Shubham Negi hasn’t called himself a filmmaker for very long. Although he has been interested in art from early childhood, the process of becoming a filmmaker was a gradual one. It started with performing skits in school, to being a part of the drama society of his college, to writing jingles for street plays, writing poetry for Hindi magazines, stories for literature, and then, finally, on-screen stories. This relationship with storytelling formed over years, but the connection with telling them through the medium of cinema is new. But it is a strong one. ‘Films, because of their very nature of arresting multiple senses, offer a medium that is vast and unparalleled, to make people live in the world a writer creates. But since poetry is something that feels otherworldly to me, something that makes one feel so much with so little, I try to bring poetic moments into films as well.’ he says, on the art of film-making. Although his relationship with films is growing, in the end, he hopes that his films are remembered for the smallest (and hence, the largest) moments that stayed with the viewer.

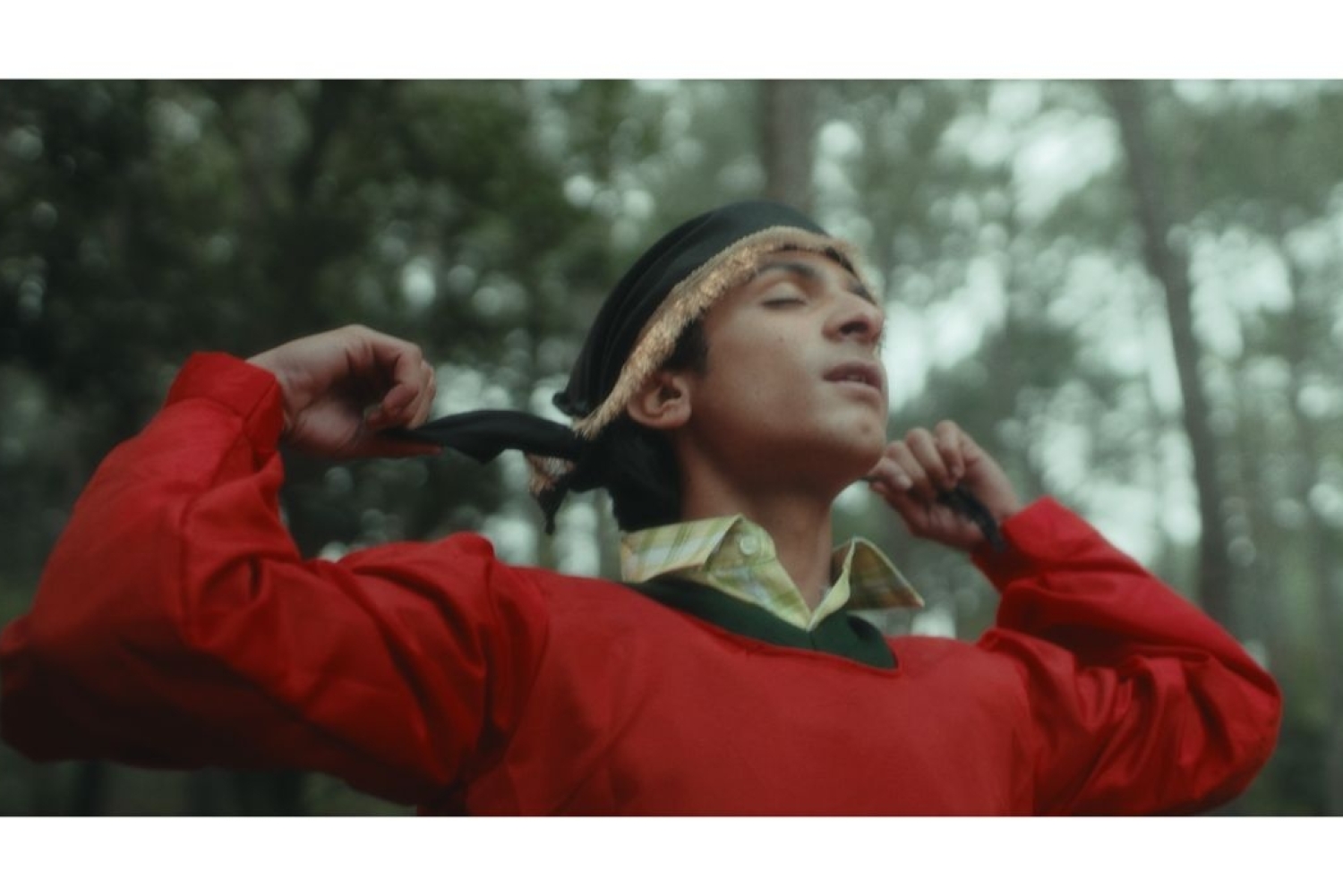

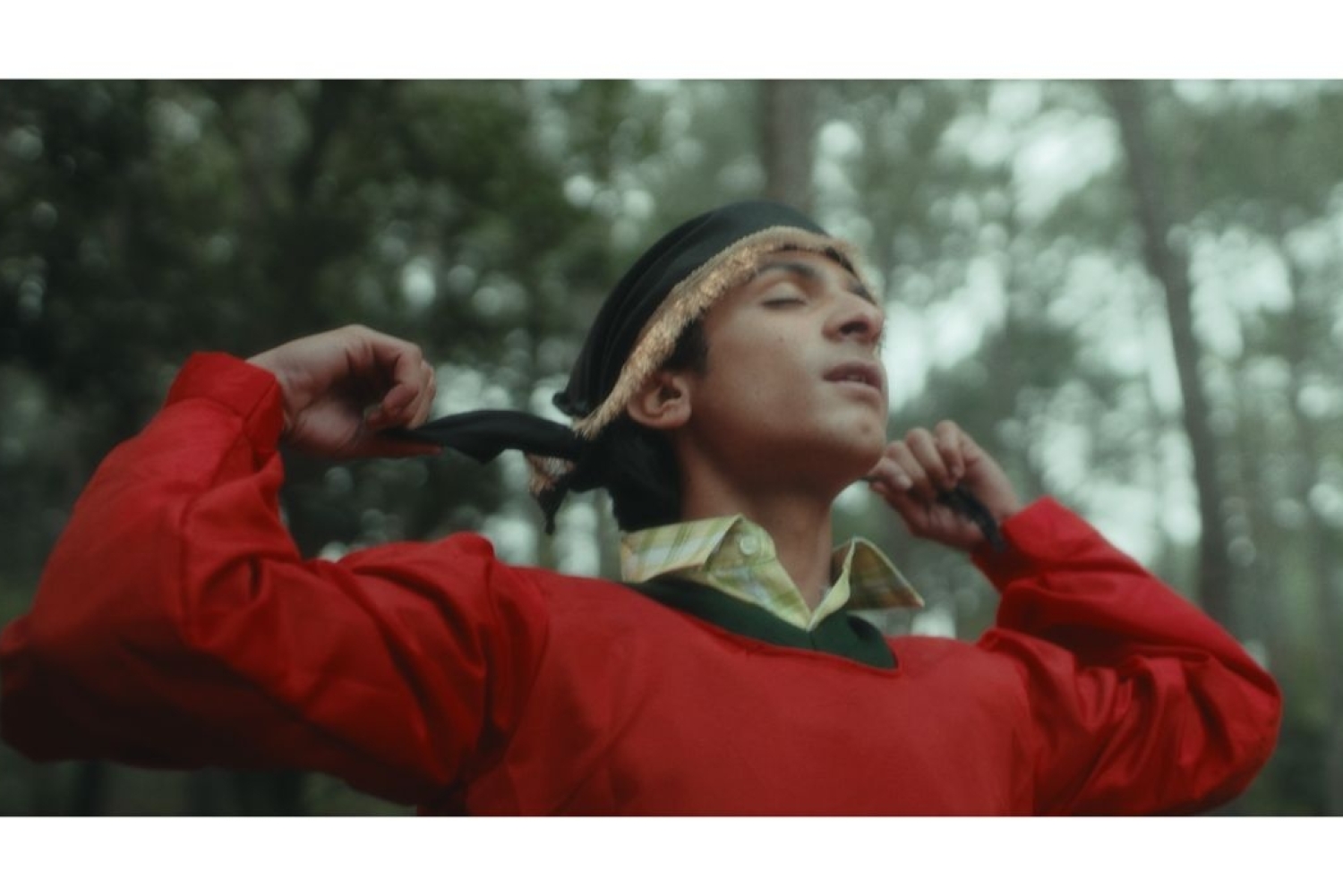

Premiering at the Academy Award-qualifying Rhode Island International Film Festival and developed through Netflix and Film Companion’s TakeTen grant, Hills Don’t Dance Alone is set at a school in the Himalayas, where fifteen-year-old Sachin is bullied for cross-dressing in a folk dance performance. Anju, the middle-aged vice principal of the school, steps in, but it unravels more than she anticipated. As both quietly navigate their secret struggles, their lives begin to intertwine, forming a bond that neither can name but both of them need. We spoke to him about his process, inspiration, and much more.

Tell us about the setting of the film. Why did you think the hills were the landscape for this story to take place?

The film is set in my village in Himachal. Giving a fancy answer would be a lie as it’s simply based there because I come from the place, and it came quite naturally to me. Also because the film is a personal story in many ways.

But, having said that, the choice to put this story in a rural setting was a conscious choice. We have seen the Indian queer discourse evolve over the past few years, but most of it has been through an urban, upper-class lens. With this film, I hoped to bring the lens to a small village in the Himalayas, and say that, other than the scenic drone shots of the hills, we deserve a knock on our doors as well. We are come-of-age as well, we struggle with our identities, our dreams. The past two-three years have seen quite a few amazing stories coming from the mountains, and I am lucky to add one to the library.

What was the writing process like?

Actually, this short film is a part of a web show that I am developing. Writing has been quite eventful. The first thing I worked on, with my associate writer Shubham Dadhich, was the story and a bible for the entire series. Then, I developed the pilot episode for the show. This short film is a part of that pilot episode we made for the web show. Writing the pilot was interesting in its own way, but cutting it down to a short film was even more so.

The film’s writing draws from whatever I see around in my village. The scenes are set in daily rituals like milking the cows, or cutting grass for them, or fetching drinking water from the local bawdi, etc. The way these people talk are my lived experiences. They don’t say big quote-worthy sentences (have nothing against that), but they speak in the language of local routines. But, the writing didn’t stop at the desk, as it never does.

My team, whom I was fortunate to work with, have shaped the scenes and the story with their input. In particular, Udit Raj Somani, my producer, helped me with finalising the screenplay, fixing gaps, and making it more cohesive than it was on paper. The actors brought their own experiences and language to the characters, breathing life into the scenes. The editor, Amit Kulkarni helped me keep the narrative focussed, while Udit later helped carve the longer pilot into a short length film. So, the writing which we see on the screen is a culmination of this collaboration amongst multiple people.

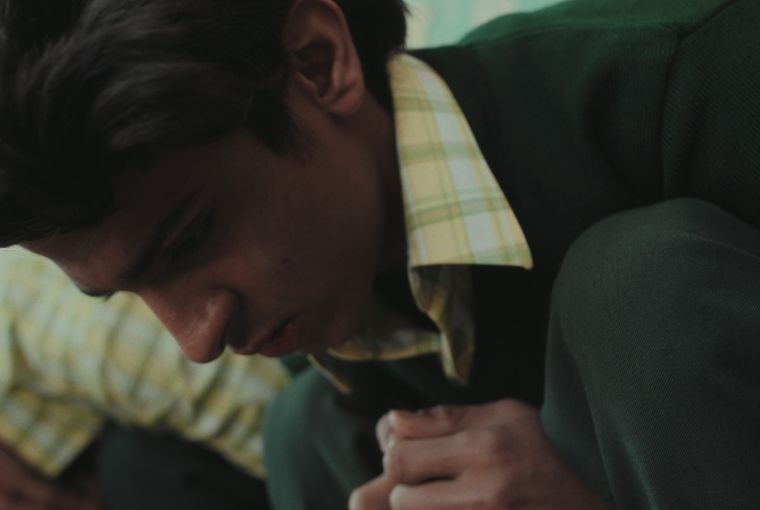

I remember noticing much much later in the post production how the character of Sachin rarely speaks three-four sentences in the entire film. This was a surprise, as I hadn’t thought of it while writing. It never felt like that in the film as well, because of the nuance and unspoken drama Tanishq, the actor, has brought to that character. Similarly, in another scene the two actors, Sangeeta Agarwal Ma’am and Palvi Jaswal, had to speak only three-four lines in the entire scene. But, because of the way we treated the scene, it became the longest scene of more than two minutes. So, I’d say those silences might be what I wrote on paper, but what filled those silences were the actors, who brought something which couldn’t have been written or directed.

Queerness in this film is subtle through it all, like an unspoken, lingering presence. Why did you choose to represent it this way?

When we talk of queerness in rural spaces, we don’t speak of it in words. The queerness here doesn’t have vocabulary to verbalise itself. The people, hence, are more about emotions than identity. The film, in a sense then, is also about finding the words to express it to others, even if only one person. Not once in the film does anyone use the words queer, or trans, or gay, or lesbian. For them, their queerness becomes an unspoken, lingering presence then. This is also one big difference between the urban and rural representation of queerness. With urban stories, a character can find a word for their identity in a scene and I wouldn’t question that. But, for a rural fifteen-year-old kid, for that to happen will require a feature length film. That is, if we are interested in arriving at a label, which I am increasingly starting to get away from.

I was also curious about the setting of a school and building a world within that—what was this inspired by?

I have always felt that schools function as a microcosm of the society around them. Rural schools more so. Hence, they become a strong yet contained representation of what we wish to say through our stories. The school in this story came from the character of the school kid though. His story is personal and the rule in this school, of girls and boys not being allowed to participate together in cultural events, was a rule in my boarding school as well. And hence, for the school skits, I used to crossdress for female parts. Over time, it started to feel like a thing I looked forward to. So, the character of Sachin came from there, and hence his story started with a scene of him being cross-dressed in school. The rest of the story, though, is what I wished would have happened in my teenage years.

The school where we shot is, interestingly, the school of my village, where I studied for a bit, and where my uncle and aunt have taught for years. My brother has completed his higher studies from the same school. So, choosing that particular school as a location was not just a visual choice, but also an emotional choice.

Were there any challenges you faced along the way?

A lot! As is true to every film ever made, especially the indie ones. As we just talked about the school, it reminded me that one huge challenge was finding a school to shoot. We wanted this specific school but since it was a government one, and the shooting month was March, it was extremely difficult to get permission because annual exams were going on. My family and local people were of extreme help in getting us the permission, and Udit was a saviour who planned the shoot in a way that we didn’t disturb the on-going exams. I remember it was Friday, and there was an exam going on in the first half. We had permission to shoot after lunch. The crew of thirty-forty people stood outside the school boundary with equipment ready, and as soon as the exam ended, everyone rushed into their respective corners and started the shoot on time.

There were other challenges as well. The biggest one being that we were shooting a queer story in a village. Since a chunk of the crew consisted of the village folks, we were always in a tussle whether to tell them the entirety of the story or not. And that tussle still hasn't ended as we move forward with other films in similar settings. The house we were shooting in belonged to really lovely people, but we hadn’t told them the entirety of the story for obvious reasons. And that became an issue at times, when we were shooting slightly intimate scenes in their premises. This question bothered us all the time — whether to reveal and bear the consequences or make the film anyway, because, what other option did we have?

But then, the people were surprisingly supportive as well at times. For example, on our first day of the outdoor shoot, I knew my family and relatives were going to come and watch the shoot. We wondered what they would say when they saw a boy dancing in a ghaghra. But, to our surprise and amazement, they were in tears as were we. That scene had a seven minute take and it made everyone cry. From the actor, to the crew, to the relatives who were there to watch what film shooting looks like. These pockets of hope and empathy are what we make cinema for.

What do you hope for people to take away from the film?

I think the idea of empathy is something I wish people understood more. Not just to people who are like us, but to people we don’t fully understand. One of my favorite films of recent times is Everything Everywhere All At Once and there is a dialogue — ‘Please be kind, especially when we don’t know what’s going on.’ I think that is something we need to imbibe into ourselves as people. That is what I wish people took away from the film.

What are you working on next?

I am shooting a short film called Makeup Room, which we are planning to shoot this November. It was developed through my fellowship with Queerframes Screenwriting Lab and won the Kashish QDrishti grant this year.

Other than that I am developing two feature films at the moment. One is a family drama set in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, called Soma Helang. It is a story by this film's (and in general my work’s) DoP, Sourav Yadav, and we will be co-directing it. Sourav, who is an amazing artist himself, brought this story to me when we worked on this short film. The film is being produced by Neeraj Churi (of Sundance Winner Sabar Bonda) and we are excited to make this a reality.

The second feature I am working on is a psychological horror called Things We Leave Behind. I am developing the screenplay at the moment.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 22-09-2025