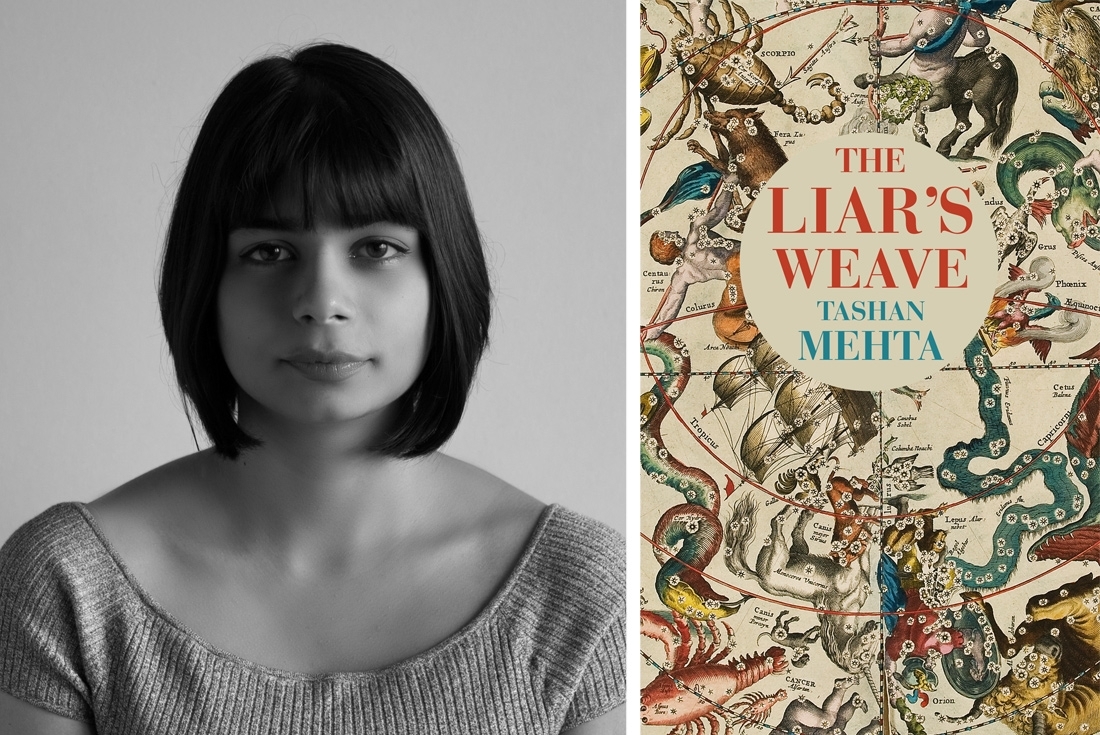

In almost half a year of reading new releases, this is perhaps the strangest plot to come across. Born into a world where birth charts are real and one’s life is mapped in the stars, Zahan Merchant has a unique problem: he is born without a future. This cosmic mistake gives him the ability to change reality with his lies. But there is a catch, of course... .

Tashan Mehta’s debut, The Liar’s Weave, at once leaves you fascinated, intrigued and full of wonder with its vivid imagination. Here’s the journey of this modern work of magical realism.

Tell me a little about yourself and how you began your journey in writing.

I live in Mumbai in Parsi Colony and have an abiding love affair with tea. My journey into writing is predictable: I loved to read and, by nine years old, that grew into an urge to create what gave me so much joy. That urge has seen many forms since then, and was deeply shaken when I chose to study English Literature and Creative Writing at Warwick University. It took the childlike desire out of its comfort zone and showed it what the world was really like: large, passionate, talented and infinitely more varied than I could have imagined. It seemed to have little space for me in it. I walked away and walked back to writing several times after that, but it was my Masters at Cambridge University that sealed the deal. It was a valuable and rigorous year, but also entirely free of creative writing. It made me realise just how much writing had become part of how I interpreted and lived in the world.

What inspired The Liar's Weave?

It was a combination of two threads of thought actually, both born in very different times and places. One occurred when we drew my birth chart at around 13 years old [we’re Parsi, so we were late to the game] and I wondered what it would be like to know the moments of your life before they happened. The second thread was Zahan, born in the second year of Warwick University, as I sat at my desk trying to find a short story idea for a fast-approaching deadline. The character that popped into my head wasn’t Zahan precisely, but he faced the same conundrum Zahan does: the ability to change reality with his lies. I think what interested me at that point is the mechanics of lying, and how the worst lies are the ones we tell ourselves. When I tried to develop that into a novel, it seemed natural to place the character into a known-future setting. I was curious to see where it would take me.

To be born without a future—what a strange, intriguing plot. What does the word ‘future’ mean to you and how did you end up creating a man who does not have one?

‘Future’ is definitely a nebulous term and it has meant different things to me at different points in my life. Currently, it’s more a concept than a certain reality – too much is changing too quickly. But I have always been fascinated with knowing the future and whether that would give you some sort of peace as you lived through the present. The thought naturally throws up the connection between the past, present and future—and that’s a delightfully intriguing thing to play with. Because knowing a future cements a present and reinterprets a past; it locks you in some way. And then a character who does not have a future in a world where everyone does suddenly becomes the powerful one—a turning of the tables. I think what Zahan does in the world of The Liar’s Weave is that he forces everyone around him to reconsider their pasts and redefine their presents. In essence, he makes them ask: what do I want?

“I think what interested me at that point is the mechanics of lying, and how the worst lies are the ones we tell ourselves. When I tried to develop that into a novel, it seemed natural to place the character into a known-future setting.”

Do you think lies may actually have the ability to change reality?

Oh, lies definitely do change reality. We simply have to look at the global political landscape and what the media is transforming into [or the role the internet is playing in our world view] and it’s easy to see, reality is being redefined every second. I read somewhere that the tissue of lies could never defeat the truth [I can’t remember the exact quote]. I’m not sure I believe that. There are so many realities at play, so many subjective constructions of the world, that a singular truth in this fat and solid sense seems questionable. Perhaps I am just young though, and haven’t lived long enough to see truth win out. I do think we can navigate the lies—a constant search for solid ground.

The backdrop of the story, through the 20th century Parsi lifestyle to the land of Vidroha, sounds just as interesting. How did you choose this?

My grandfather used to tell me stories of Parsi Colony when he was growing up: it was mostly all jungle then and it had this heavy, breathing silence. And then my mother took those stories further, talking of how she was kept awake by a tap dripping two rooms away from her, or how she could hear a car five roads down. It stuck in my imagination as a place where everything took on magical proportions. I always wanted to set my novel there, and the political backdrop of the early 20th century helped oil the plot.

Vidroha was harder. I knew it would be in the mangrove forest [which I have always loved for its mirrored visual of twisted roots and branches] but the settlement itself was hard to imagine in a way that fit. I originally saw it as more realistic, hints of which have remained in the final draft. But it wasn’t until I allowed myself to go wild with it—to transform them into a carnivalesque settlement with death puppets and angry revelry—that it really came alive. It seemed the best expression of their hurt and powerlessness.

What is at the core of this book, then?

That’s a tricky question. You hope to create something that interacts with the reader and lives in their mind: I hope it becomes different things for different people. But I am aware that is sidestepping the question, so the honest answer for me would be: powerlessness in absolute power. Human beings have a desire to be more than the sum of their bones, to live beyond and larger than their frailty—so when you’re given that option of absolute power, what choices do you make? What are the consequences? And is what you believe you want really the centre of your desire?

When did you know your first story was ready to go out to the world?

I didn’t. I still don’t. Several wonderful people have helped get the manuscript to the stage it is at now [Indrapramit Das, my editor, being one of them] but if you consider the components of a novel and how connected it is to who you are, all those parts are constantly moving such that there really isn’t an end. A novel is finished when you can no longer work on it, when you feel the limits of your talent in the skin of the idea and know you’ve reached as far as age and time will allow. You do have to let go and see it as an ambering of a moment.

Tell me how your creative process unfolds.

The creative process for this book seemed mostly chaos, but there is a pattern in retrospect. I read a non-fiction story by Hilary Mantel, called Growing a Tale, where she talks about keeping a novel file. She stores snippets of the novel as they come to her, in no particular order—the file format then gives her the freedom to move the scenes around and find a structure. It’s never worked completely smoothly for me, of course, but I love my novel file. I fill it with research notes and paragraphs that appear fully formed in my head, novel threads and character sketches. It holds the chaos together.

What are you currently working on and what is next?

I am currently working on the second novel, which is also signed with Juggernaut. It’s a historical novel set in Udaipur in 1874, so a different setting from the first, but it has its elements of the fantastical—I cannot seem to keep away from them. After this, there is travel: three months around Asia just picking up bits and pieces for the third book. I am very excited.

Text Soumya Mukerji