They have been apart only two weeks in their entire life. they are identical twins and have been wearing identical clothes since the ‘80s. they have had similar interests since the very beginning. they don’t like to be photographed separately as they are a team, and yes, they prefer being referred to as ‘the singh twins’. The Singh Twins were raised in a very white-dominated area in the UK. Their father was a GP, so pursuing Medicine was a natural choice. Art, on the other hand, was always a fascination, a hobby that came to them easily, but it was never a choice of profession. However, their school teachers believed otherwise, constantly stressing that Art should be their chosen field, not Medicine. At every stage, they were met with resistance and the more they were pushed towards Art, the more adamant they became about not pursu- ing it. But as they say, one cannot fight destiny and neither could they.

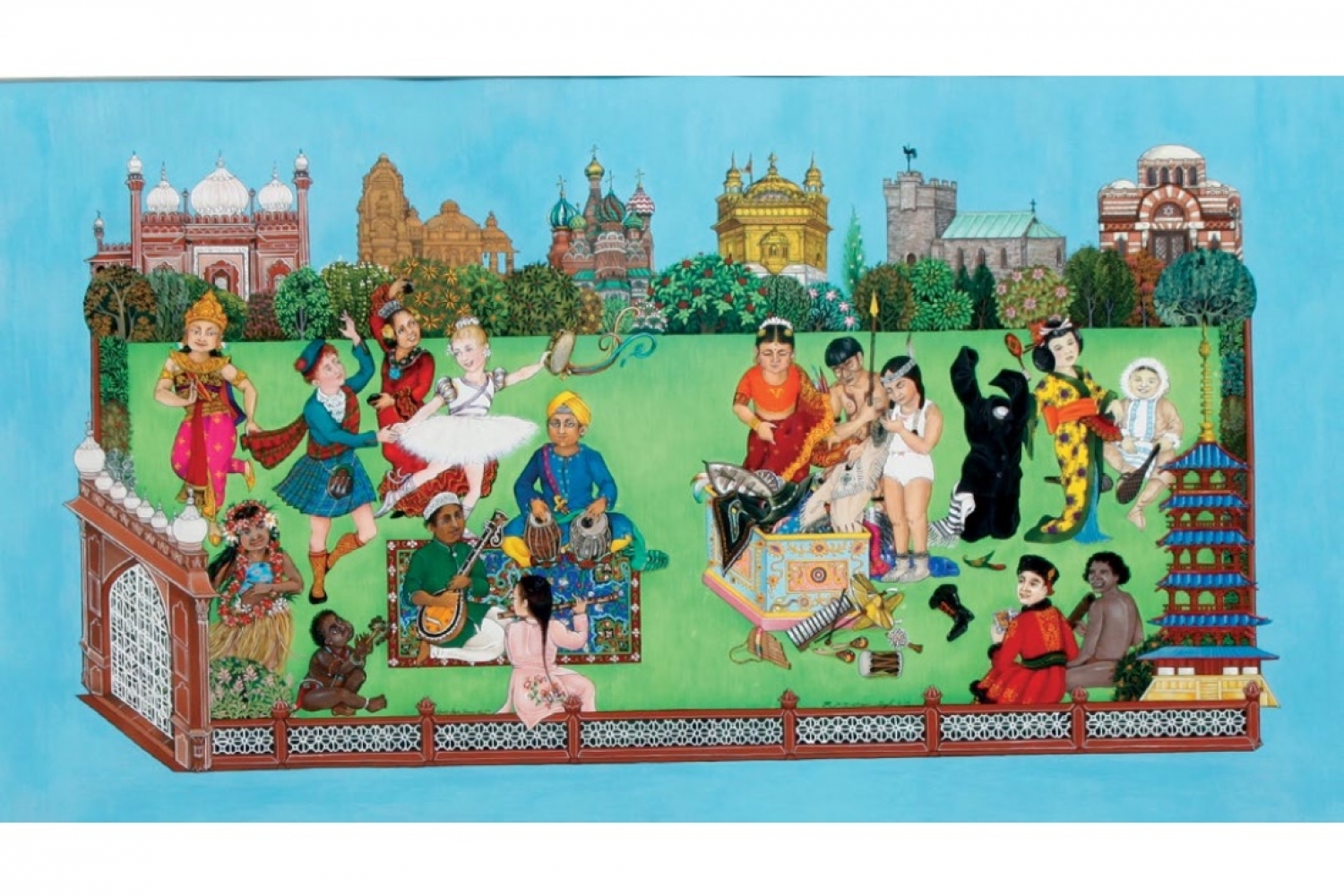

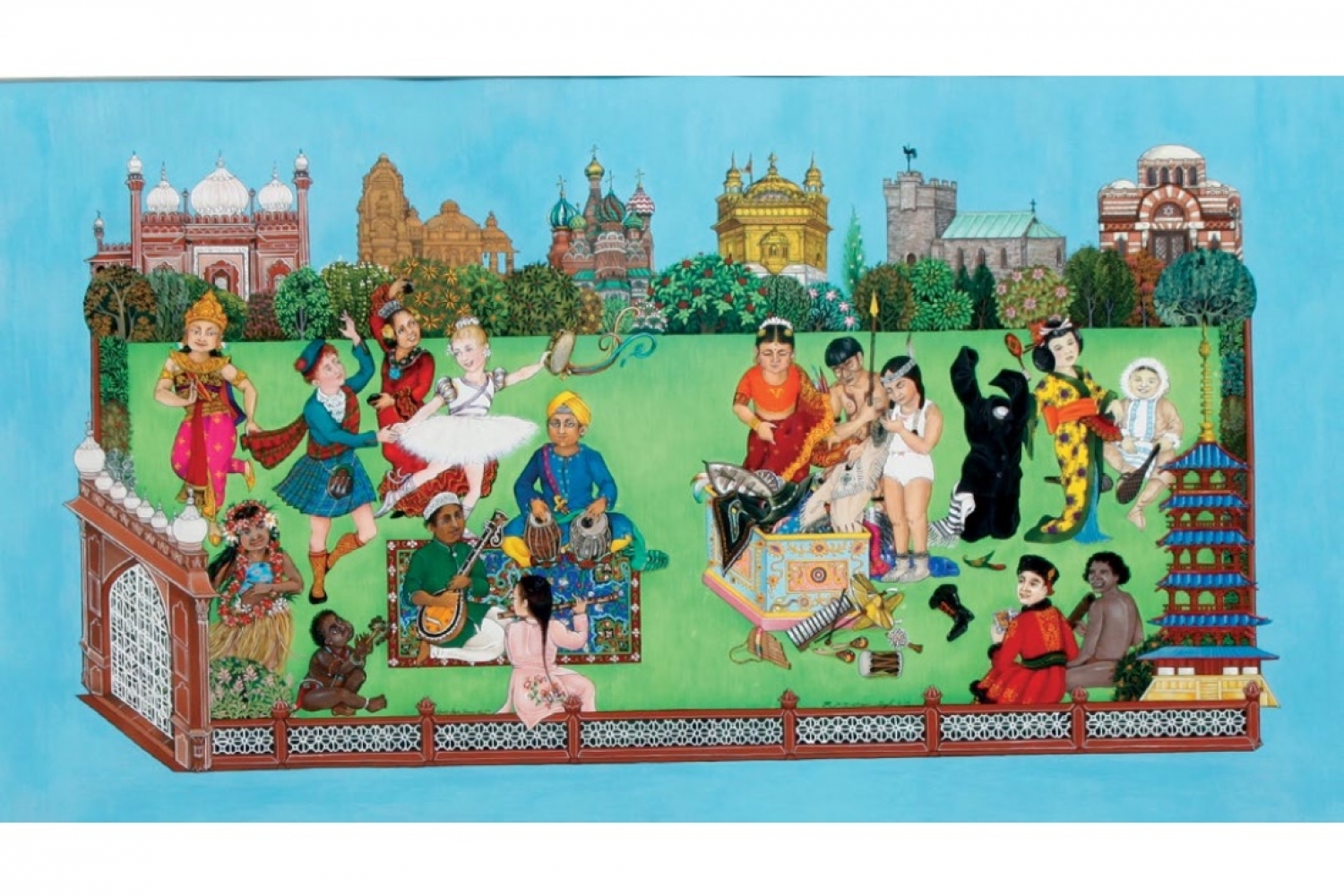

In an intimate, hour-long conversation they walked me through their fascinating lives, and their art that weaves together the past and the present, juxtaposes the East and the West, tradition and modernity in the form of Indian miniatures, thus reviving the intricate art form.

Let’s start from the very beginning. What made you switch from a career in Medicine to a career in Art? When did the romance with the field begin?

Our fascination with Art began the day we were born. We always found ourselves drawing, scribbling and sketching on something or the other. We would sit side-by-side and draw, copying pictures from the fairytale books and write our own stories down to go with it. The only exposure to Art we received outside our home was through our school. We went to a Roman Catholic Convent school and art was always a hobby for both of us. Ironically, our teachers in school were against us studying Medicine, as they felt that we had this great talent for art and thus, wanted us to pursue it. They pushed us to apply to Oxford and Cambridge to pursue an Art degree, but we were adamant to not pursue the field. This was because, to us, it was just something that came easily and was merely a hobby, which they did not understand. So as a compromise we came to an understanding with our teachers, that apart from applying for Medicine, we would apply for Art, but only as a fallback option. When we went for our first university interviews, we were questioned about why we weren’t pursuing Art. That really threw us off, as we deliberately did not put anything forth regarding art in our med-school application and had also asked our teachers not to mention it in their recommendations. When we confronted them, they shrugged and denied having mentioned anything at all about Art.

We did not believe them, so we sneaked into the office where our confidential files were kept, went through our files and there it was in the first paragraph, written by the same teacher who had denied having mentioned anything about art in our recommendations! The paragraph read: ‘these girls are only pursuing Medicine because of parental persuasion and family tradition. But they are really good at art,’ and so on. Apparently they had this stereotypical idea of Asian families, where the children were only allowed to pursue a professional degree like Medicine, Law etc. So we realized that we were not getting any offers from medi-cal schools because of those recommendations. And we were so naive at the time, that we did not have the guts to go and confront our teachers as we were afraid that we would get into trouble for looking at confidential files, so we kept it to ourselves and became even more adamant about not pursuing Art. Because of our teachers’ lack of support, medicine was no longer an option for us and therefore we applied for a BA (Hons.) Degree in Combined Studies. We had to choose three subjects for the course and since we had an interest in world religion, we applied for that. With that, we chose Comparative Religion, Ecclesiastical Literature, History, and believe it or not, 20th Century Western Art History, since it was the only subject left that fitted into the study timetable.

So where did academics fit into your art world and how were The Singh Twins born?

Academics hasn’t left us. We research every piece we do; whether it’s social, historical or symbolical—every piece has a message and does creates issues of debate. We see ourselves don’t always reflect our point-of-view, as we are social commentators, documenters or observers. Whatever’s happening or is relevant to society—be it popular culture, politics or the world of sports—interests us. Although it’s not always our point-of-view that we express, we leave it for the viewer to interpret and sometimes we give both sides of the debate. After completing our degree we did a period research for a PhD in Sikh Art and Heritage, with the intention of pursuing a career in academia. But mid way through, our supervising Professor sent to work elsewhere. As we waited for the University to find a replacement, we decided to promote our artwork and we were soon ready with our first UK exhibition tour. Things just snowballed from there. And then, ‘The Singh Twins’ were born.

How does your equation work when you are in front of a blank canvas?

Before the blank canvas comes along, our every painting starts with research and that’s done together through the Internet, libraries, archives etc. Then we correlate all the information by writing notes and go through the checklist of all elements that we want to include in the painting. After that, one of us gets on with the admin, PR or another commission work whilst the other starts the process of creating the initial ‘sketch’ that starts off as a computer generated composition. So a lot of imagery is taken from the Internet or scanned from books, photos, or hand drawn and is imported into the computer where it can be easily resized and reworked. Then we both decide the final composition, which is copied by one of us to paper, creating a very detailed line drawing. And once that’s approved, the painting process begins. This is done collectively—either in rotation or simultaneously, whichever works best.

You have revived the miniature art form. What drew you towards miniatures?

As children we remember a few miniatures hanging in our home which we hadn’t paid much attention to earlier. But they began fascinating us back in 1980 when, as teenagers we made our first trip to India, which was done across land. Our father built this motor-home with his brother and we drove from England to India through Europe, the Middle East and Pakistan. It took us a month and it was a real adventure and to add to that, it was in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war! Our father was going back to India after 30 years, so he was really excited. It was at that time that we discovered the miniatures in New Delhi at the National Museum. We were just overwhelmed by this tradition, and once up close, we could see the texture, the detailing, the emphasis on each line or stroke. We just couldn’t believe these were done by hand. During this time, we also went to the contemporary art galleries and felt that no one was taking the miniature art form seriously.

Even the museums treated them like something of no value and we felt it was a real shame. It was at that point that we made it a mission to bring the miniature back to the modern audience and make it relevant. We headed back to England and took back a book on Imperial Mughal miniature paintings that became our reference. We began by copying some of the classic miniatures, but couldn’t really delve into it too much as in school there was more emphasis on Modern Art. But when the time came to develop our own style during our university days, we immediately wanted to go back to that miniature tradition so we referenced some more historical examples to teach ourselves the technique, resulting in our own interpretation of the miniature style. We had our own hurdles pursuing the miniature style as it was considered ‘old, backward and outdated’ by our tutors who dismissed the tradition as having ‘no place in contemporary art’ and pressured us to follow western role models in art history. It’s not been easy to gain acceptance for our style of art within a contemporary art world dominated by a Eurocentric outlook. But a good thing that has come from the negative attitudes and barriers we have experienced along the way is that it’s made us fighters. It’s given us a goal and a common cause as artists to act as a united front against the institutionalized cultural prejudice that we have faced from the art world and mainstream British society. Having said that we still have so much more to explore within that tradition.

Photography: Tanuj Ahuja

What do you try and communicate through the miniatures?

What we found was that traditional miniaturists were documenters of their time as they painted, for example, the historical battles. They gave a day-to- day, detailing the courtly life and reflected the religious beliefs of the time. So there was no reason why we couldn’t apply that language to the modern day context. We started developing our work keeping the Indian aesthetic in mind, while looking at contemporary issues. The early work we did was more or less focused around our own experiences as Asians growing up in the UK. So there was an emphasis on the extended family, the tradition of arranged marriage and so on. We were trying to show a positive side of those traditional Asian values, which were generally negatively stereotyped in the minds of the Western people, largely because of media misrepresentation. So that was the genesis and as time passed our ideas evolved, we travelled and got more exposure and other influences crept into our work as well.

How have you evolved as artists?

Our first national UK tour was in 1999. Since then, we have exhibited across the globe and evolved in both medium and style. We have explored animation, film and digital art. Our first film (Nineteen Eighty-Four and the Via Dolorosa Project) was about our painting, Nineteen Eighty-Four. The film came about because we were asked to take part in a multi-faith project back in the UK whereby a Christian priest asked artists from different faiths to respond to the Catholic tradition of the Via Dolorosa or Stations of the Cross. We wanted to link that Catholic expression of Christ’ suffering to the Sikh experience of 1984 when thousands of innocent pilgrims including women and children were killed and injured during the Indian Government’s military assault on the Golden Temple.

So we drew parallels between Christ’s treatment as an innocent individual who was humiliated with the treatment of Sikhs in 1984. That became a 25-minute documentary. The painting itself was created as our response to the media blackout that occurred after the attack on the Golden Temple. In terms of animation, our first inroad into that medium was in 2008 when we were commissioned to create a new work celebrating our home city of Liverpool’s 800th anniversary, which we later decided to make into an animated film. That was also our first collaboration with artists other than ourselves as we worked with a team of animators and a musician on the project. The narrative for the animation took the form of a poem. Since then poetry or creative writing has also become an important development in our work. Now we have the bug for animation, and are thinking of doing a series of animations on the histories of various cities like Delhi for example.

What’s in the pipeline?

We have just completed a commission for the National Museum of Scotland. It’s based on the life of Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last Maharaja of Punjab and his connection with a British character called, Sir Logan who became Duleep Singh’s guardian when his Sikh Kingdom was annexed to the British Empire. He was brought to the UK when he was nine, to be brought up as a Christian, English gentleman. It’s a very sad story actually, where there is a loss of heritage and identity. The painting is a portrait of him but it’s very symbolic as well. It’s done in miniature style, but it’s quite large in its dimensions and conveys a lot about the history of Anglo Sikh relations and the politics of the Empire. It’s due to be unveiled as part of a touring exhibition and educational program next year. We are also developing a highend accessories line, translating our work on to scarves, bags and jewellery. We are also looking at developing a line of collector’s edition prints. In addition, we have just finished designing a calendar and commemorative coin celebrating the Sikh contribution in the World Wars— both of which are to be launched this November at the Sikh Arts and Film Festival, California.

This interview was first published in our Film Issue of 2013 and is a part of our extensive archive that we are revisiting.

Date 28-08-2021

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra