of a Captive Bird [reminiscent in its title of Maya Angelou’s caged bird], is the story of a woman coming into her own power in a culture that seeks to silence and diminish her at every turn. I try to understand what makes Forugh’s story a relevant and important one, and Jasmin’s own journey in finding and recreating her.

Tell me a little about yourself and how you began your journey in writing.

I wasn’t supposed to be a writer. Nothing in my immigrant background supported it, and a great deal impeded it. Still, I was a reader. As a child I left my small town library with novels stacked up to my chest and under my chin. I’d go home and luxuriate in the possibility of disappearing into different worlds. Beyond that was the twenty-room motel my parents bought when we immigrated to America, a place rife with the grim certainties of life on the margins. Books were my way out. Specifically, fiction was my way out.

But writing? Even as I hacked away at the prohibitions set down by my family, it still seemed impossible. I only discovered memoirs when I was in my 20s and working toward a PhD in American literature. As I read Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on the Road, I found myself profoundly moved by the feeling that these writers weren’t just telling me a story—they were telling me who they were. Having grown up in a family where telling people who you were could be, and often was, regarded as a betrayal, these works were both a revelation and a provocation. I became a compulsive reader of memoirs. And then I wrote my own.

What inspired Song of a Captive Bird?

The novel started with an obsession—an obsession with Iran and one of its most legendary women. For many them many years I’d read all I could about Forugh, not knowing it would lead me to write a novel. Then at one point I discovered she’d assisted some student activists during the turmoil that roiled through Iran in the early sixties. I set about learning all I could. I returned to her poems, then to scholarly sources. Discovery piled onto discovery. The least welcome, but perhaps most energizing, was her total invisibility outside Iran. Eventually, I thought, I have to tell this woman’s story.

“Forugh’s life was shot through with drama, and I actually had to make up very little in terms of the plot. The novel’s strongest fictional intervention was to render her interior life, to give a reader a sense of what it felt like for her to live the life she did.”

Can you draw a picture of Forugh Farrokhzad as you see her? What about her poetry drew you in?

I see Forugh as both tremendously powerful and hauntingly vulnerable. She was not afraid to show who she was, and given her time and her culture, this was a huge risk—and one that cost her again and again. What strikes me most of all about her poetry is its honesty. Her poems are often quite beautiful, but that beauty is always in service to telling some essential truth about herself or the world.

It is not easy to base a novel on a true subject...

Forugh’s life was shot through with drama, and I actually had to make up very little in terms of the plot. The novel’s strongest fictional intervention was to render her interior life, to give a reader a sense of what it felt like for her to live the life she did. My rules were, firstly, that my inventions and imaginings couldn’t contradict any known facts and, secondly, they had to feel consonant with what I knew to be true. Fortunately there was still space for surprise and discovery.

What is the relationship that you share with poetry? What does it mean to you?

You’d be hard pressed to find an Iranian who doesn’t adore poetry, even if it’s just one poet or one poem they read or recite again and again. With such a turbulent history, poetry has been a refuge for Iranians. A place where they find wisdom and beauty. A vessel for their pain and longing. I grew up with a sense of the grandeur of Iranian poetry, but Forugh’s was the first voice that truly moved me. Nowadays I read very little poetry, but I do retain that very Iranian reverence for language and story-telling.

“I move from obsession to obsession. I read absolutely everything I can about a subject, working myself into a trancelike state.”

How have your roots and your personal history impacted this work?

I left Iran when I was so young, but Iran has never left me. Iran is my mother’s life, and my grandmother’s; through them I feel bound to the culture, and endlessly nourished by it. I think I have always been searching for them through my writing. It’s a homecoming to a country I may never return to again.

What was the toughest part of making this debut? How long was it in the works?

I worked on the book for about four years. There were many junctures when the project felt impossible, not least because I’d been made to feel Americans didn’t care to read about Iran. Maybe as a news story, but not in a novel. So I’d say the toughest part was shutting off those voices that told me what I was doing didn’t matter. I think half the work of writing—more maybe!—is cultivating a sort of crazed belief in yourself and your work.

Can you take me behind your creative process?

I move from obsession to obsession. I read absolutely everything I can about a subject, working myself into a trancelike state. Often it’s a small detail, some footnote, that leads me into a story and sets me on my way. Another way I think of it is that I’m designing and solving a puzzle at the same time. Which is more than a bit insane, but there you go.

Who are the authors that inspire you?

My favourite authors, the ones I return to again and again, are Isabel Allende, Sarah Waters, and T.C. Boyle. I recently discovered Pat Barker, and I am in awe of her ability to bring the past to life, and in such gorgeous prose.

What is next from here?

I’m working on a novel set in San Francisco during the 1920s. In some ways it’s quite like my two previous books in that it’s about feisty women cast into impossible situations. It’s wonderful, though, being able to visit the places I’m writing about this time around. That San Francisco no longer exists, but its ruins and its ghosts do, and I’m making my home among them, word by word.

TEXT Soumya Mukerji