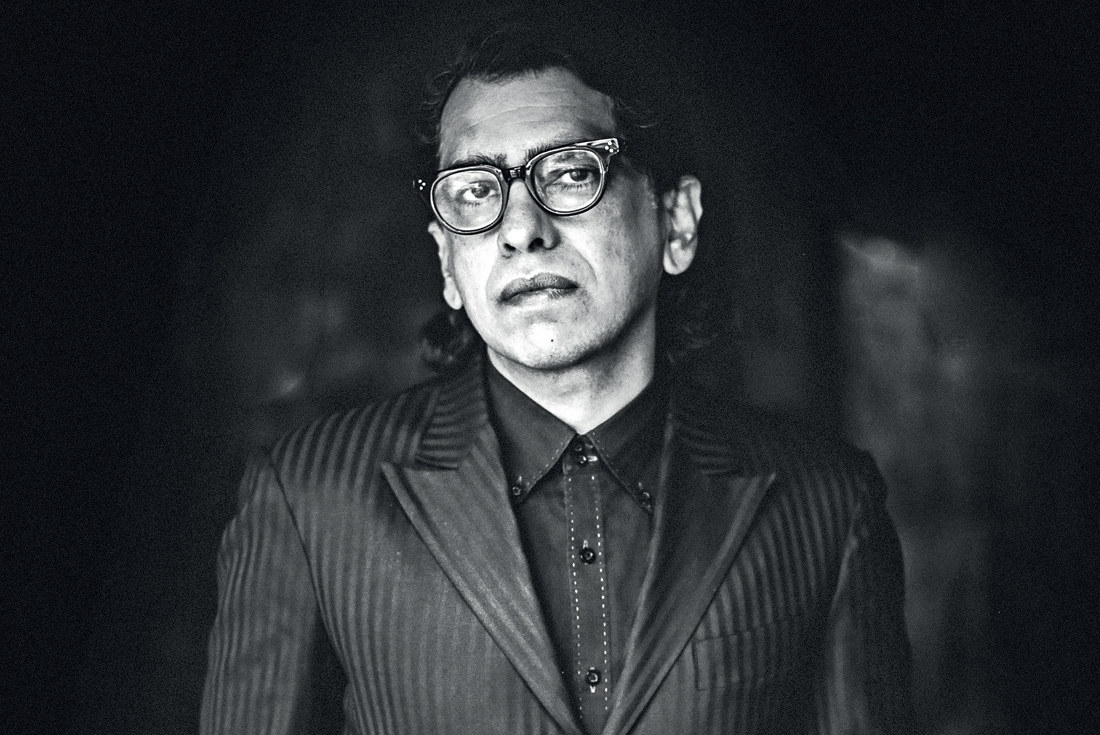

Photography by Emily Winiker

Photography by Emily Winiker

World music needs intervention. The category, as expected, should have pushed new cultures forward through music. Instead, it perpetuated the exotic-ization of non-Western traditions and slotted them into stereotypes. ‘It groups everything and anything that isn’t “us” into “them.” This grouping is a convenient way of not seeing a band or artist as a creative individual, albeit from a culture somewhat different from that seen on American television,’ David Byrne of Talking Heads said in the late ‘90s.

Byrne wasn’t the only one who noticed the futility of a world music category. Nusrat Durrani has centered his career on rescuing and redefining this concept of global sounds. In his mid-thirties, he traded a successful career in an automobile company in Dubai for the instability of a career in music. Spurred in part by David Bowie’s unconventional (at the time) Let’s Dance music video, he packed his bags and showed up at the MTV office in New York. Two decades later, he is the Senior Vice President at MTV World. Driven by his faith in the power of music to serve a purpose beyond entertainment, he is committed to initiating cultural exchange through music that mirrors local traditions, emotions and causes. From obscure sub-genres to barely known artists, Durrani is neither bound by a country nor restricted by genres. He has a radar that spans the globe for new-age sounds and he has a platform to present those sounds to a worldwide audience.

In a black suit and white shirt, offset by pale grey sneakers that were designed to look worn out, Durrani is every bit the music media guru that he is expected to be. A string of plastic masks—animal heads with cut-out eyes—are laid out on the windowsill behind him in his office. Overlooking the swankiness of Hudson Street in lower Manhattan, the masks seem indicative of a vibrant world beyond the brick-walled streets of the City—a world that he continues to bridge and bring closer through music. His recent initiative, Rebel Music, successfully zoned in on music emerging from countries battling social injustices.

As he sat down to recount his experiences in the industry, his vision for global issues and pop music became evident.

You tapped into your life savings and went after your dreams at an unexpected time in your life. Was it an impulsive move or did you always want to be associated with the music industry?

Growing up in India, I was peculiar. I was an outsider to the culture in some ways. I’m very much a part of the Indian cultural fabric, but growing up in a relatively small town, I was surrounded by conventions I didn’t necessarily relate to. For instance, the need to become an engineer or a doctor or get into the IAS. I went to La Martiniere [Kolkata]—a French-British school with a gothic medieval building; the whole environment was strange. I had the mindset, I didn’t realize it then, to be rebellious. I had things in my head that I didn’t see around me. In Dubai at the time, I wasn’t a teenager. I was a fully developed individual and I asked myself: Am I going to do this for the rest of my life? As much as I might be good at this, is it really what moves me? No. It doesn’t. Music and connecting cultures moves me. Music was the spark for me and watching MTV propelled me at the time.

You were raised in a traditional family in Lucknow. How did they react when you decided to move across continents in pursuit of an unstable career?

My family was appalled. First I didn’t become a doctor, then I left India for Dubai, and then I wanted to go to the United States on a whim. My parents didn’t talk to me for two years.

It took a ton of courage and years of perseverance for the risk to pay off. How would you describe that journey?

It was like diving from a plane without a parachute. There was a foolish fearlessness in me. To me, failure wasn’t an option. I just had to do it. I’m very fortunate that I went on a journey—that’s the most important thing. I don’t think it was particularly hard, thinking back now. When I was going through it—often times I thought: ‘What am I doing?’—I put everything at stake, pissed off my parents. I didn’t even have a job for a year, what was the end game?’ There was uncertainty and doubt, but you just had to plough through it. People like to hear that it was very difficult and that I had to overcome a great obstacle—like studying under a street light—but none of that happened. Inventing yourself in a different country is very difficult. But relatively, people who come here with nothing, who work at gas stations or clean streets or are unemployed for many years, or smuggled themselves into America in containers—that’s difficult. The kind that I encountered, is softer. I had a net to fall into. I could go back to India. I had an education and the means to come here. It’s not been that difficult.

But I would answer that differently, too. When I came here, I had a very nuanced understanding of America— or so I thought. You know, we’ve seen it all on TV, watched the films, read about it in books. We have our heroes. But, the thing I was naive about was that America or New Yorkers, in particular, would know as much about us. And that wasn’t the case. I went into reverse cultural shock. People didn’t know where Dubai was and they were surprised I knew so much about American music. I was like, ‘What’s so surprising? This is what I grew up with.’ The time that I came here to create a career in media was when not a lot of Indians were in the media—that was difficult. It was hard to be taken seriously. They were like, ‘How can you, someone who didn’t grow up here, tell us about our stuff?’ So yes, there was hardship. I wasn’t trying to just do a job, I had to create stuff and make my own path. It’s never easy when you go against the grain.

What did you set out to do? What is your vision for music and how do you perceive its impact on cultures?

I’ve been listening to music forever. Music is about dreaming, travelling and imagining. It’s all about connection and therapy. However, in my professional life, I’ve realized that music has great power. It’s a connective tissue. It’s something that can make you transcend your differences. The power of music to catalyze change and bring people closer, I’ve realized over time, is beautiful. I’ve tried to centre my career around that. Not in a touchy-feely, let’s hold hands and sing Kumbaya kind of way, but to be able to understand or open up to somebody else’s song, even if it’s in a different language. America, and the West in general, has exported its culture to the rest of the world all this time. But does America know about the icons in India? To me, that’s a problem, but beyond that, it’s an opportunity. As Americans, we need to open ourselves to the music of the world. We’ll be able to understand music and culture differently.

Has that changed since you first set foot in the industry?

Absolutely. In my 20 years in this company, it’s changed profoundly. There was a time when I used to talk about K-pop. Not everyone would like it, but it was a whole other take on music. People were like, ‘No, it’s such a novelty; it’ll only be popular in Asia because it’s in Korean.’ But PSY changed that. He wasn’t singing in English, then why did it become the most popular video ever? And now K-pop is huge! And people know Bollywood—although, it doesn’t represent Indian culture completely at all. It’s because of the social and digital media. Music is now cross-border and there’s no stopping it. We’re getting into a period where you can access music from any part of the world and in doing so, something will change in you every time.

People are also travelling now as tourists or students and they bring culture with them. The world is a smaller place. All that is good because everyone is a little ambassador of their own culture. Also political events—9/11 is one of the biggest tragedies in this country, but it forced us to look at things differently and acknowledge that there is a world outside that we must pay attention to. Like a lot of the revolutions in Egypt and Mali or Russia—music is at the heart of it. Music as a tool of dissent is more prevalent because of technology.

Did this idea of music and revolution lead to Rebel Music?

As someone who travels around the world, I was very moved by the notion that there were musicians at the heart of many movements. There was an opportunity for us to create a different vision of say, Egypt. In the U.S., most people didn’t know much about Egypt. They knew there was some political unrest happening there. On TV there were people telling you what’s happening; there were people shouting and killing each other. But you never heard from the youth of those countries or knew what was really going on there. At the heart of those rebellions were young people— particularly musicians, fighting against status quo. I felt if we could articulate that into a language that the youth understands, we might come away thinking more empathetically about Egypt than what was being shown. If you see a young person, you start emoting differently. On TV, all that you see about Israel-Palestine for example, is hate hate hate. Yet, there are other stories to be told. There are musicians on both sides of the struggle collaborating and working together and presenting their stories which is more important.

Was there a musician in particular that cemented this idea?

I was in Egypt right before the first revolution happened and I met a lot of young people—musicians, activists, artists. Something was brewing. I felt this crazy energy. They even spoke of rebellion and writing songs and creating artwork. I came back mystified and inspired. I didn’t know what it was leading to. Then a few weeks later, there was the revolution. When I saw it through the lens of CNN and other mainstream media, the narrative that was unfolding was so different from what I saw there. Rami Ahsan is a young singer-songwriter whose story I read. He was not particularly known at the time, but was very much a part of the revolution. His song became an anthem for the revolution. He was rounded up and beaten and tortured. But he came out and went straight back to Tahrir Square and started singing. Why would someone so young risk their lives? I was profoundly moved. There are so many others like him that I felt the West media should hear about.

The role of technology was widely reported in that particular revolution. Social media has changed the way we communicate and it has brought about an unprecedented awareness of the world. Yet, there are those who believe the impact is not entirely positive. How would you describe its impact on music, in particular?

Technology has definitely benefited music. In terms of discovery, it’s fantastic—there have been Pandora, Spotify and MTV platforms. It’s a great time to discover music from around the world. But also, music technology has enabled a lot of young artists to bypass traditional distribution and production and put stuff out for people to hear. There is more music being made now than ever before because people are empowered to create, share and even sell it. As someone who is passionate about music, it’s the best time ever. I’m a junkie, I need a fix and I can always get it. If there is a downside, it’s the same thing—because technology lets you create content so easily, it also puts a lot of crap out there. You can’t stop anyone from doing that. There is a lot of music being made that shouldn’t be made. But then the curators of music start playing an even bigger role, so you need to go to trusted sources. You want a source that will contextualize it and tell you a bit more.

Your vision and efforts as a curator continue to highlight the power of music. Do you think music could have an even greater impact or have we realized its potential?

I think the role of music is still not fully explored or exploited, particularly in diplomacy and creating bridges. I wish we gave ourselves more to that idea. I truly believe the world would be very different. The media is to blame for the way we’ve shorthanded some countries and their music. The notion of ‘World Music’ is a very redundant and obnoxious idea because it stereotypes—like playing the sitar and tabla is considered Indian. But it’s so much richer than that! In my opinion, World Music is a bad label. The frustration I have is this ghettoization of music.

What do you think of the music coming out of India?

India in general, is probably one of the richest countries for what it has and represents. I’ve been to many places, but nowhere will you find the same depth of culture. We could keep mining it forever and we would never run out. But we’ve let ourselves be lobotomized in some ways. We’ve been hypnotized by Bollywood. I don’t have any problem with it; some of the finest films I’ve seen come from it, but it’s not Indian cinema. That would represent some of the best art films and independent films and cutting edge films, but no one knows the country for those. The industry is much broader and the nation is missing out on that cinema. That has also impacted music—Bollywood music dominates the country. Where do independent musicians fit into all this? The industry is centered around it, so it’s hard to play gigs, get recording contracts and get an audience. Young musicians are doing incredible stuff there. I wish we heard our own musicians with greater care rather than have this hunger for everything coming out of the West. I did that too, but there’s so much coming out of India. We have some of the biggest treasures that remain undisclosed. But, that is changing now, with technology and travel and openness. People are going to concerts and listening to their own people. There’s a future and it’s going to happen.

In retrospect, do you think New York aided your success in ways that India couldn’t have? Could you have followed this path back home?

New York is very special. This is a city without judgments. Forget about the fact that it’s the world capital of media, music, etc. The standards are highest across the board. But, the greatest luxury of inventing myself in this city was that no one was judging me for my success or failure. Back in India, the judgments were very severe at the time. If your son or daughter didn’t become a doctor or an engineer, they were deemed to fail. Things have changed now, but back then I would have had to destroy myself to invent myself. But now, people are doing it. Vijay Nair of NH7 is so young, but he is following his dream. Ten years ago, who would have thought that creating a successful business around festivals would be possible? I think every young person embarking on a career in music, even now, is brave. But can they do it now? Absolutely. There are unprecedented possibilities.

Our conversation with Nusrat Durrani was first published in our Music Issue of 2014. This article is a part of Throwback Thursday series where we take you back in time with our substantial article archive.

Text Mona Lalwani