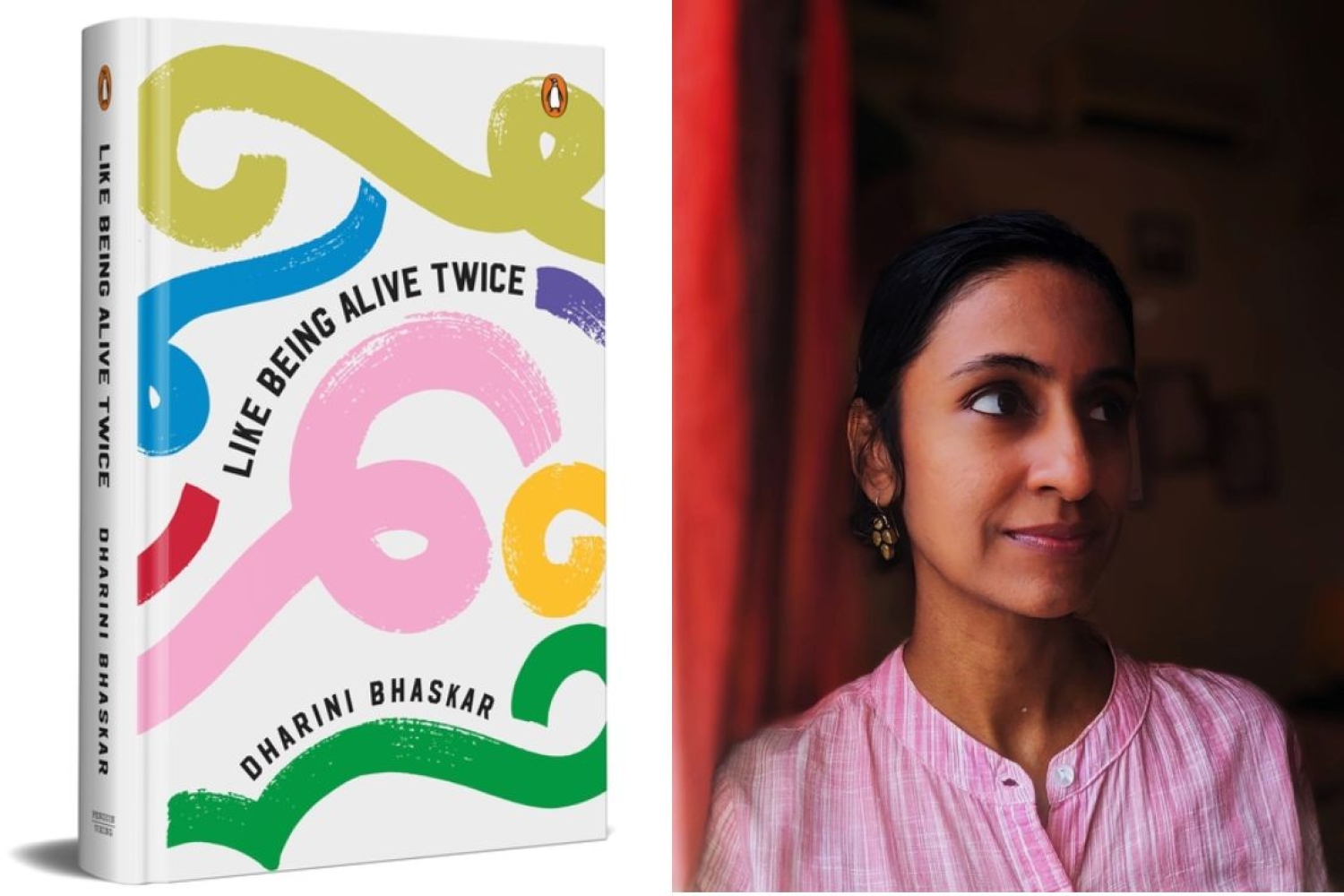

There are two doors in Dharini Bhaskar’s latest speculative fiction, Like Being Alive Twice. One depicts how Poppy’s course of life turned out, while the other paves the way for how it could have been if she had decided to be with Tariq. The novel delves into the possibilities of our existence and how our decisions shape our realities. Life, as Bhaskar aptly puts it, becomes a ‘dance of the dots’. We talk to the author about the challenges, the novel's form, her relationship with writing, and of course, the doors of possibilities.

What prompted the concept of blue and yellow door?

A story, I often feel, is like a pointillist painting; it’s a dance of dots. When I started writing Like Being Alive Twice, I was driven by the desire to see if the story I was building could alter, shape-shift, once I rearranged the dots.

And so it began, the process of following two narrative strands.

The novel opens with Tariq planning to propose to Poppy; with Poppy meaning to say yes. Both of them are fairly certain that they have privilege enough to fend off political blowback in an increasingly polarised state. That’s when the narrative splits in two—one thread conveys all that does happen, the fact that events don’t quite go as intended, that Poppy does not get to say yes; the other conveys what could have happened if Tariq’s plans had fructified, if Poppy had accepted. In other words, the novel imagines, then reimagines, the dance of the dots.

Seminal to the novel is the question: are there moments that open themselves out to multiple possibilities? What if these moments are perceived as having doors? What if we happen to walk through one door? Or another? What then?

And so it emerges, the yellow door—the door the protagonist chooses to open and enter; and the blue door—the door that she could have chosen; the door she missed or ignored or rejected, foolishly or wisely (who is to tell?); the door that could have changed everything for her.

But could it have really?

So, what also haunts me is this—whether the ‘doors’ we enter or exit can actually alter our destinies.

What were the challenges of writing speculative fiction?

To be honest, when I set out to create Like Being Alive Twice, I did not intend to write speculative fiction. I simply had a story to tell, and it was a story within which there nested possibilities. I wished to trace each one. Along the way, the book seems to have stumbled into a genre. The categorization of the setting as ‘dystopic’ is also intriguing. Largely because the times we live in are anyway dystopic. Nothing we imagine or build or tell can startle or give the reader pause. Nothing holds within it a nightmarish tomorrow—not anymore. We are inhabitants of that nightmare today, a nightmare where glaciers melt, and lands grow parched, and walls emerge, and people give up on people.

Literature, at best, reflects this, grants it a vocabulary, articulates what isn’t articulated strongly enough or clearly enough. It makes personal what may otherwise feel distant. As for the challenges I confronted while writing a book, I think they were similar to the challenges I confront while writing any story: the tyranny of the blank page, the battle with time, the struggle to find the perfect word . . . And then, of course, all the rewriting.

What is your first memory of writing and do you see any slight influences of it in this book?

I don’t quite have a first memory of writing. But I do know I started engaging seriously with the craft in my late teens. Back then, as is true now, I was a follower of poetry, but I couldn't bring myself to write it—I was (and remain) too much in awe of the genre. So I attempted writing something that hovered in-between, that carried neither the certainties and expanse of prose nor what Arundhati Subramaniam speaks of as the ‘suddenness, [the] distillation, [the] toxic shock clarity, [the] verbal single maltness’ of poetry.

It was an attempt—though still flailing, still trying to arrive at a voice, a form, an identity. I am very glad to say that much of my early writing is lost. But what I think the process taught me, and continues teaching me each day, is this: that the word is sacred. That we must approach it with reverence. And if we are especially fortunate, on those rare nights when the moon is full and the hour is magicked, we get to inhabit the word. I guess we write for such moments—when we are allowed access into the portals of language, when we are granted the right to know the word in the marrow.

What do you hope for readers to take away from this book?

I don’t know. A reader is a pilgrim, after all. And a journey through a book is a journey of faith. What I mean is, the journey is meant to be individual and specific, shaped by the pilgrim’s histories and desires. The destination cannot be dictated by me. If I’m lucky, I will get to learn of each reader’s passage through the book—the treasures she carried, the burdens she left behind.

Here’s what I hope, though, that anything I write will do: I hope it will make the reader fall in love with the written word. I hope it will compel her to buy a book of poetry, be it Linda Gregg who has inspired the title of my novel, or anyone else who engages with the form with commitment and awareness and passion. Most of all, in the instance of this specific novel, I hope the reader will see, with greater precision, the world we occupy, the one each of us has unwittingly or with deliberate intent built. This world asks desperately to be dismantled and rebuilt.

The novel runs backward and chews over the decisions that the narrator makes, what made you write in such a form?

As Jeet Thayil said, a novel, by its very name, suggests that it is attempting something new. To that extent, it’s worth asking—is it the linear narrative (with predictable storytelling elements or familiar linguistic patterns) that steers away from the spirit of the novel? When I started working on Like Being Alive Twice, I knew I wished to study a moment that opened out, that revealed two paths. I knew I wished to follow both the paths, bear witness, chronicle the things they held, the bounties, the simmering unrest, the devastation, and maybe, perhaps, was-this-even-possible, a distant shimmer of hope.

Given that I had two stories, linked yet discrete, to trail, I suppose it was inevitable that the narrative would assume the form it did, with alternating chapters. As with child-rearing, so too with storytelling: one must learn to surrender. One must surrender to the wisdom of that which is before us; to trust and be willing to get surprised.

The story knows.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 22.03.2024