Last month, Tate Collective invited young artists, aged 16-25, to respond to selected artworks from their collection. What’s unique about this exhibition is that it’s not happening in the Tate Museums or galleries, but on billboards all across the city of London! These inspired works, which range from make-up looks to poetry, are currently around the city in an attempt to make art more accessible, and introduce the general audience to classical works through contemporary interpretations. According to Maria Balshaw, the Director of Tate, and Tobi Kyeremateng, a panellist, ‘The aim has also been to spread a message of hope and creativity during the pandemic, a time of global despair and uncertainty.’

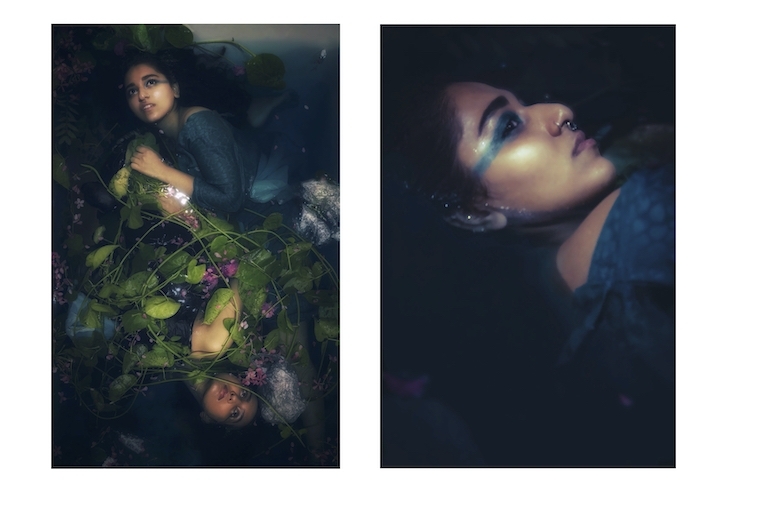

Making India proud in the U.K. are four girls whose project, a response to the iconic oil painting Ophelia by John Everett Millais, got selected from over 800 entries around the world, and is currently on display on the streets of London. Theirs is an all-girls team of four, Astha Patel, Rahi De Roy, Pranshu Thakore and Savitha Ravi, all recent graduates from the Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU Baroda. In 1851, Millias depicted Ophelia, the heroine of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, as a tragic but serene figure. Ophelia’s melancholic grace has captured people’s imagination across time and geographic boundaries. In India, Shakespeare’s plays are still widely taught and revered, perhaps a remainder of our colonised past. ‘Our photograph reimagines Ophelia in the context of our own cultural heritage, and the contemporary issues we see around us,’ says Rahi. They share more about the project and their practice.

When did you learn about this initiative by Tate and decided to give it a shot?

The Tate Collective, an initiative of the Tate group of galleries and museums for young creatives aged 16-25, had announced the open call on their Instagram and a friend of Rahi’s sent it to her. The requirement was to choose one work from the selected collection given on the Tate’s website and make something inspired by it, which would be displayed on billboards around London.

Tell me about your creative process? How did you guys decide what route to take with the artwork?

While conceptualising, we intuitively agreed on the same painting, Ophelia by John Everett Millais. The Romantic aesthetic, and emotionally expressive quality of the artwork immediately drew us in. We have explored depiction of natural elements in our personal practices so the lyrical forest setting was really attractive to us. Rahi was familiar with the character of Ophelia as she has always had an interest in literature, and had written and directed a musical based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet during her school days.

What was the main inspiration behind your idea?

In Hindu mythology as well as indigenous cultures of India, water bodies are often personified as feminine forms. We have stories of river goddesses and maidens born of water. From an ecological point of view, this personification nurtures empathy and a creative relationship with these ‘bodies’, rather than a destructive one. Today, our water bodies are being choked by plastic waste and poisoned by toxic chemical effluents from industries. With our project, we embody the death of Ophelia, as a visual metaphor for a dying river

We were very clear that we wanted to ‘re-contextualise’ the work and not just recreate it. We discussed the dissonance between the serene and lovely visual and its tragic narrative, which is essentially about a woman being driven to madness and ending her own life. In Baroda we have the Vishwamitri river flowing through the city — in fact it is right next to our college, which is so full of plastic pollution and industrial effluents that it resembles a gutter, more than a river. And this is the case for many water bodies in towns and cities across India. In drowning Ophelia in contemporary Baroda, this was an inescapable visual and environmental reality that we incorporated in our imagined retelling. Riverine pollution is not unique to India, yet it presents a strong irony when juxtaposed with our heritage of worshipping water bodies as a form of the divine feminine.

How did you further execute your idea?

The execution of the idea was all about using the resources we had. We met at a friend’s house one afternoon and shot the images in her bathtub. Savitha brought her sister Haritha along to help out. We picked some flowers and creepers along the way, which was easy to find during the monsoon season. We made our own lighting and reflectors on the spot. Due to the pandemic, we shot indoors and made sure to sanitise everything to the best of our abilities. Things went smoothly as we were all clear about the vision and the mood of what we wanted to convey. Rahi and Pranshu had modelled before and Astha and Savitha had some experience with photography, so we all pitched in our skills and experience. We were done by sunset and enjoyed some ice-cream during the golden hour before heading home, editing and sending out the images just a few hours before the deadline.

Text Hansika Lohani Mehtani