Raised in Kolkata, Subarna Dash found her voice in art long before film became her language. Navigating solitude and social anxiety, she drew inspiration from a vast range of cinema, her openness shaping a distinctively personal, emotive style.

Her latest short, The Girl Who Lived in the Loo, is both intimate and inventive—an animated exploration of identity and anxiety that premiered at the Berlin Film Festival and continues to resonate with global audiences. Prior to this, Subarna’s This is TMI and Amayi (Mother) traveled world over, each delving into hidden truths about women’s bodies and generational trauma. Having joined Berlinale Talents, Subarna is now channeling her trademark blend of humor, intensity, and vulnerability into an anticipated feature debut, crafting a rich, mixed-media family drama rooted in her own coming-of-age.

What was the starting point for The Girl Who Lived in the Loo?

The film came about during the COVID lockdown, when we were all forced to spend extended periods either alone or with our families, mostly against our will. I found myself thinking a lot about isolation, environment, people we surround ourselves with. And also about spaces. Both personal and public, and what they mean to us.

Growing up, and even today, my space is incredibly precious to me.

I’ve had social anxiety since I was a kid (and, fun fact: I still do). So The Girl Who Lived in the Loo was pretty much born out of that experience. It was less about making a film and more about trying to therapize myself, holding a magnifying glass up to my younger self and wondering: did anything I felt make sense, or was I just 'weird'?

I wanted to portray anxiety the way I experience it, not in some general, universal sense, but how it precisely felt inside my head. Fragmenting, disorienting. So, while the story is rooted in my own experiences, a lot of it is fictionalised. Still, I tried to stay emotionally true to the core of it. The narration of the film was written first, then the rest came about naturally.

Making the film has been incredibly rewarding. It always feels like I’m putting a literal piece of myself out there for the world to see. And while that’s scary, it’s also kind of wonderful.

Did you see the audience connect to it?

What’s been most rewarding, though, is the audience response. People have come up to me after screenings to say they’ve gone through something similar, or are still going through it, and that the film made them feel seen. Those conversations at festivals have been the most special part of this journey. Through this film, I feel like I’m finally able to share a kind of warmth, understanding, and quiet acceptance with others through my art.

Since it was completely animated, what was your process like and how long did it take for you to make the film?

I write and draw simultaneously. I tend to visualize the film early in the process, but that vision evolves as the script develops. I often sketch while writing. It’s a very fluid, back-and-forth process. Drawing helps me think through the story, figure out its rhythm, and get a sense of how it moves visually. A lot of my inspiration comes from real life. I’m always observing people, sketching scenes. The main character’s design was born from one of those spontaneous sketches in my notebook.

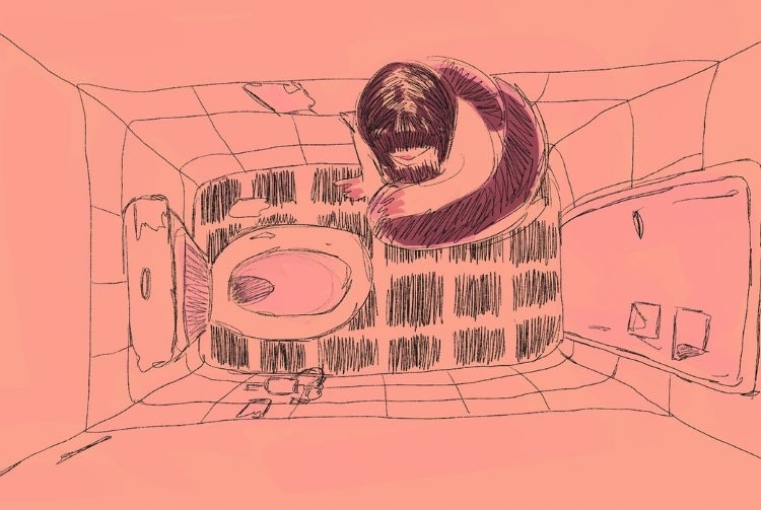

The initial visual concept for the film looked very different from the final version. I started with a watercolor-on-handmade-paper style, cleaner lines, soft textures, and a more soothing aesthetic. But as the story evolved, I realized that 'soothing' wasn’t the right visual language for what the film was trying to express. So, I shifted to a more raw and unsettling style. The lines became sketchier, more restless, almost agitated. I brought in intense pops of colour, neon pinks and oranges, to evoke anxiety and overstimulation. In contrast, the bathroom scenes were rendered in muted tones like beige and grey. These colours represented calm and stability, but also a kind of numbness or boredom. This contrast helped me create a visual tension between the protagonist’s inner world and the outside one, not just in terms of space, but also emotional temperature.

The film is 12 minutes long and entirely hand-drawn, so naturally, it took quite a while. I wrote it during the COVID lockdown and finally began animating it in 2022. Overall, it took about two years from start to finish. I was also working on a short documentary at the same time, which probably stretched the timeline a bit further.

What sort of themes do you gravitate towards?

A mix of things. I find myself drawn to themes around the body, identity, isolation, and the fleeting, often confusing nature of emotions, all framed within the experience of growing up in a Bengali middle-class household. I also try to weave in a certain wit and humour, because that’s a huge part of who I am, and honestly, it was my primary coping mechanism growing up. I want my films to feel like extensions of myself: quite awkward, slightly chaotic, and sometimes funny. Apart from my very first short, most of my work, past and present, has been quite personal. At this point, filmmaking feels like therapy. I don’t think I’ll stop until I’ve dumped every thought and feeling I’ve ever had onto the screen, and made everyone else deal with them too.

And if you can talk briefly about your two films before this?

My last two films were called This is TMI and Amayi (Mother). This is TMI is a mixed-media animated short documentary in which a group of women talk candidly about their breasts. It was a wholesome experience to make because the women featured are some of my closest friends.

In a way, the film ended up documenting the intimacy, trust, and safe space we’ve built in our friendship. The film had a wonderful festival run, premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival, followed by SXSW and others. The audience response was beautiful as well. I also love that some people have asked, 'But what’s the point of the film, it’s just women talking about their breasts?', and honestly, that is the point. That it’s just women talking about their breasts.

The film I made before that, Amayi, was my first short. It’s a hand-drawn 2D animated film based on the topic of female genital mutilation in a tribe in Gambia. The story follows a village cutter who refuses to cut her own daughter. It was adapted from a chapter of the powerful book, The War on Women, by Sue Lloyd-Roberts, which I read some years back. It left a deep impact on me. Filled me with anger, but also a deep admiration for the strength and resilience it portrayed. At the time, we were assigned our first short film at film school, and this story just felt like the right one to tell. Being my first short, I knew very little about festivals, but to my surprise, it went on to have a long festival run, premiering at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival, PÖFF Shorts, and several others.

Since you are a part of the Berlinale Talents, can you talk about your feature film that you are working on?

Being a part of the Berlinale Talents has been incredibly inspiring and rewarding. Right now, I’m working on my first feature film, which is pretty much drawn from my own life. It’s somewhat of a family drama centered around the last couple of years of my spiraling through film school.

The film’s a mixed-media animation because after making my documentary, I fell in love with how fluid and playful mixed media can be. This film again has a bit of a humorous tone to it while tackling some serious themes.

I’m currently writing the script at a writer’s residency in Switzerland, while also working on the visual style, drawing, experimenting, and just writing down any little random thoughts or ideas that pop into my head. Sometimes I sketch those out too. I’m still doing my usual thing of sitting quietly, observing, sketching, and eavesdropping on conversations, though understanding German hasn’t been easy! Honestly, a lot of my time here is spent just soaking in art in all its forms. Museums, street art, films, books, music, and the best kind of art, which is everyday life. I take long walks, watch the river, the birds, and the hundred kinds of bread they sell at bakeries. Sometimes I do absolutely nothing but stare at the ceiling. It’s all part of the process.

Words Hansika Lohani

25.07.2025