Author's pic: Michael Lionstar

Author's pic: Michael Lionstar

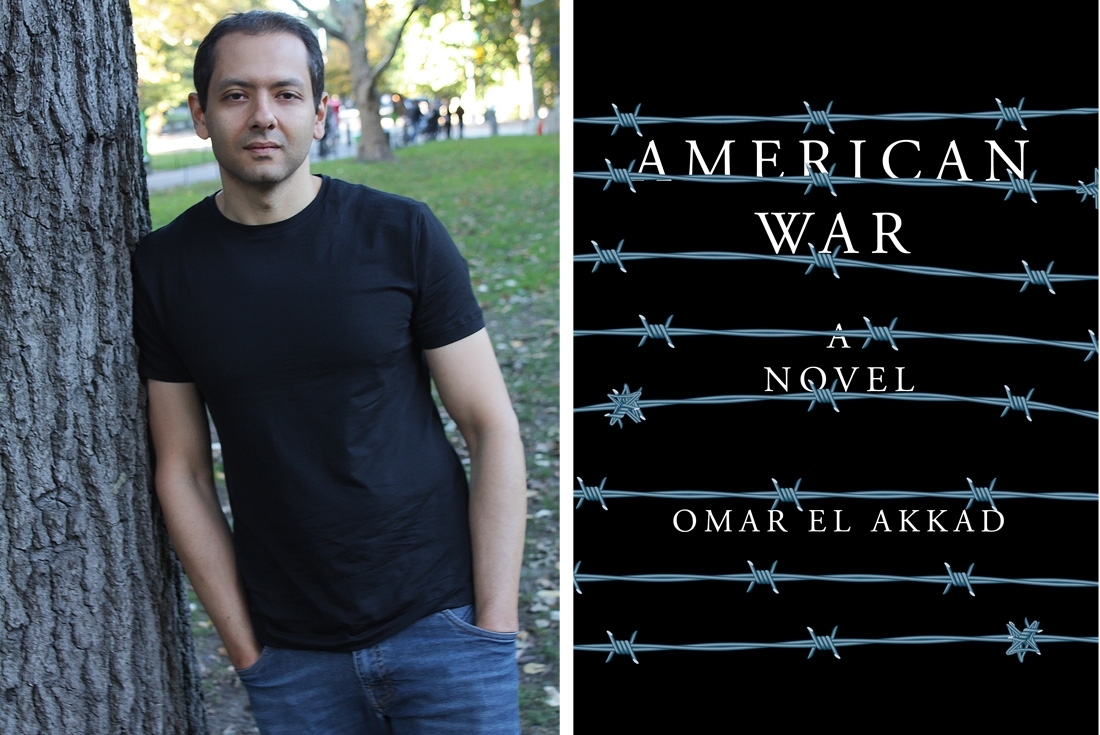

Have you ever met a man who has written four entire novels but decided that only one is good enough to go out to the world? So Egypt-born Omar El Akkad isn’t exactly a debutant, but then he is. Omar’s journey is extremely relatable in some ways and yet his story is brow-raising for its brutality. With American War, the title he has chosen to put out for public reading as a first in fiction, the award-winning war journalist shows a future we must fear.

Tell me a little about yourself and how you began your journey in writing.

I was born in Egypt, and grew up in the Middle East before moving to Canada at age 16. My earliest memories of writing come from the third grade, when I wrote a couple of short poems that made it into the school newsletter [needless to say, the bar for successful submission was not high]. I’ve never been particularly talented at anything, but the realisation, early on in my life, that I could use writing to create and inhabit imaginary worlds came as a revelation. It was life-changing, that power.

In Canada, I attended university and earned a degree in computer science. But I spent most of my time working at the student newspaper and other campus publications [including a decidedly mediocre and short-lived creative writing magazine I founded]. After graduating, I was fortunate enough to land an internship at the Globe and Mail, Canada’s national newspaper. I worked there for 10 years, until I left last summer to pursue a full-time career in fiction. I wrote fiction in my off-hours throughout my 10-year stint at the Globe, and over the years I finished four novels. American War is the only one I felt was good enough to show to the outside world.

What inspired the title?

I remember, long ago, watching an interview with a foreign affairs expert. It happened a few years into the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, and that week there had been protests in Afghanistan against US soldiers. The anchor asked the expert something to the effect of, ‘Why do they hate us so much?’ In his response, the expert mentioned that sometimes, US soldiers have to conduct night-time raids to hunt insurgents, and that during these raids, they often break into the Afghan villagers’ houses and detain the families at gunpoint. In Afghan culture, the expert helpfully added, such things are considered offensive.

I remember thinking, Name me one culture in the world that wouldn’t consider such things offensive. Name one.

If there ever was a genesis moment for American War, that was it. I decided to take elements of all these conflicts that took place so far from the western world, and recast them as elements of a second American civil war. My aim was to advance the argument that cultures, ethnicities and religions might differ, but suffering is universal.

Can you give me a blurb on it?

American War is a story set during the Second American Civil war, which takes place about 50 years from now. Global warming and rising sea levels have wiped out much of the US coast, including the eastern seaboard, and the North and South are at war over the abolition of fossil fuels. The story follows the life of Sarat Chestnut, a child of the southern Louisiana coast, displaced by war. It charts her transition from a curious, trusting girl to, ultimately, a radicalised weapon of war.

This is a very timely book. Did you anticipate the present day political scenario and its impending consequences, perhaps?

I’d love to say I anticipated any of the chaos in the western world over the last year. But in truth, I didn’t. I finished American War in the summer of 2015, a few weeks before Donald Trump announced his candidacy for President. I accept that, given the state of the world, some people will read the book as a kind of attempt at prophecy, but I never intended to write a story about the future.

Can you take me behind your creative process as it occurs?

I have no gift for epiphany, and writing for me is a difficult, slow process. Generally, a small idea might pop into my head, and from this I might construct a scene or the beginnings of a plot, but I almost never come up with grand ideas out of the blue. As such, the first six months of novel-writing for me involve almost no writing at all. Instead, I read, research and collect as much information as I can about whatever topic I’ve chosen. I look for the smallest details of place and of human interaction, the little things people do that so often betray them.

Once I start writing, I tend to split my time between day and night sessions. I alternate between writing [sometimes just a couple of hundred words a day] and editing. I keep a journal of notes as I go, full of ideas for scenes or pieces of dialogue. For the most part, the process is chaotic and incredibly inefficient, but I have no idea how to write any other way.

You have reported widely on war and immigrant turmoil. How do these human conflicts reflect in your book?

Much of what takes place in the book is based on experiences I had as a reporter. The refugee camp in the novel is based on a camp I visited in Kandahar, and the detention facility is based on my experiences covering Guantanamo Bay. But beyond geography, my experiences reporting on various conflicts also informed my ideas about the symmetry of suffering, the way so much of injustice looks and behaves the same. I’ve only ever been tear-gassed twice in my life, once when I was covering the Arab Spring protests in Cairo, and again when I covered the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Missouri. The two experiences are forever twinned in my memory.

Have your roots and your personal history impacted this creation?

Many of the events in the book are, in effect, a repurposing of the conflicts I grew up learning about [or, in the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, being prohibited from learning about. When I went to high school in Qatar, our British textbook had the chapter covering that conflict removed]. The biggest impact my personal history had on the creation of this book is the sense, based on living in so many different parts of the world, that most people aren’t all that different. Our cultures and rituals might vary, but on some basic human level we are all alike.

Between a reporter and writer, which is a tougher hat to wear, and which one is dearer to you?

I find reporting easier to do, but I find writing far more fulfilling. I’m an introvert by nature, and so I function much better when sitting alone in a room than when I have to, for example, try to contact the family of a murder victim for a story. Still, reporting tends to at least come with a roadmap to the finish line. Even investigative journalists working on the most complex stories tend to have an idea of what they want to explore, what they want to find out. Fiction, particularly novel-writing, rarely comes with any such roadmap, and a writer always risks wandering down unknown backroads for miles, with no destination in sight and no idea how to get back home.

What do you think of military fiction in the present day, especially in times of Trump?

I’m sorry to admit this, but I can’t stand most military fiction, particularly fiction about current or ongoing conflicts. When I think of the great war stories, I tend to gravitate to non-fiction such as Michael Herr’s Dispatches, which is one of the books that made me want to become a journalist, or Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie, which is one of the best pieces of reported non-fiction in the last 100 years.

There are a few exceptions. I recently finished reading a novel called Spoils by Brian Van Reet. It comes out in April and is beautifully nuanced. I do think there will be some incredible fiction that will come as a result of our world’s ongoing foray into fascism, but I think most of it will take time. The kind of subtlety good art demands, I think, needs a little breathing room, a little time to recover and assess after all the damage is done. And I don’t think the damage is anywhere close to being done.

What was the toughest part of making this debut? How long was it in the works?

I started the novel in the summer of 2014 and finished it almost exactly a year later. I had no expectation the book would be published, and I wrote it exclusively for myself. It was only several months later, after a bad day at work, that I decided to show it to a literary agent, who was kind enough to take it on. The most difficult part of the process since then has been speaking about myself. I have far less experience being on the receiving end of interviews, and I have no idea how to make the solitary process of writing sound sexy.

What's next?

I’m working on another story. I have no idea if it’s going to be any good, but it’s what consumes my life these days. I’ve been researching it for the past five months and only recently started writing. I hope the end result, if I am fortunate enough to get it published, does right by my readers, and does right by my conscience. Not much else matters.

Text Soumya Mukerji