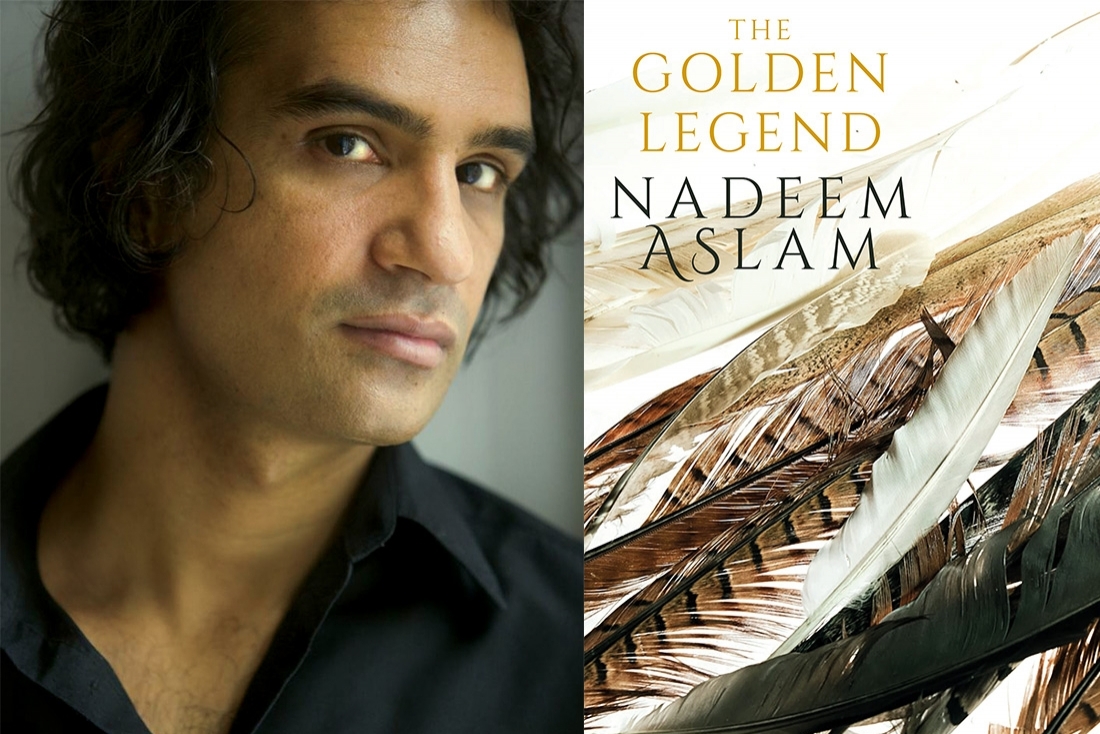

Photo © Marco Varrone

Photo © Marco Varrone

It’s been a long journey for Nadeem Aslam, and the British-Pakistani author is happy straddling the two worlds that inspire his art. The award-winning writer informs that his new work of fiction, The Golden Legend, was inspired by all fact—‘I do not have the imagination to compete with reality’. In the course of a beautiful, detailed recounting of all that created the Legend, he builds an interesting analogy around Trump’s new code of dishonour and the role of artists in the new world order:

‘Everywhere is part of everywhere now. That interconnectivity was one of the things I was trying to explore and convey in The Golden Legend. The world seems obsessed with divisions at this historical moment. Donald Trump wishing to build a wall reminds me of a beautiful painting Frida Kahlo made in the 1930s, standing in a pink dress on the border between Mexico and the USA. I look at that painting, and think: If they wish to build a wall we can’t stop them; but we’ll be the Frida Kahlo standing on that wall, defiant, in the most beautiful clothes we can find. Their summer lasts a solid year, Emily Dickinson said of poets. That’s what art is, that’s what I want my novels to be.’ Amen.

What is your first memory of writing?

I don’t have a first memory of that. I have always written, even as a child. I have dedicated my life to my writing and I don’t mind challenges and struggles as long as they have a meaning. I am not one of those writers who hate writing: I suffer with pleasure the difficulties writing poses me.

When I come to a problem during the writing of a book, I am frequently in the same position as my characters. If I don’t know how to get a character out of a locked room, the character too doesn’t. So I have to patiently think about what is available to the character and to me—what are the options. So with Nargis’s secret, I had to go through her life, year by year, and think about how she would manage to keep her secret in this or that situation. I had to live her life with her—and then see what kind of a person she would be by the time we meet in her fifties at the beginning of The Golden Legend.

People always ask: How much of your own experiences do you use in the novel? I sometimes feel that I don’t have any imagination. Everything I write about is taken from real life. One day at school my six-year old nephew had looked up and said, ‘My uncle Nadeem is here!’ The teacher told him that that was not the case, but he kept insisting—‘My uncle is here.’ He remained a little agitated, and at the end of the day when his mother went to collect him and was told of this, she questioned him: It turned out that because I write by hand, with a fountain pen, in my nephew’s mind the smell of ink is associated primarily with me. And someone had broken a bottle of ink in the office next to his classroom—he was smelling it all day and thinking I was nearby. Now, my nephew obviously hadn’t read Proust; it was Proust who had observed and studied the workings of the human mind and put it into his great novel, a novel that is a comprehensive study of how the various remembrances and sensations and tastes and sights are associated with each other within our consciousness. So it is that life precedes art.

In Pakistan, some years ago, I met a young Kashmiri man who said that the Indian soldiers had beaten his pregnant sister so savagely that the arm of the foetus was broken. That happened in The Golden Legend now. How could I have made that up?

Without revealing too much about the plot, what Bishop Solomon does in the second half of The Golden Legend, as a protest against the persecution of Christians in Pakistan, is similar to what was done by Bishop John Joseph in real life in Pakistan, in May 1998. I say this to emphasise again that I do not have the imagination to compete with reality.

What was the event that inspired this novel?

In January 2011, when I was working on my previous novel, The Blind Man’s Garden, the governor of the Punjab province in Pakistan, Salmaan Taseer, was murdered by his bodyguard. The governor had objected to Pakistan’s blasphemy law, a law that is being misused. You can go to a police station and say I heard my neighbour say something rude about God or Muhammad, and the police arrest the neighbour and you can move into his house. Innocent people are dead or in jail because of that law.

Entire Christian neighbourhoods have been reduced to ashes by mobs accusing Christians of blasphemy. Just last year a Christian couple was thrown into the furnace of a brick kiln by a mob, for blasphemy. People think they have the support of the state; they feel emboldened. The governor was killed on 4 January 2011, and that very afternoon I decided that as soon as I finish writing The Blind Man’s Garden I would write a novel about Pakistan’s blasphemy law. I began to make notes about The Golden Legend that very day.

I started writing the novel the day after I finished The Blind Man’s Garden.

Can you give me a blurb on the book?

The answer to the previous question is only partly what this book is about. Did the book change when I began to write it fulltime? Yes. The initial impulse of 4 January 2011 deepened. From the treatment of the Christian minority in Pakistan, it became a novel about the relationship between power and powerlessness. What does it mean if you are powerless? The sentence in the novel is: Even a deformed rose had perfume. Who is powerful and who is powerless in relationships between men and women, between East and West, between adults and children, between a state and its citizens, between the majority population of a country and the minorities.

How do you observe the South-Central Asian landscape—mostly a constant in your writings—changing through the decades as you create narratives around them?

I am a political writer. Literature means no one is forgotten. President Obama authorised thousands of drone strikes during his presidency. The reader doesn’t have to take my word about the possibilities of sheer horror within that statement. I would like my readers to Google the term ‘fun-sized terrorists’ and the report would come up. An American former-drone operator telling us that when he and his fellow operators saw children on the screens of their control rooms, they referred to them as ‘fun-sized terrorists.’

One of the things I was attempting to do with The Golden Legend was to examine how the politics of a place filters down to ordinary human beings. Let’s look at the headlines from around the world. The Sultan of Brunei has banned Christmas celebrations, with a possible 5 year prison sentence for those who break this law; Malaysia has banned Shia Islam; Saudi Arabia has declared that the ‘incitement’ to atheism is ‘a terrorist act’; a few days before the 2017 New Year massacre in Istanbul, a youth group in the city had carried out a mock execution of Father Christmas; in 2016 the Muslim call to prayer was made for the first time since 1931 in Hagia Sophia; and in an increasingly Hindu fundamentalist India, a Hindu woman was murdered by her uncle in India in 2016, a few days before she was to convert to Christianity. And in England we have Brexit; and a man feels completely at ease walking around in a T-shirt that reads WELCOME TO ENGLAND, NOW FIT IN OR F*** OFF.

I remember a time in my twenties and early thirties when, while reading a newspaper, I would get anxious the closer I got to the innermost pages. That was where most of the ‘international’ news was, the news from the non-Western world. The massacres and the unrest and injustices of the developing world—a part of the world I felt connected to deeply. But increasingly as the years have gone by I am anxious on the very first page of the newspaper.

The book introduces an alternative perspective to life in the country amid communal violence, as you introduce some unusual protagonists who defy the Pakistani stereotype—Helen and Imran, for instance. What made you pick them?

I was in the earlier stages of the novel when I came across The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine—a 13th Century collection of the lives of the saints. It was one of the first books printed by William Caxton in English. The novel is set in a fictional city called Zamana—which in Persian and Urdu means ‘the world and all it contains’; or ‘the age’; the zeitgeist.

The Golden Legend is the story of our times, of the encounter between worlds and cultures. I wanted to look for the moral centre of today’s world, and wanted the characters to be like a series of icons [not unlike the saints], representing grace, love, honesty, endurance, sacrifice etc. That is where Imran—a boy from Kashmir —and a Helen—a Christian girl—came from.

The book took four years to write and very early on I felt that a central icon was missing from the story. I also felt that it had to be a woman. [A character in the novel thinks: She had never realised how alone women were in the world.] It had to be a Madonna and child. There are any number of beautiful images of Mary and the Christ child—Botticelli’s Madonna of the Pomegranate; there is Madonna of the Pinks; Madonna of the Goldfinch; Madonna of the Rocks. And I thought I should update them and have a 21st century Madonna. A Madonna of the Drones. That was when the characters named Aysha and her little son Billu entered the novel—a young boy whose legs had to be amputated after a missile fired by an American drone fell onto their; it killed his militant father but maimed him.

I paint and draw, and while writing The Golden Legend I made several sketches of this Madonna and Child and pinned them to the wall next to me. So it did become an icon—the little son has no legs and is held on the mother’s lap, and both have haloes of missiles and drones.

I love reading as much as I love writing; so there was another text with the name The Golden Legend. An 1851 poem by Longfellow. It begins with the extraordinary image of the Strasbourg Cathedral in a great storm. It was the tallest building on the planet for most of Longfellow’s life, and in the opening verses of his poem Lucifer and his spirits are trying to wrench the cross from its spire, the winds howling around them. And they flee when the bells ring. I would like to think that that spire and the minarets in my novel—the minarets that broadcast people’s secrets at night—are somehow linked; as is the idea of two lovers who embark upon a dangerous journey in both Longfellow’s poem and my novel.

What is your definition of an ‘outsider’ and that of ‘belonging’, two important words evoked during the reading of your book?

My memories and my ability to read Urdu are my two most treasured possessions. Language on the whole is one of my great loves, but I am aware of the fact that I do not use the English language in the same way that someone born in the Britain would. The language I use has the 26 letters of the English alphabet, but they seem aware of the presence of the 38 letters of the Urdu’s alphabet too.

And as with language, so with place: I belong to both England and Pakistan. I always say that I could live anywhere if I loved someone. So I would be happy to belong to a third country too.

One of the most shocking things I have heard in my entire life is Theresa May saying, ‘If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.’ Antarctica is mentioned in the second sentence of The Golden Legend because I wished to invoke a continent that is still largely undivided and unclaimed. Tolstoy said that patriotism is slavery; and at the deepest level of self, I am unable to accept the demarcations between countries. It’s your country, but it’s my planet. The line that is drawn is yours, but the paper on which it is drawn belongs to me and to people like me. My loyalty is to humans and the planet, and in that sense I feel able to question the conduct of the powerful anywhere in the world.

American drones are sending down missiles into Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere—but I also know that in 2008, according to Bob Woodward’s book Obama Wars, the then-President of Pakistan Asif Zardari had told the CIA’s director general: ‘Collateral damage bothers you Americans, it doesn’t bother me.’ This is a president talking about the possible deaths of his own citizens.

The past and the present meet like both friends and foes throughout the story. How do you think a country can make peace between both?

The question of our age might be: What means are justified in putting an end to moral crimes. Our principles are being put to the test by various conflicts.

And in many ways, none of this new—neither the strategies for survival of the powerless, nor the shamelessness of those who wield power. That is where hope is – the knowledge that it has happened before, that it is happening in other places right now, not just yours. It calls for solidarity. Through solidarity and love people managed to undermine unjust systems. In December 1974, my beloved master Gabriel Garcia Marquez had met the CIA whistleblower Philip Agee in London [Garcia Marquez was forbidden entry into the USA at the time.] They two men talked, and Garcia Marquez later wrote that during their intense conversation they reached a point where they were ready to absolve the CIA of all blame. He wrote: ‘In fact, with all its money and power, the CIA could not have accomplished a thing without the connivance of the governing classes of Latin America, without the venality of our civil servants, and without the almost limitless possibilities for corruption that are open to our politicians.’ In Pakistan’s case I would add the corrupt military men and the dishonest mullahs. Sometimes I feel that at the most profound level, all my novels—The Golden Legend, included—come out of that one sentence of Garcia Marquez.

So: love and solidarity, always.

My work has both beauty and the terror of existence—my aim is to show the ugliness without destroying the reader’s capacity for love and happiness. I wish to celebrate the fact of being alive on this planet. Living inside this body with its five senses. And, once again, it all comes from real life.

In The Golden Legend there are two large architect’s models—one of the Hagia Sophia and the other of the great mosque in Cordoba. They are in a large library and are used for working in during the months of winter cold. It’s based on an image I saw in a television program about an English lord who had fallen on hard times: his once-magnificent manor house was now mildewed and falling apart, and he lived in a garden shed placed inside the massive banquet hall. The cold hall was lined with suits of armour; there were large paintings and a dinner table meant for dozens of guests, and there was the warm wooden shed in which the gentleman lived.

My sense of the ordinary and the extraordinary frequently seems blurred. It’s the viewpoint of a convalescent, of someone encountering life after a period of illness, even receiving the world for the first time. I live in Yorkshire and there are farmlands and orchards nearby where I take regular walks. During one walk recently I was making a drawing of a fungus growing on a fallen log, when an orange-bodied sawfly cam and landed on the very tip of my pencil, a few millimetres above the surface of the paper. I flicked my wrist to make it fly off, but it wouldn’t. I clung on as I continued with my drawing—I must have made about two dozens marks and lines before it decided to fly away. As I was walking away I asked myself whether what had happened was ‘ordinary’ or ‘extraordinary’. I still am not sure. At one level that is where I wish to be when I am writing—to be in an indistinct place. I love London and miss it when I am not there but I am on constant guard against complacency when in large and important places, always remembering Jonathan Swift who said that it is the folly of too many to ‘mistake the echo of a London coffeehouse for the voice of a kingdom’. I feel most at home on the margins.

What was the biggest challenge thrown in your face?

The challenge is always the same. To write honestly. With all my intelligence. To honour the things and people I love. To understand what I don’t understand. Islam and Marxism are the two strands of my DNA, my double helix; Islam, which I received from my mother and her family, and Marxism, which came to me from my father and his brothers. Two buckets are easier carried than one / I grew up in between, wrote Seamus Heaney. I am however an atheist, and am delighted that over the past decade the term ‘cultural Muslim’ has been given a Wikipedia page.

I am not Eve’s son. I am Lucy’s son, Lucy being the name given to the collection of bones that come from one of our 3 million year old ancestor. I have never felt wonder ant anything in my adult life. ‘Wonder’ is a religious word, in many ways. Religion says, ‘You are not allowed to think about or question anything beyond certain limits; beyond that lies wonder.’

I however like the idea of questioning and exploring. I trained as a scientist, and take great delight in the fact that when the space probe Juno entered the planet Jupiter’s orbit in July 2016, after travelling a distance of 3 billion kilometres, its arrival fell short by just one second of what the scientists had calculated it to be. I believe that no occurrence in my life has had anything to do with God. But my mother is a practising Muslim and she believes that nothing in my life has occurred without God’s will. Me failing my Maths O level, my brother scoring a century in a cricket match, me falling down and acquiring a scar under my chin as a child, me writing this sentence now—all of it is so because Allah has willed it to be, according to my mother. The Garden of Eden existed, it’s not a metaphor, just as Jonah being inside the whale is not a metaphor for her. The reader could say that this is an irrational mindset, but I must also state that my ideas of decency, love, kindness, compassion were given to me first by my mother—this ‘irrational’ person was the ones who laid down the first few layers in my consciousness of what it means to be a good person. That aspect of religion is something I am deeply interested in exploring in my novels.

Taken purely on a textual level, if I write about the inner life of a person like my mother and her brothers—people who believe in angels, djinns, Satan, Judgement Day—am I writing realism or am I writing magical realism? There are billions of people like my mother in this world—who believe that there is a supernatural explanation for the universe – but what does it mean if a writer chooses not to write honestly and comprehensively about their mental life because, well, magical realism as a genre is too hackneyed now? I feel it would be arrogant to dismiss the concerns of so large a section of the world’s population.

And this is one of the ways in which politics enters the life of a writer, one of the ways he reveals his politics—by what or who he chooses not to see. It all makes me think of Boris Pasternak: Man in other people is man’s soul.

Can you take me behind your creative process as it occurs? Do you still write by hand?

I still write by hand, certainly the first draft of a novel. I draw and paint scenes from my novels to be able to think of them differently. I sleep during the day and get up at 11pm. I am at my desk at midnight and write till 6 in the morning. Then I relax, read, watch a DVD, go for a walk or a swim, read the newspapers. At 10 am I return to my desk and write till 3 am. I drift to sleep around 4pm. The entire process can be repeated for—sometimes—an entire month; I don’t like seeing anyone when I am deep in my writing.

Who are the new writers that you see as promising?

I think Bilal Tanweer from Pakistan will produce beautiful books over the next two decades. From India: I print out with great delight the blog entries of a young writer named Saudamini Deo. I love her sensibility—both in photographs and in text. What I like in writing is what I like in people. I like hesitation. I have never seen confidence as a virtue. To be confident in an unnatural situation – I would be somewhat suspicious of such a person. I am terribly frightened of being on stage, to give readings etc. But it seems to me to be quite natural that I should be. To be looked at by two hundred people while you outline your thoughts and feelings and beliefs: it is not normal, and it shouldn’t be. Life is not an advertisement.

You never really did grad school in literature but it’s something seen so important to emerging writing in English. What are your views on this?

I cannot comment on the virtues or otherwise of grad school because I did not attend one. For me reading widely was essential when I was young. A young writer should learn to be alone—that’s important too.

What’s next?

I am working on a new novel set in England.

Text Soumya Mukerji