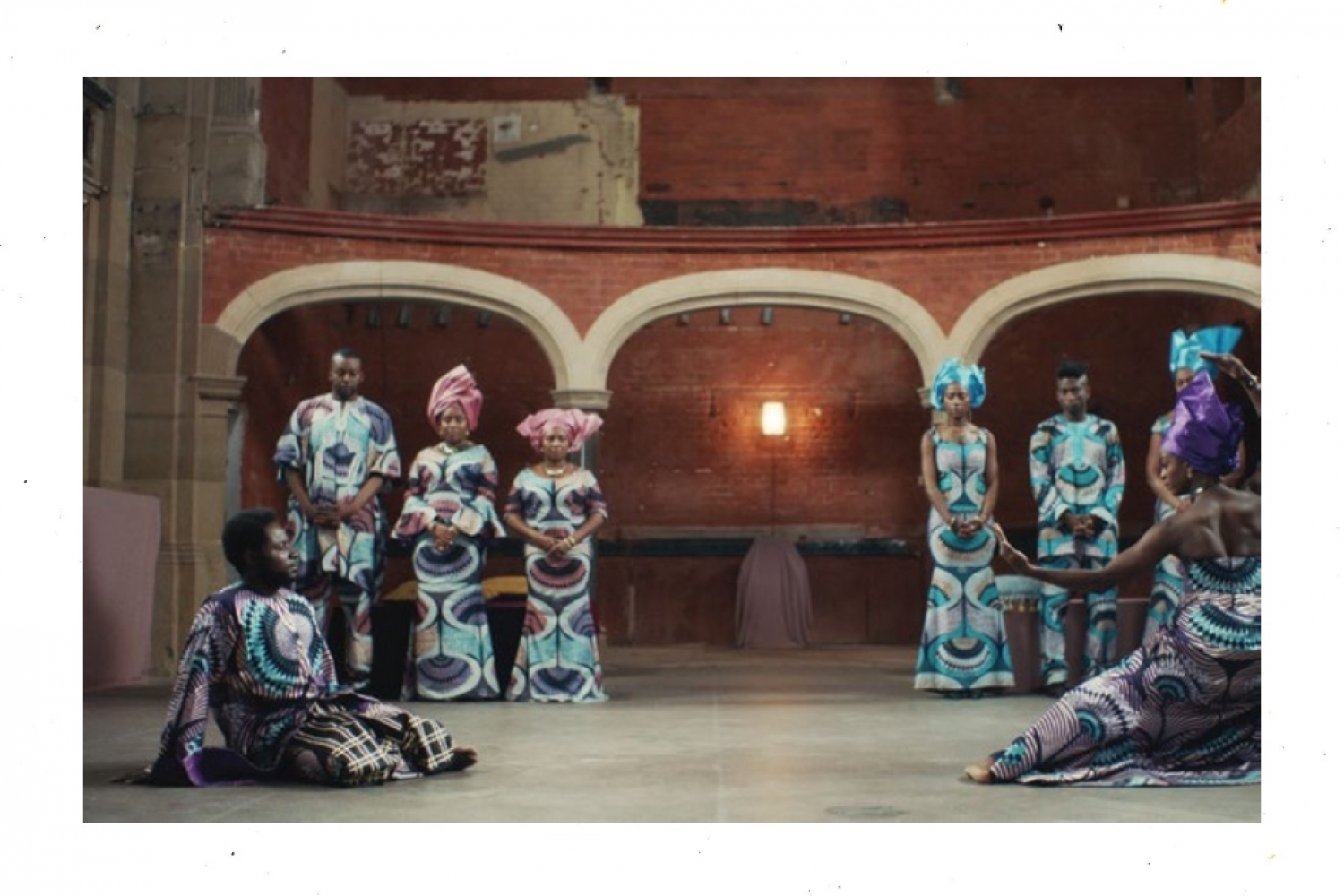

Don’t Look at the Finger (2017) by Hetain Patel. Still pho- tographer Nick Matthews.

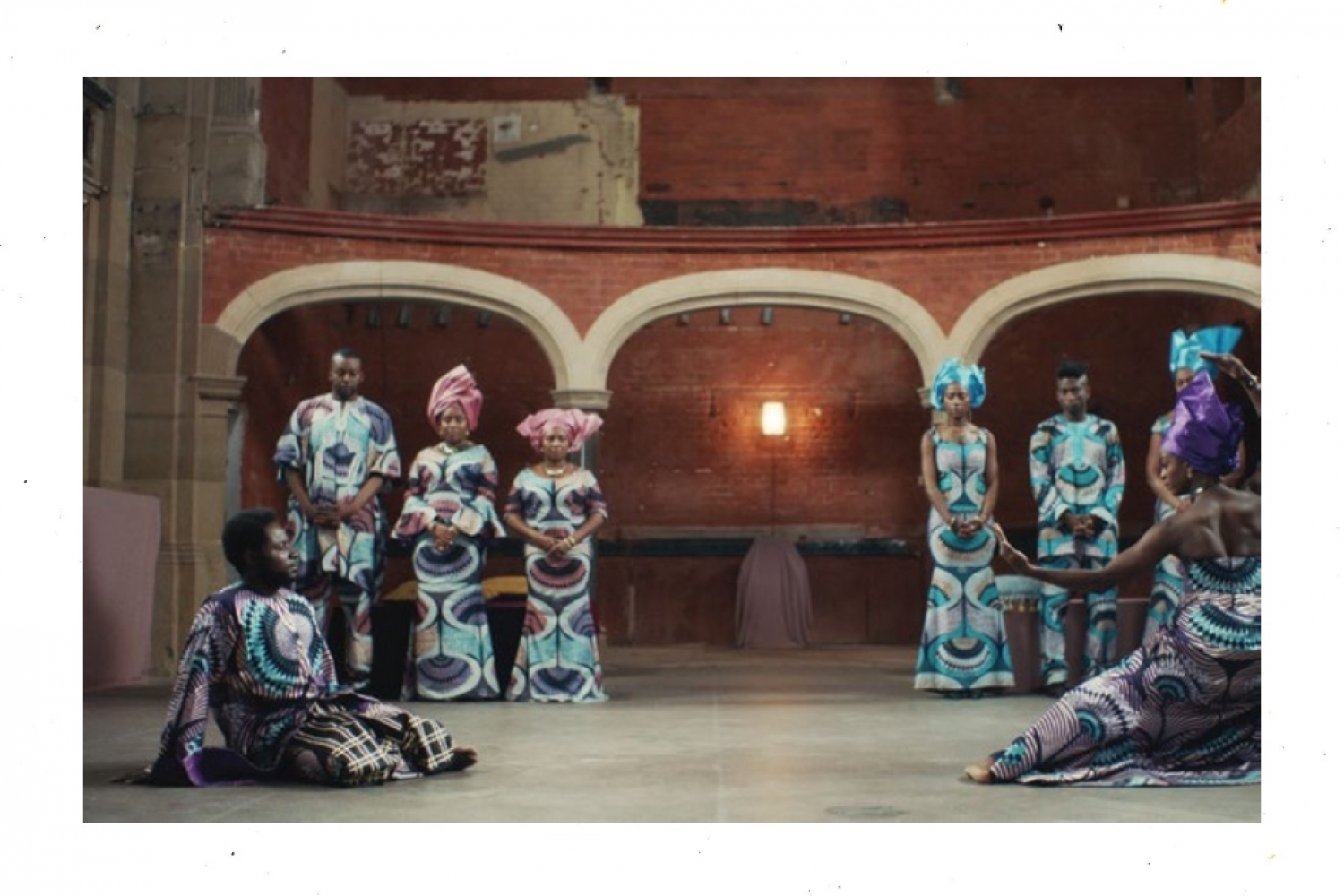

Don’t Look at the Finger (2017) by Hetain Patel. Still pho- tographer Nick Matthews.

Rana Begum, Hetain Patel and Salman Toor are three contemporary artists who are bringing various facets of the South Asian art experience to a global audience. Their art is deeply nuanced and attempts to bring a shift in perspectives. Earlier this year, about 120 dilapidated beach huts on the Lower Saxon Way seafront in Folkestone, England, for instance, were aesthetically restored.Artist RanaBegum was invited by The Folkestone Triennial, a site-specific creative arts festival, that began this July, to transform the town’s sweeping sunlit beachscape into an artistic backdrop.

Begum’s works boast of a restrained colour palette and are rooted in minimalism, symmetry and movement. Whether it’s No. 695 Abraaj, a floating expanse of multihuedtriangular glass plates conceived for Art Dubai in 2017, or her iridescent foil grid collection, where each crumpled surface mimics the contours of mountain ridges— Begum’s oeuvre is magnetic. Her art pieces reveal or conceal, depending on where the viewer is physically situated. The palette of colours she uses transforms under the spell of natural light. For instance, the beach huts’ striking hues are juxtaposed with or tempered by soft tones. “I use a lot of bright and pastel colours. The vibrant, upbeat hues give a certain experience, while the others give a calming, meditative experience,” explains Begum. “For the huts, I was interested in bringing that colour gradient to work with hard edge geometry, where due to the change of light, you see them interact. At the same time, as the viewer gets closer to each of those huts, the experience becomes quite different,” she explains.

Begum designs her (often) large- scale creations by experimenting with myriad materials and textures that give them an ethereal appearance. Take for instance, the spray-painted fishing net that appears to be suspended mid air and resembles a free-flowing drape; or how she has ambitiously used fragile glass panels, steel meshes and even worked with curvaceous forms of marble that deceptively appear weightless when light falls on them. The timber beach huts, however, “were not an easy material to paint on,” confesses Begum. “But I work with various materials, so I’m not someone who is put off by different challenges that the material would bring.”

Begum has remained fascinated by directional signage like road signs that provide a sense of motion. Movement anchors her work—whether it’s in the transitional nature of light that brings her art to life or geometric symbols that signal direction or transition. A few of the huts, therefore, feature a precise triangular motif, which Begum says, “automatically creates movement” and is there to indicate “a change in direction.”

For artist Hetain Patel, who is Begum’s contemporary, movement is inte- gral too, but he employs it differently. From ‘The Jump’, a video set at a glacial pace that depicts Patel—clad in a self-tailored Spider Man suit, launching off a family sofa, to ‘It’s Growing on Me’ a performance piece that closely documents the steady cultivation of his facial hair—Patel has a keen understanding of how movement arrests attention.

His film, ‘Don’t Look at the Finger’, which was acquired by Tate earlier this year, features meticulously choreographed Kung Fu moves. It’s a wedding ceremony of an Afro-Caribbean couple, where vows are expressed in sign language and bodies speak openly through fluid physical gestures. The ceremonial ground soon becomes an arena for the battle of the sexes. “I think it’s just really human to move,” says Patel. “And it’s through the movement of our bodies, through body language, that we understand the world. I find martial arts an extension of the body communicating beyond words, in a very direct way.”

Even the exquisitely stylised cos- tumes worn by the couple shape-shift— the crisp fabric twists, tightens, collapses, reveals and takes flight. It’s the movement of the costumes that is mesmerising. Through art, Patel tackles themes of identity, language and inclusivity. He draws marginalised groups to the centre stage, by giving them Hollywood or pop culture references. “I think on a very basic level I want to encourage the acceptance of difference,” he says. And so, he is inclined to disturb the established ‘normal’ and makes tenacious efforts to nudge the pre-conceived. “What I try to do with a lot of my work is set something up for the viewer that they are culturally familiar with, and then upturn it,” explains Patel.

In the film, for instance, “first you see an African couple in a wedding ceremony and you accept that. Then, you realise they are deaf or that some of their family members are deaf, so there’s a shift in your perspective. Then suddenly, there’s a combat where the couple begins to fight; and then, there are these transforming costumes.” In essence, he wants to disrupt the human tendency of making assumptions.

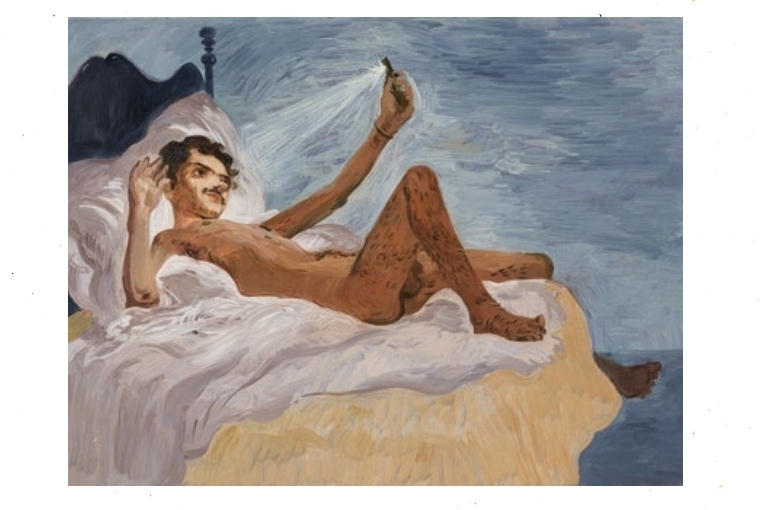

Salman Toor is another artist whose delicate, brooding male figures steer away from conventions. They are queer, brown protagonists that exist in his compelling universe, floating between the imagined and the experienced. Whether it’s a solitary man taking nude selfies, a couple caught in a quiet, tender embrace, or a cluster busy in quotidian social pursuits— Toor attempts to subvert what we’ve been used to seeing in a heteronormative culture, while simultaneously trying to undo the prolonged erasure of the South Asian experience of art in the western sphere.

Bedroom Boy (2019) by Sal- man Toor. © Salman Toor; Cour- tesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

His first solo museum exhibition at Whitney Museum of American Art titled, ‘How Will I Know’ that wrapped up in April, offered a series of paintings that revealed the complexities of race, gender discrimination and alienation felt by South Asian queer men in adopted lands. For instance, one work depicted a brown man being held up by airport authorities, while being asked to present his belongings.

Often drenched in a glowing jade green tint, Toor’s paintings are quasi-autobiographical—essaying the imagined experiences of gay men belonging to the diaspora. These figures populate small rooms and packed nightclubs—yet the space constraints render a gripping sense of intimacy. Viewing each painting feels like an intrusion into their world, where we become voyeurs. While the three artists have disparate practices, each of their works provides an experience, inviting viewers to weave their subjective perspectives with the overarching voice of the artist.

Text Radhika Iyengar

Date 04-01-2022