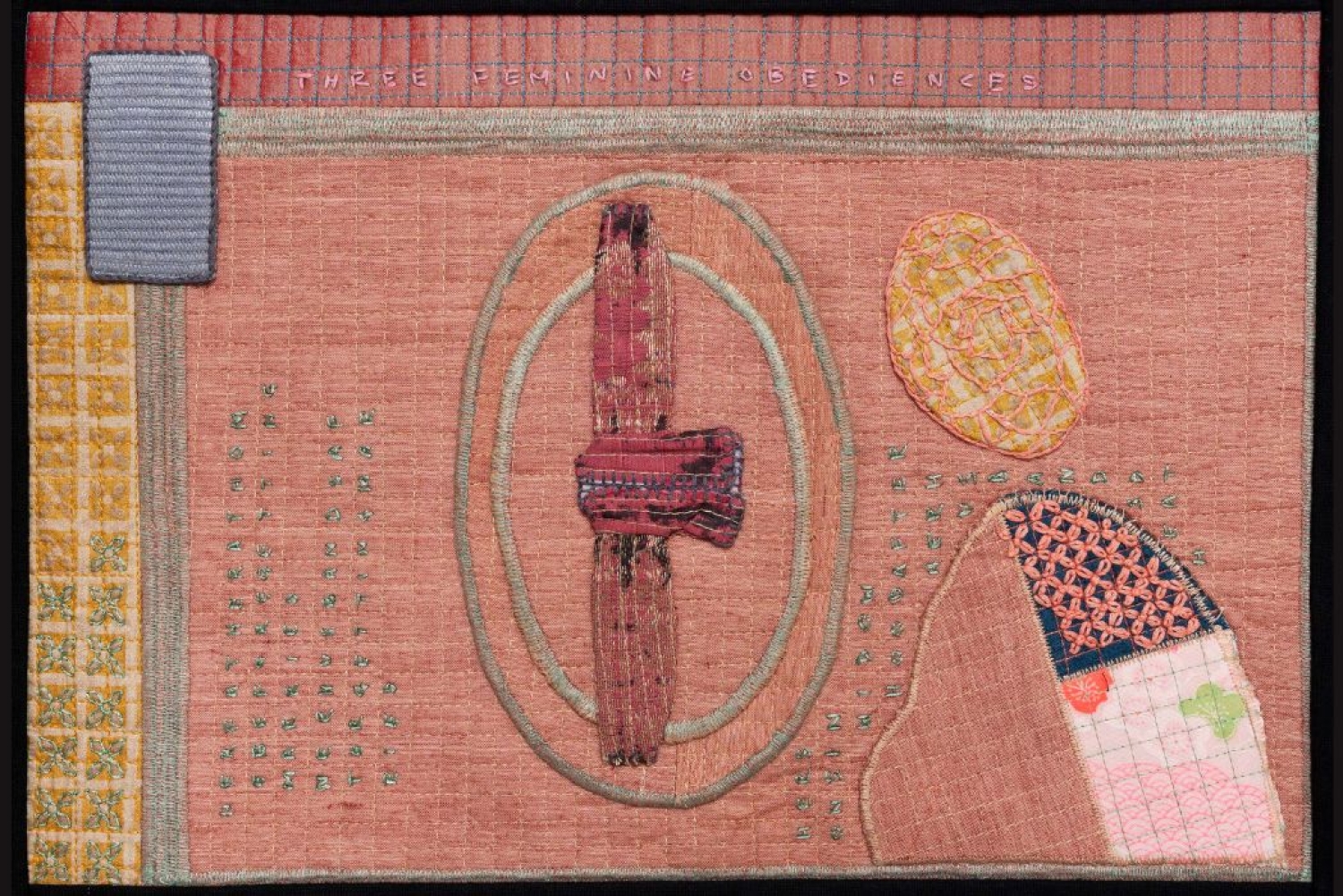

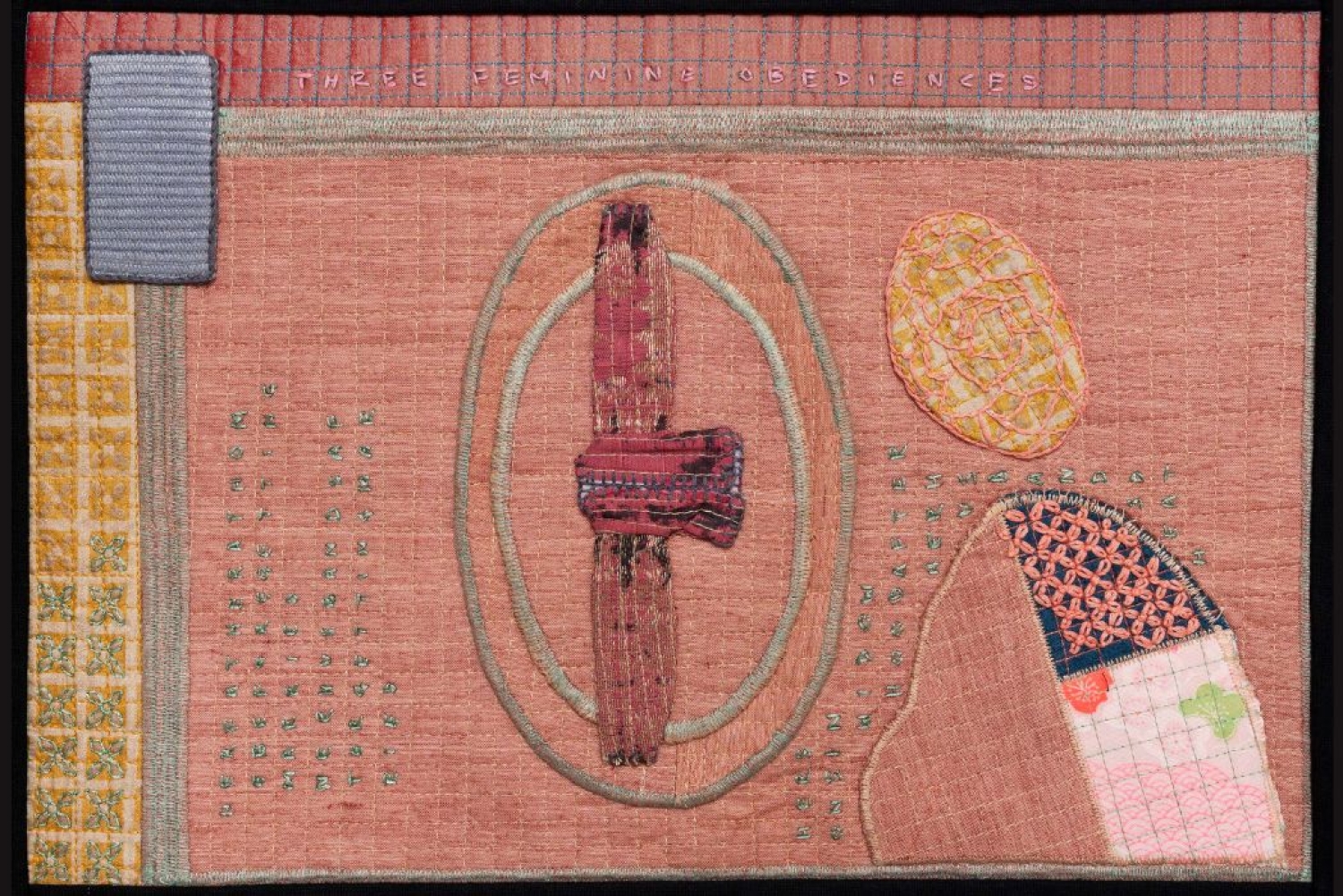

Artist Kallol Datta’s latest solo exhibition at Experimenter, Colaba, offers a compelling exploration of how textiles can serve as a powerful medium for social critique. Building on their deep dive into the history of land laws and their lasting effects, Datta explores these themes through textiles. The show features provocative works created from materials gathered over years of research. Using textiles as a lens, Datta examines issues like gender politics, social hierarchies, class divides, censorship, and broader socio-political debates. This exhibition is a continuation of their ongoing study into traditional clothing practices from Japan and Korea over the centuries. The pieces powerfully remind us how clothing norms continue to shape conversations around popular culture today.

What inspired you to explore historical laws and their lasting impact on Contemporary societies in your artwork?

In 2022 I came across Lessons for Women, by Ban Zhao; China’s first known female historian. The book was also known as Admonitions for Women, Women’s Precepts, or Warnings for Women. The circulation of Lessons for Women reached its peak during the late 16th century, but its influence is still felt across East Asia and Southeast Asia today.

“Exhibit tranquillity, unhurried composure, chastity, and quietude. Safeguard the integrity of regulations. Keep things in an orderly manner. Guard one’s action with a sense of shame. In movement and rest, it is always done in proper measure. This is what is meant by woman’s virtue. Choose words [carefully] when speaking. Never utter slanderous words. Speak only when the time is right; then, others will not dislike one’s utterances. This is what is meant by woman’s speech. Wash clothes that are dusty and soiled, and keep one’s clothing and accessories always fresh and clean. Bathe regularly, and keep one’s body free from filth and disgrace. This is what is meant by a woman’s bearing. Concentrate on one’s weaving and spinning. Love no silly play nor laughter. Prepare wine and food neatly and orderly to offer to the guests. This is what is meant by woman’s work.”

This excerpt from Lessons for Women seemed absolutely ridiculous and familiar at the same time. Familiar because I wouldn’t be surprised to see this text attributed to a politician or religious figure from any part of the globe in the 21st century.

And thus began my research into sumptuary laws, religious and imperial edicts, and statutes of the past, which formed the existing social codes of today.

How do sumptuary laws, religious edicts, and imperial proclamations shape modern life in Korea and Japan? Why were these countries chosen?

My research spanning over a decade into clothing practices native to the South West Asia - North Africa (SWANA) region, the Indian Subcontinent, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan has a particular focus on the period between 1945-1989. For some projects, the exploration may branch off towards newer, diverse areas that are still related to my core research. For Volume IV: Truths, Half-Truths, Half-Lies, Lies, posters, clothing, architectural drawings, and cartographic surveys foreground how East Asian Confucian principles impacted daily lives - both public and personal and how they informed societal norms even in Vietnam and the Philippines.

Historical episodes related to clothing practices and social codes helped me map out how abject class structures and notions of morality of that time are now visible in the very laws and societies of the regions of my interest. I find it imperative to expand upon these rules and subvert them by reimagining these social codes that have existed for centuries and directing them towards the authoritative powers that have benefited from them.

Can you walk us through your creative process—how did you translate historical research into visual art?

The research I conduct begins with working out what specific interventions I hope to stage with my practice, and that leads to collating data through on-site visits, accessing texts at libraries and material archives at museums and cultural institutions, organising clothing drives, and interviewing donors of the drives as well as academics.

Once I analyse the information collected, I experience a phase of exhaustion and take a break. With every project or body of work, I spend around two to four weeks charting my build plans, which consist of lists, renderings, and detailed notes, followed by the phase of producing the new works.

For example, Volume IV unfolds through four chapters and for the chapter Half-Truths Our Clothes Told Us textile works rooted in research on advertisement posters and flyers in the Meiji, Taisho and Showa periods in Japan are produced in the exact dimensions of the historical material, but at a closer look, codes inscribed onto the textile surfaces emerge.

What specific materials or artistic techniques did you use to reflect themes of censorship, morality, and class structures?

Volume IV: Truths, Half-Truths, Half-Lies, Lies negotiates patterns of censorship, alienation, and mobility through materials collected during my research and clothing drives. The aforementioned build plan for each work comes into effect with an intricate mapping of grids via multiple quilting methods, embroidered texts, and mnemonics that mark acts of resistance, dissent, and defiance.

What impression did the research and the art-making process leave on you, and what emotions or reflections do you hope audiences will take away from this exhibition?

I think it’ll take a while for me to acknowledge and process the research and making of Volume IV: Truths, Half-Truths, Half-Lies, Lies. I do hope visitors to the solo at Experimenter, Colaba, are able to contextualise the works beyond the gallery environment, meaningfully engage with them, feel emboldened to have conversations and perhaps continue this dialogue even after the exhibition ends.

Words Hansika Lohani

14.07.2025

Photo credit Rusha Bose