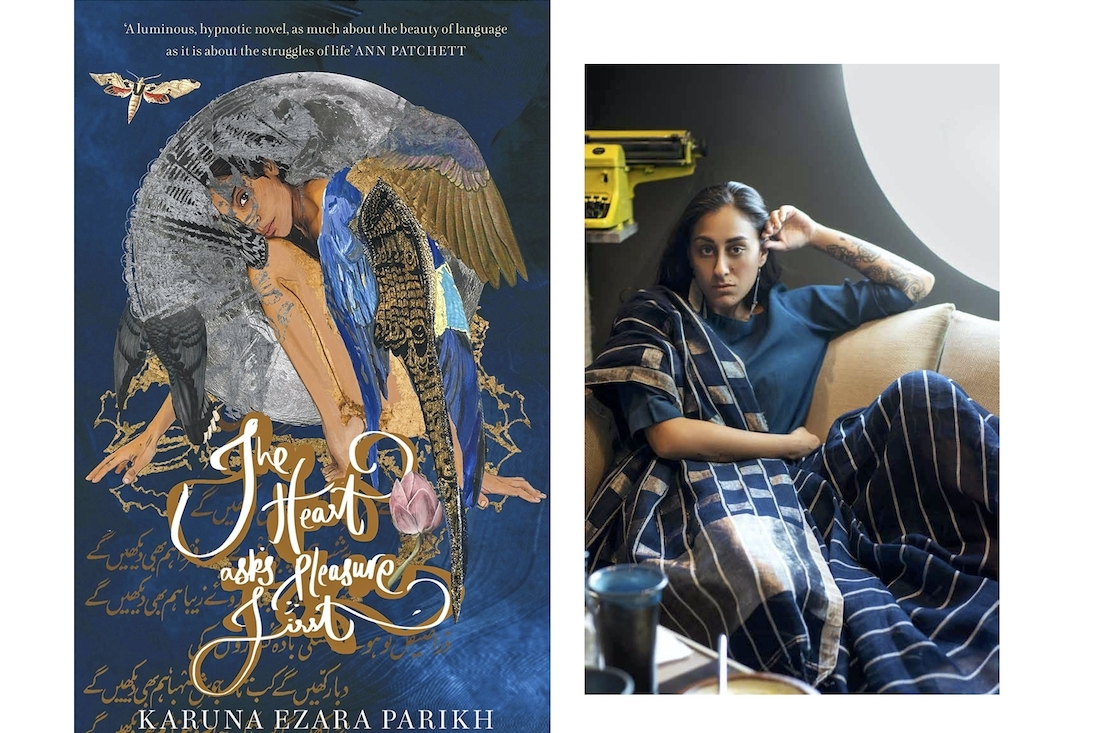

Photography: Nayana/ Team PixelAmalgam

Photography: Nayana/ Team PixelAmalgam

Karuna Ezara Parikh is many things. A spoken word poet, a screenwriter who has worked on films as Kaash with Ishaan Nair, part of the showrunning team at The Burlap People, TV journalist – and now, an author. What does it take for one of the most diverse talents in the country to pen her debut – to funnel her being in neatly folded words?

An exploration.

Tell me a little about your first memory of the written word, and how you began your journey in writing.

Ah, I’m not sure. I cannot remember ever not writing. I remember reading Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address and realising that everything I had read until that moment was child’s play. I must have been 12, and I was reading all the young adult stuff one is meant to and then I read this, and I knew immediately that it was different. It’s only later, more recently, that I sort of stopped and said to myself, ohhhh that was the shift to literature! At first I wrote poems - note- books and notebooks full of them. But I didn’t know you could “be a poet”. I didn’t understand how one could. I would send poems to the newspaper. No one ever wrote back of course. I think it’s why I studied Journalism eventually. It was the only way I thought I could, maybe, make any money writing.

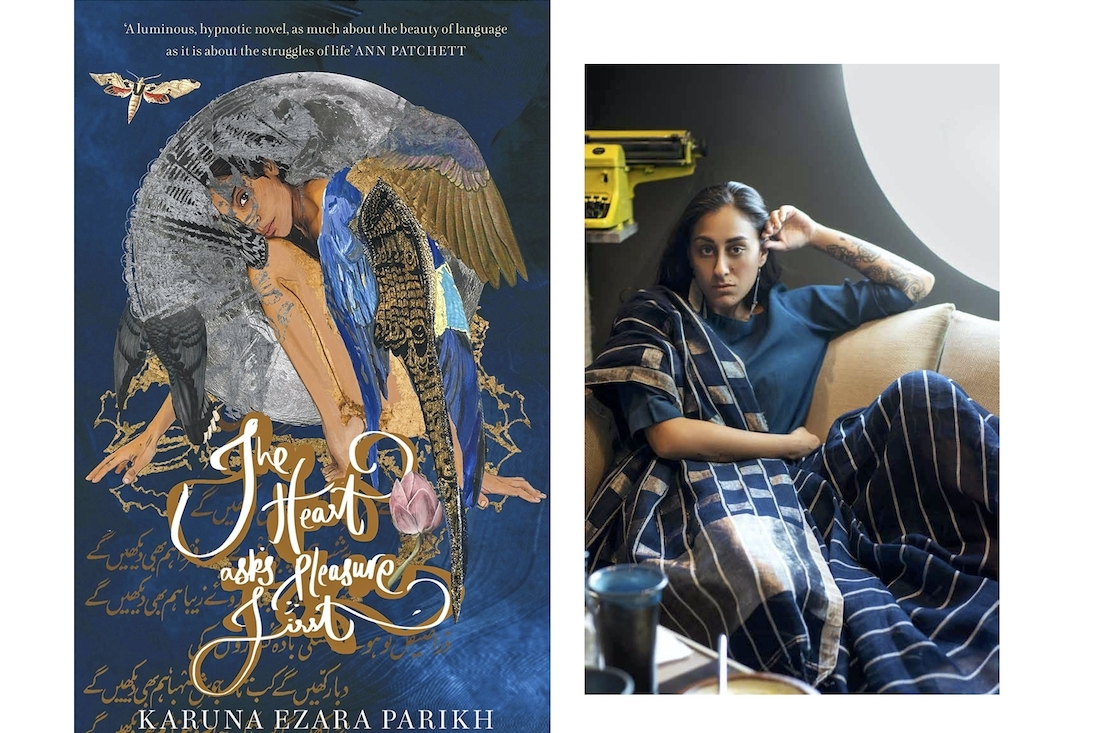

What inspired The Heart Asks Pleasure First?

In 2003 I met a group of Pakistani boys and became very embedded in friendships that felt very much like home and family. Our conversations and connections over the years became the lens through which I viewed Indo-Pak relations in some sense - devoid of politics, steeped in similarities. The story began to brew at the time and I knew I always wanted to write something that dealt with the complexity of those friendships but which was rooted very much in today and not at the time of partition. Yes, it’s impossible to write about India and Pakistan together without referencing 1947, but there are new stories to tell as well.

Over the last two decades the way we view Islam has also changed, globally, and the urgency to tell my story grew. It finally fell into place when I met a man who made me question everything I knew about love. I’ve been told I “only write love stories” and perhaps that’s true, but aren’t all stories love stories? When I combined my humongous learning of love with the anger and frustration I had felt politically for so long, a story became ready to be written.

Can you give me a blurb on the book in your own words?

Oh I’m terrible at this. I’ll try—The Heart Asks Pleasure First maps the relationship of Daya, an Indian Hindu student of dance in Wales, and Aaftab, a young Muslim lawyer from Pakistan. Away from home, the two collide and begin to create a world of their own. Set in the early aughts, the story attempts to view the difficulties of their love through the changing international ideas of Islam at the time. The other important characters in the book are Daya’s parents—Gyan and Asha. But I won’t say more now.

You’ve been a writer of many things – film, script, poetry et al. What are your views on form and fluidity?

I meet a lot of writers of brilliant, brilliant books who say—Oh I could never write poems! And I think, oh but you could. Maybe that’s coming from a place of per- sonal comfort, because I switch between forms of writing, and it’s true that maybe some people cannot. I’m not sure why that is, but yes, I’ve ended up in some sense being the opposite—a jack-of-all-trades. As a young journalist I often wrote pieces on demand, and the tone had to be different for each one. Did that give me practice in this switching about act?

One of the reasons I continue to use all forms is that they each satisfy a different aspect of me. Writing prose satisfies my biggest dreams, my heart and in some sense my ego. Writing poetry is more communicative, it’s important, it’s urgent and it’s soul work. Writing scripts is monetary but is also the least lonely way to write. Writing articles is a combination in some way of the last two. If I had to choose a single one, I want to say I would choose prose. I would write books and nothing else. But I’m not sure I can choose. Would giving up one be giving up an aspect of myself?

What is more challenging—the spoken word or the written word?

For me, definitely the spoken. I’ve suffered from terrible stage fright for a lot of my life so it was active work to become comfortable speaking on a stage, doing poetry readings etc. It’s one of my life’s profound personal achievements that I can do so now with joy.

What was the toughest part of making this debut?

My agent Shruti Debi is brilliant, but she is so brilliant because she is patient and pauses for everything. She thinks things over and always comes back with insight I could never have predicted. This takes time, and hard work on both our parts. Rewriting takes time, culling takes courage, and waiting takes every single thing out of you. Once the book is sent to publishers, sitting and wondering if your years of work will be validated with an offer... that’s hard. If I’m to be honest, the hardest part is actually writing it. Now that I’m done it’s easy to forget, but it took 10 years of writing and rewriting. The final version has less than two pages of the first version I ever wrote.

Can you take me behind your creative process?

I write longhand to begin with. I really believe in pen to paper. I try and tell a story only once I know where it is going. I live with my characters. It’s madness, but coming out of that madness is only possible by immersing yourself and swimming through it. So for example I’d be cooking dinner and asking myself—would Wasim [a character in the book] cook this? Would he like it spicy? I’m a bad researcher. I go down rabbit holes. I might for example read for three hours about the Suez Crisis for a single line in the book. It’s terrible. It stems from insecurity—do I know enough?

When I’m writing, I am always writing. I wake up in the middle of the night with lines in my head and I have to make notes on my phone immediately. I’m a day writer though. That’s how I wrote this book—morning to night. And every evening when my husband would come home from work, I would read all the new bits to him and ask him “Is it good?” a thousand times. He’s my first reader. Then Shruti. They’re sharp critics, which is important.

Who are your favourite authors, both old and young?

Tom Robbins, Tom Wolfe, Nadeem Aslam, Sara Suleri Goodyear, Barbara Kingsolver, Svetlana Alexievich, Joan Didion, Zia Haidar Rahman, Richard Powers, Galeano,Ondaatje... The list is quite endless. Does it have too many men and white folk on it? Probably. Am I trying to change that actively? Definitely. With choosing favourites I often wonder if I’m meant to choose only the authors whose entire published lists I’ve read, or if you can choose someone for a single, remarkable work.

What is next?

I’m not sure. The book releases in the Spring after which I have a book of poems coming out with HarperCollins India. I think that’s quite a lot for the coming year. I’ve thought about if I’m meant to be actively planning a second novel, but that seems forced. Seeing as this one took 10 years to make, I’m not sure I could force a next! I think the right subject matter will come to me with urgency when it has to. When something feels urgent enough, I will leap into it. And for now, lots of tea and sitting back with amazement at having made it this far in more or less one piece.

This conversation was initially published in our October 2019 Bookazine. The book is now available for purchase on all platforms.

Text Soumya Mukerji