I am lucky to meet Hans Ulrich Obrist, one of the most celebrated curators of contemporary culture and the artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries in London, early one morning in Delhi. He has not yet had his coffee but he is wide awake to the future and already brewing it.

Consistently ranked among the art world’s most influential figures, he is a critic, historian and author who defies time; the man behind the ‘Brutally Early Club’ of salonstyle breakfast meetings with artists and thinkers, curator of over three hundred exhibitions worldwide and conductor of two thousand four hundred hours of interviews with creative minds. His authority is as disarming as his childlike curiosity.

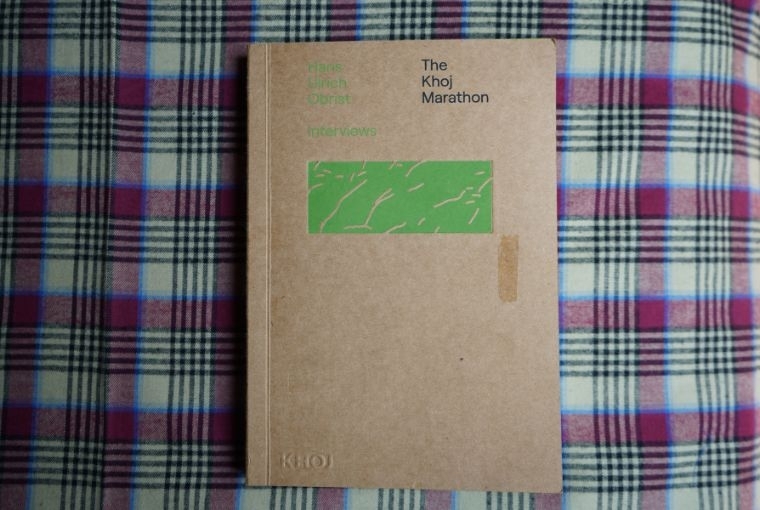

With the launch of The Khoj Marathon interviews, a collection of his conversations that took place in 2011 with twenty six prominent Indian cultural voices, we get into a dialogue that seamlessly straddles art, movement, time and interconnectedness.

Can we begin by going back to a childhood experience that continues to influence your practice today? How did your upbringing shape your creative inspiration?

Growing up in Switzerland, there were lots of experiences which brought me to art. I grew up in a household where art, in general, didn’t play a role, so art came to me through unexpected trajectories. First, it was through the artist Hans Krusi, who sold flowers and his drawings on the streets of Zurich. He was also in commune with nature and a worker on a farm. A second encounter with art was through the timetable of the railway stations in the analogue age. Then, walking with my parents, I would see the work of the famous ‘Sprayer of Zurich’, Harald Naegeli. Another example is Emma Kunz, a spiritual artist with amazing power, who also discovered the healing quality of a rock – AION – which we had in the house. I think that’s also why I believe that we need to not show art just behind doors, we need to go with art into society, to disseminate art. Because if that would not have happened in Switzerland, art would not have arrived to me, growing up in a family who never went to a museum, right? So I think that’s where my belief about the democratisation of art, making art more accessible and removing the guards, comes from.

Movement has been at the heart of your practice. Since the age of sixteen—you’ve never really lived at one place. Does a shift in space then translate to a shift in perspective? What is your idea of home and centredness?

I think it all began with night trains. And I still spend a lot of time on trains in Europe, because you can basically go anywhere by train. I think it was always this idea of being in the middle of things, as (French philosopher) Gilles Deleuze once said, but in the centre of nothing.

And I grew up near a monastery town. My parents didn’t take me to museums but they took me to a monastery library. And I realised that the monks who lived in this monastery in the Middle Ages would migrate, they would somehow gather all the knowledge and then carry that knowledge to the next place. The idea of having this kind of exchange of knowledge stayed with me. Everything I do, grows out of studio visits and conversations with artists of all disciplines and that’s really important as it sort of liberates time because I think we live in a very accelerated age.

And also think it’s simply about the idea of making junctions. I think my job, as (author) JG Ballard told me, was making junctions. So in that sense, it was always necessary to travel. But I did, always, have a base. I was initially based in Switzerland, and then started to travel by night train all over Europe. Then quite early on, I got a grant from the Cartier foundation. And then based on that, I got a job in Paris at the Musee d’art, which was a very unusual job called the Migratory Curator. In 2006, I moved to London. And now, I’m kind of between London and Switzerland. So I would say that I’ve always had one or two bases, it wasn’t that I was completely nomadic.

Your Khoj Marathon Interviews probes creative minds across contemporary culture. What is the secret to a great interview? How do you foster lateral thought in your inquiries and what sustains your interest?

I think it goes back to your previous question because very often, the conversations connect to previous conversations, so in a way, there is a whole memory and archive of previous conversations. It’s very much laterally connected because it often has ramifications to what other artists thought of me. It’s also why I always ask this question about the unrealised project because I’m interested in this idea about ‘how can I be useful to art?’ So in that sense, these are not only interviews, they’re conversations about doing things together, sometimes a book comes out of it, sometimes an exhibition comes out of it, sometimes something totally different comes out of it. I would say that the question of the unrealised project is always at the centre because I’m very curious what practitioners haven’t been able to do in the framework of the existing institutions and what we could actually do, how sometimes such projects can actually happen only if we shift a little bit.

It’s about going beyond the fear of pooling knowledge and bringing fields together. Very often, even within a city, different fields or disciplines don’t talk to each other. I have always felt that we need to instigate these junctions or connections. In 2008, I conducted research in India with Julia Peyton-Jones on what later became a travelling show called the Indian Highway at the Serpentine in London. We worked with Indian artists and architects such as MF Husain, Tayyab Mehta, Shilpa Gupta, Dayanita Singh and Raqs Media Collective, so it was very trans-generational.

And then soon after, we did the Khoj Marathon Interviews in Delhi, bringing generations together. It went from (India’s first female photojournalist) Homai yarawalla who was ninety nine when we did the interview, to much younger artists like Shilpa Gupta, who was just starting out then. What happened in Delhi in a little pavilion in a park was beautiful. I live in a park and work in a park every day, so (curator, director) Pooja Sood at Khoj, who was aware of my interest in pavilions, arranged for a meeting with these twenty six artists outdoors. We had these infinite conversations in the park. And looking at the book, it’s still kind of crazy to imagine that it was all in one day.

I also visited artist Arpita Singh and that sort of planted a seed, which now, fifteen years later, leads to a show. We’re doing a retrospective of her work at Serpentine, which stands for pioneering artists whose work hasn’t had the visibility it deserves. And Arpita Singh has never had a really big solo show outside India. So, it’s not only looking at the past, you’re looking to the future. It’s about producing new knowledge. And the research goes on, I’m back here (in India). It’s very much an infinite conversation.

You have often spoken about ‘liberating time’ and going beyond traditional schedules. Can you elaborate on your relationship with time and contemporaneity?

As (Erwin) Panofsky said, the future is invented with fragments from the past. And yet, I’ve always had a curiosity for what we call the ‘extreme present’. I believe that we need to support artists at the beginning of their trajectory and that means doing research to see how artists work with new formats. Because when I was very young and got a grant from the Cartier foundation, it was a life-changing experience to be part of a very interdisciplinary program at twenty three.

And in terms of liberating time, I think there has also been some biographical aspect, because when I was six or seven years old, I was involved in a street accident with a neardeath experience. I think that also changed my relationship with time. There was a certain sense of urgency installed through that and maybe a feeling that we needed everything done, to make days very productive and maybe also expand time and not follow the clock.

“Everything I do, grows out of studio visits and conversations with artists of all disciplines and that’s really important as it sort of liberates time because I think we live in a very accelerated age. ”

You have consistently pushed the boundaries of where and how art is presented. As a believer in interstitial intimacies, and modest, migratory museums, do you feel the expression of art as formal exhibitions can stifle the essence? What untapped opportunities do you see?

We still need protected spaces for art. It’s not that I want to abolish museums. I love museums and I love exhibitions. But I believe that it’s not enough that we show art only in these white cubes. I think it’s really important to connect the galleries to the park in the spirit of the commons. This is also why we have free admission (at the Serpentine). Visitors can come to the gallery as they come to the park; it’s freely accessible. And then to go from concentric circles into the city and create experiences with contemporary art on billboards, on taxis, in the subway in many different ways. So I think very often, an exhibition is about constructing such an archipelago of lots of different interfaces and bringing to the museum people who wouldn’t come otherwise. And I believe in this idea that we actually create a web of relations in the city and that we also go into neighbourhoods which wouldn’t necessarily have connected with contemporary art.

This year’s Serpentine Pavilion marks the 25th anniversary of the prestigious annual commission. It’s interesting that you chose Bangladesh-based architect Marina Tabassum…

The more I worked with different disciplines, the more I started to be invited into the field of architecture, because I bring architecture into the art world. And based on that, we then decided ten or twelve years ago to open up the pavilion for a younger generation of architects. And of course it proved to be really efficient and also exciting; creating a very positive energy and a lot of visibility.

And so we’re very excited to now work with Marina Tabassum, with whom for the first time, we’re doing a horizontal pavilion on the move.

The world presently stands at the cusp of a convergent cultural revolution catalysed by digital connectivity. As the original ‘junction-maker’, what are your views on this important phenomenon fueling creative change globally and the need for interdisciplinary institutions?

On the one hand, there’s a huge potential and at the same time, there are also limits to it, which of course happen through the ‘filter bubble’. As (tech expert) Eli Pariser points out, there is very often a lack of dialogue because people get locked into the algorithmic ‘filter bubble’. And my friend Etel Adnan, the poet, always said that the world needs a common future and not isolation. So that means we need to go beyond this ‘filter bubble’ because it narrows the spectrum.

I think a lot of artists today use technology to find ways of togetherness. I think the other thing which is important, as the lockdown also showed us, is that we very urgently need spaces where we can come together. So I think the question is also, ‘how can we provide public spaces where mixed reality experiences can take place?’ as would be the case in the future.

And as (German artist) Rosemarie Trockel told me, we need to protest against forgetting, and go and see artists who might not be on the Internet – pioneering artists who have not got the visibility they deserve. The homogenised form of globalisation can also make things disappear, languages disappear. That’s also why my Instagram celebrates handwriting. And I think that’s also what artists can do using technology – resist the homogenising force of globalisation.

But then (Édouard) Glissant predicted as early as the seventies that these forces could also provoke a counter reaction. And that would be new forms of localisms, or nationalisms, which we can observe everywhere now. And that of course means that there is a lack of tolerance, which is a big problem – to think that our roots are more important than others’, and we can somehow allow ourselves to oppress those. That’s why Glissant said we need to resist both tendencies. And so, I think that in the 21st century, it is important to find this Mondialité, this balance and celebration of being open for a global interdisciplinary dialogue, listening sometimes also to languages we don’t understand.

“In the 21st century it is important to find this Mondialité, this balance and celebration of being open for a global interdisciplinary dialogue, listening sometimes also to languages we don’t understand.”

What is your biggest learning on the curatorial journey? ‘Curation’ has turned a major buzzword today – how would you define distinctive curation?

I’ve learned a tremendous amount from outside the art world, I told you about Glissant, (Fernando) Pessoa, Etel Adnan. The part of the curator in French is ‘commissaire’ and that’s like police language. There is something very top-down in that profession. I’ve always been interested in undermining that, or opening it up to the idea that it’s not all top-down but also bottom- up. And that came from (Hungarian French architect) Yona Friedman. I am also always learning from artists.

I think what has changed over time, as you say, is that the notion of curation has become much more expanded. Cafes are being curated or shop windows are being curated, all of that. But I’ve anyway thought we might need a new language. I’ve always used this idea of junction-making, so that’s a form of curation. I make junctions between objects I install in a show. I make junctions between artists who often don’t know each other. I make junctions between art and other disciplines. We can only understand the forces in art by making junctions between people, between disciplines, between objects.

For instance, there’s the quasi-object. Say a football – you look at the object, it’s basically meaningless unless you interact with it. But then a whole ritual is built around it. The whole game is built around it. And a lot of artists are interested in quasi-objects. And then there is also the hyper-object. (Philosopher) Timothy Morton thinks of hyper-objects as the weather, bigger systems. So, in that sense I’m a junction maker of people, of disciplines, of objects, of quasi-objects, of hyper-objects and of non-objects.

How can emerging technologies enhance creativity without compromising it? Can artificial intelligence and artistic intuition form a harmonious partnership, in your opinion?

There are so many examples of the collaborations between artists and technologies, like recently an interspecies garden by (artist) Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg in creative collaboration with AI, where she created a garden for pollinators. It’s a garden not for us humans to enjoy but it’s for the bees, butterflies and other pollinators in the spirit of natural empathy. So, AI can actually contribute to positive environmental impact.

What upcoming projects excite you the most?

Many parallel realities. A bit like in (British physicist) David Deutsch’s book, The Fabric of Reality published in 1997. First of all, the ongoing experiments in art and technology, which we do at the Serpentine, are exciting. We’re working on a new video game with (artist and game designer) Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley.

There’s also the ongoing evolution of my solo show, WORLDBUILDING, which will tour Asia and the US in 2026. I’m also excited about a forthcoming artist show at the Serpentine summer exhibition in connection to environment and ecology, where (Italian sculptor) Giuseppe Penone will connect the Serpentine with trees and bring the trees into the gallery, the galleries through the trees. It will be an exhibition both in the park, inside and outside, very much about the community with the environment.

Besides that, we also have a series of shows by very well-known artists with a very unexpected angle. We’re going to have Peter Doig, a well-known painter who has been passionate about music for a long time. And I’ve always been very interested in curating sound. I think there is a missing sonic museum in the world with multi-dimensional sound installations.

I’m excited about the first chapter of an autobiographical book which I wrote during the lockdown, called A Life in Progress. And about this idea that we need a Black Mountain College for the 21st century, how we can actually think about new interdisciplinary schools.

Words Soumya Mukerji

Date 18-10-2025