Author portrait by Sharad Shrivastav

Author portrait by Sharad Shrivastav

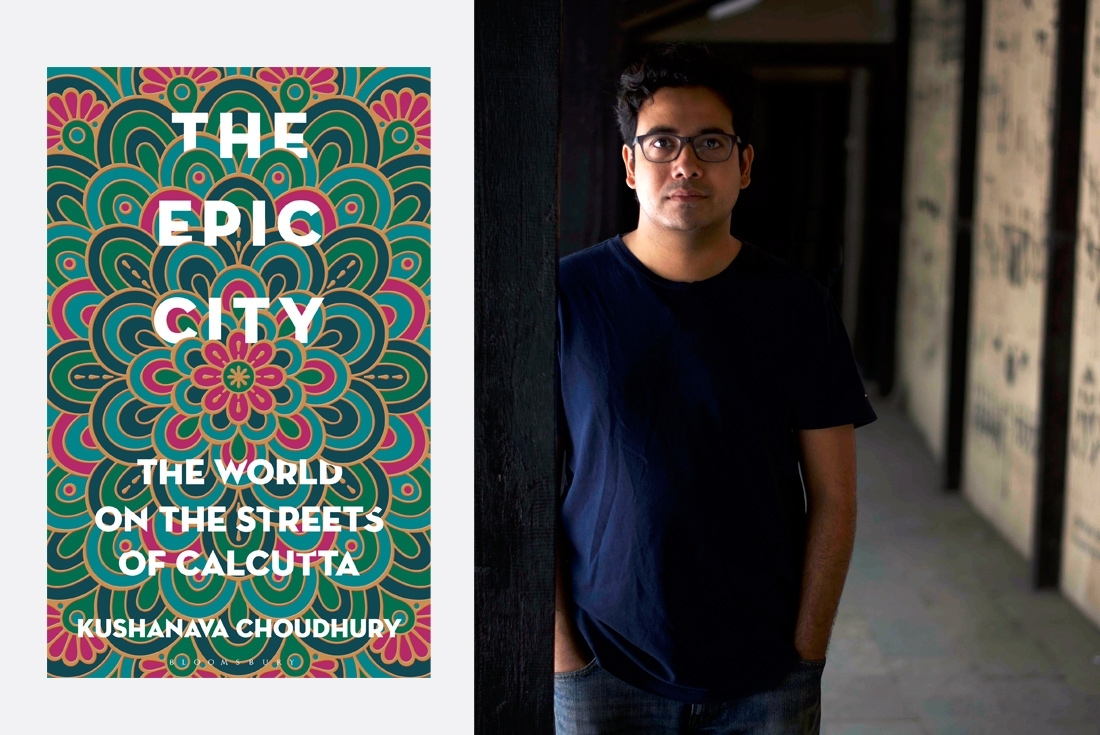

Each one of us has an epic city. Someone’s soul is all Bombay, for me it has to be Delhi and others’ hearts reside more in New York than they do themselves. What then, makes an epic of a city to someone? A collective and personal history, a present and future continuum woven deeply into our lives, or the city as a creature that stands unto itself, just a witness and a fine trickster that like a top makes us spin? Debut author Kushanava Choudhury’s telling of Calcutta answers better. He shares how Calcutta happened to him before he happened to Calcutta.

THE JOURNEY

I grew up in Calcutta and then moved with my parents to the US when I was 12. After college, I moved back to the city to work as a newspaper reporter at the Statesman. I walked through the revolving doors of the Statesman to enter countless portals of the city, following streets upon streets, pavements upon pavements, to another life.

I worked there for about two years and went on to graduate school, at Yale University, in the US. But after leaving Calcutta, no matter where I went or what I did, I kept coming back to the city, drawn back by forces that I didn't fully understand or control. My friends used to think I had a secret lover in the city. But it was much stranger than that. I used to stay in Calcutta for months at a time, visiting old haunts, hanging out on street corners, wandering the lanes like a vagabond. The city exercised such a magnetic pull over me that no matter where I went, to New Orleans or Lisbon, Grenada or Barcelona, I was always in search of other Calcuttas. That's why I finally wrote the book, to make sense of the city and my relationship to it.

THE DEBUT

This is the story of Calcutta in the 20th century, and of my fraught attachment to the city. There’s an epic scale to Calcutta, which envelopes you and does not let you go. This book seeks to capture the totality of the overwhelming experience of Calcutta, where every detail—from the conversations at the local tea shop, to the rallies of the then—ruling Communists, to the events that produced the Partition of the subcontinent, are part of one narrative of the city, an all-encompassing narrative of epic scope. All the characters are real. I met them.

THE PROCESS

First, I follow my intuitions and hang around in places that interest me. I talk to people and listen to their stories about how they see the world in which they find themselves. I listen to myself too, because most of the time I'm not aware of myself, of why my subconscious is taking me down a lane that looks like a dead-end. I take notes in a notebook that I always keep in my back pocket and then go home at night and write down everything I can remember or that comes into my head. I do this for many months until the money runs out or some other external force makes me stop. Otherwise I could do it forever because I enjoy this part of the work. It's when I'm learning the most because I'm meeting new people and seeing new places, and I find that endlessly interesting. It's like being a wanderer for a living.

Seamus Heaney said that poets are like amphibians. First they have to go into the welter of experience and pull out rough treasures. Then they have to burnish those artefacts on the shore. That's a pretty good description of what I do also. After the collecting phase, I have to sit in a room with all that stuff laid out on the floor trying to figure out what I've gathered, writing on the wall everywhere like the writer Shibram Chakraborty whole roomed his whole life in a boarding house near College Street. Then I write out a first draft that gathers all that stuff into one text, which takes six months to a year.

After that, it took me years of sitting in a room alone to revise that unreadable text into something resembling a book. The revision process was my apprenticeship, my real graduate school. Most of what I wrote in those years, which came to several hundred pages, got left on the cutting room floor. By doing, I learned how to write something that looks like a book.

THE PROFESSION

I have worked as a reporter, a teacher, an academic and as a writer. But I don't have a career or a profession. The reporting, the teaching, the research and the writing are all part of who I am and how I see the world. I basically know how to do three things: read, write and talk to people. That's how I live and that how I write. There's no difference between the two.

THE CHALLENGE

It takes a long time to write a book, especially when you don't know what you're doing. Writing a book is like swimming. You can only learn how to do it by doing it, by flailing, getting water up your nose, almost drowning, before you finally, awkwardly learn to float for a little while. Maybe someday, when I'm middle aged, I'll learn how to do the backstroke and the butterfly.

THE FAVOURITES

Syed Mujtaba Ali, Bohumil Hrabal, Phillip Roth, Junot Diaz, Roberto Arlt. Roth and Diaz because they are the gurus of the New Jersey gharana of American literature, to which I also belong. Syed Mujtaba Ali, because he was the master of the adda mode of writing, a polyglot and pandit whose greatest vice was that he was not boring enough to be respected as a difficult writer. Bohumil Hrabal because he was wrote the history of the 20th century in picaresque form. He is such a seductively entertaining writer, like Mark Twain, that you almost never realise that his version of our times is more true than that of a hundred apparatchik historians. Roberto Arlt, because nobody knew how to bring the world of the street into literature [or journalism] like him, except maybe Truffaut in 400 Blows, if we're counting films.

I will never be as good as any of them even if I write for another 50 years, but these are a few who I learned a lot from while writing this book.

If we are counting movies, then Ritwik Ghatak's films had an enormous influence on me, because they tell the true story of Bengal in the 20th century. Only Ritwik seemed to understand the centrality of Partition at an existential level for Bengal. Everyone else seemed to treat it like an event, a calamity that happened at one point, like an earthquake or a flood, and then stopped, and from which we recovered, as people recover after a flood or an earthquake. Ritwik understood Partition in terms of the breakdown of the self. His films are about the collective unconscious of Bengal. He was very intentional about this in his films, as he writes in his essays on filmmaking. If we don't fully understand his films, then it’s because we don't yet understand anything about what Partition wrought, what it continues to wreak upon us. Because Partition never ended. It's still going on. Maybe in another hundred years we'll understand it; then Ritwik's films will be invaluable.

THE FUTURE

I’m writing a novel about murderers and shamans in Connecticut. It’s about race cleansing, American amnesia and ghosts of the past.

Text Soumya Mukerji