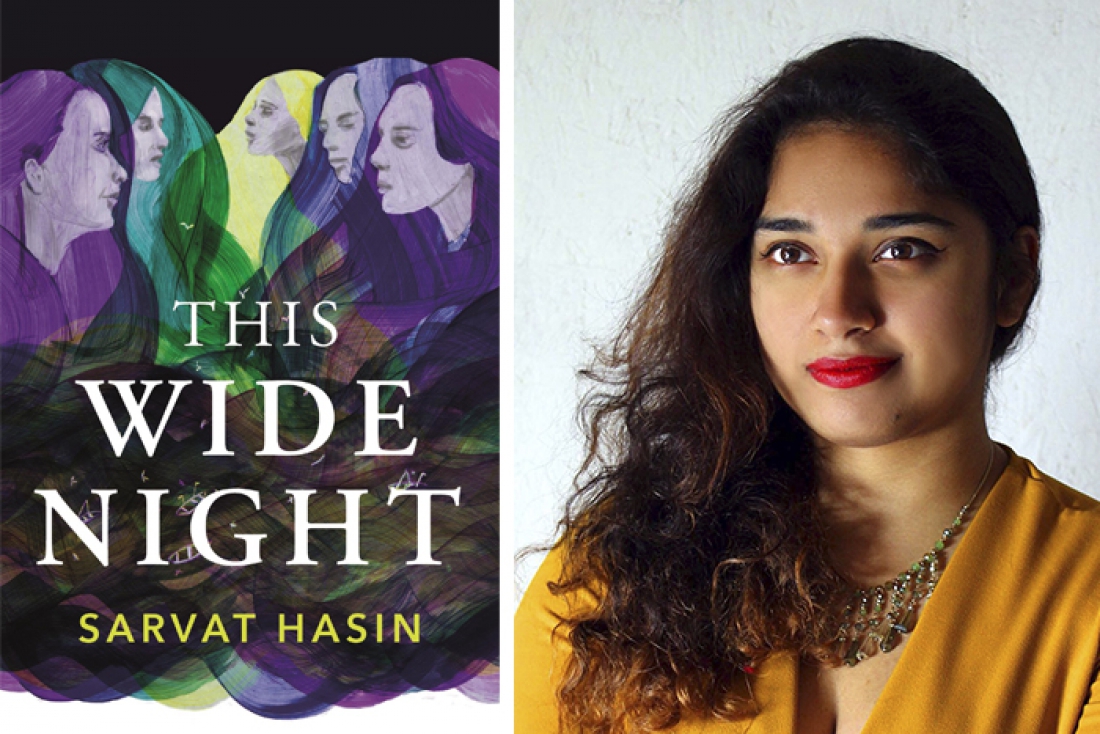

Sarvat Hasin

Sarvat Hasin

The girls came to me first. The book ends in Manora, a not-quite island off the coast of Karachi that I visited with a friend as a teenager. I remember how isolated the beaches were there, completely different from the ones in the city, even the private ones. It felt like the end of the world. The characters were born out of that setting, people who would choose to live apart from society. In a city as thickly populated as Karachi, this feels impossible. I got the structure of the family and their next-door neighbour, Jimmy, from Little Women. I always liked Laurie and his fascination with the March girls. My editor and I often talk about this book being a halfway house between Little Women and The Virgin Suicides; the family dynamics of the former infused with the langour and dreaminess of the latter.