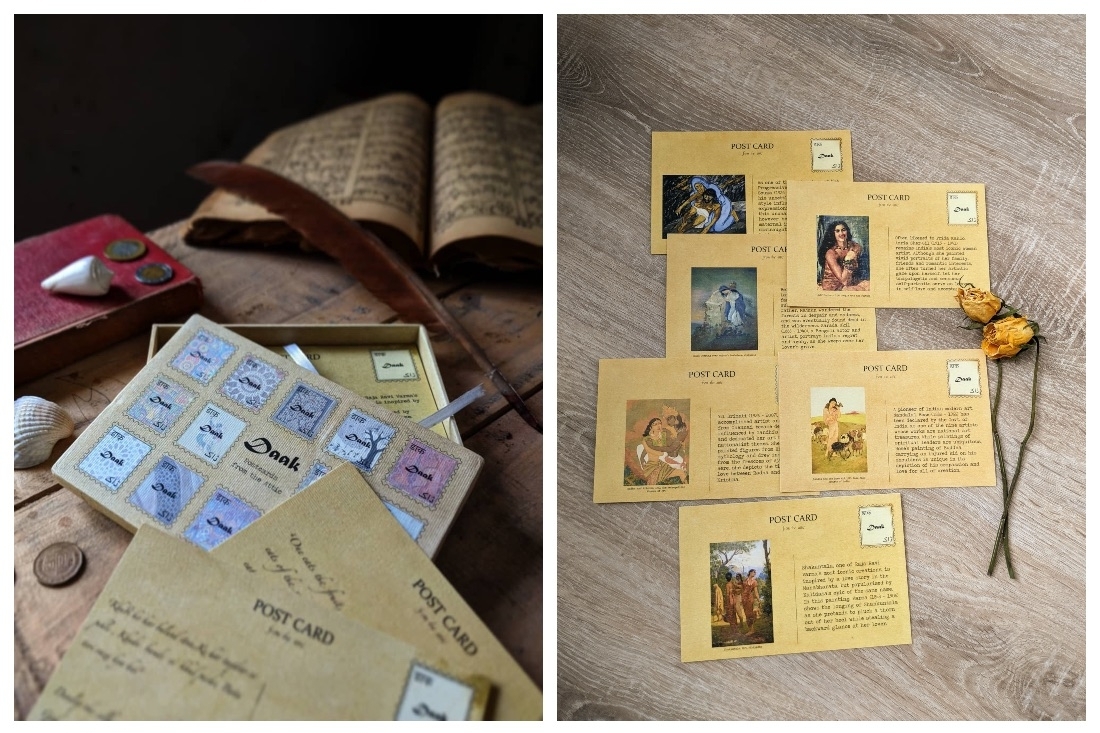

L: Daak Box Photo Credit - Mir Khubaib

L: Daak Box Photo Credit - Mir Khubaib

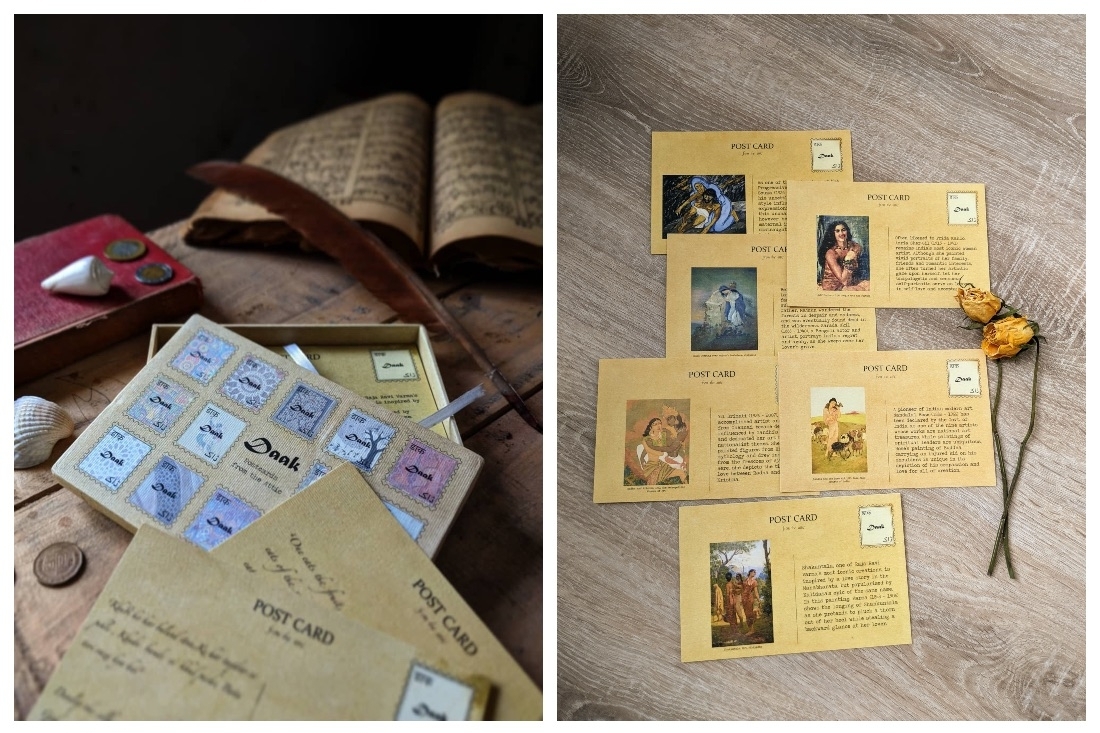

Daak: Postcards from the Attic is an exploration into the remnants of time and memory. Prachi Jha and Onaiza Drabu began Daak a few years after they met as Young India Fellows at Ashoka University, where they bonded over their shared love for art, poetry and literature. In their own words, Daak is an effort at collecting lesser known stories, artworks and ideas from the subcontinent. These works are then delivered to their readers’ inboxes every weekend, printed upon a tinted digital postcard, evoking imagery of a time that has since passed. Through their endeavour, stories, art, poetry, myth, legend, conversation and the everyday being of individuals, known and unknown, travel through the epochs to live among our present. From a weekly newsletter, Daak has now grown to become a repository of the profoundness of joy, love, loss, pain, uncertainty and even banality, expressed and found in dialects, cultural symbolism and folk traditions, distinctly of the South Asian subcontinent.

Daak is home to a large community intent on actualising, uncovering and appreciating the shared heterogenous cultural heritage of South Asia. Our frame of reference as South Asians finds meaning lent through this cultural storytelling, as the temporal gap between the past and the present slowly lessens. Each post is so painstakingly researched, that the love for literature almost becomes tangible and is shipped directly into your hands.

We spoke to Prachi and Onaiza, to learn more about Daak and their journey thus far.

How did Daak come to be?

At the Young India Fellowship, I (Prachi) was working on a similar project with one of the Founders of Ashoka University. The project did not materialise but the idea remained in my mind. I discussed this with Onaiza a few years later and she had wanted to do something similar, so it just clicked. We created a new visual identity and gave the project a whole new name, Daak, which for us represents both the nostalgia of the past and the anticipation of discovering something new.

What does your curatorial process look like?

We don’t have a method per se. In the beginning, we focused primarily on familiar names and languages. However, as our audience grew, we got a lot of incredible suggestions, resources and support from our readers. It has been especially useful to get suggestions and translations in different South Asian languages. It also helps that both of us are voracious readers and read literally everything that comes our way. We take turns curating the weekly newsletter and typically send it to the other person to have a look over. I (Prachi) take care of the editing while Onaiza is the person behind all the visuals and the aesthetics of Daak. We also try to strike a balance in terms of representing different voices and perspectives from South Asia.

Can you take us through the journey of how the project has grown over the years?

To be honest, we didn’t have a specific strategy. In the beginning, we were just excited to build a community of like-minded people, and to understand the cultural landscape of South Asia. As we have grown, we have also responded to our readers’ demands and interests. In our case, being open-minded and flexible worked in our favour.

From a niche audience, Daak has grown into a much larger community, especially on Instagram. Why do you think it grew so?

Instagram is such a frantic pace — there’s new content, trends and modalities every day. We feel like there is a longing to press pause and digest something slowly. Our page — with paintings, stories and poetry — gives people the space to stop, think and engage with the content in a deeper way. Perhaps that’s why we have the biggest follower base on Instagram.

How do you hope to reconcile the past with the present through Daak?

As South Asians, we already have many unique experiences and it is just a matter of drawing connections to the past. For instance, one of our favourite projects has been the curation of unique words in South Asian languages. These words not only demonstrate the range of emotions prevalent in our culture, but also shows us ideas, values and relationships that have been, and continue to be important to us.

Why the format of postcards? What is so important about remembering the days of ‘daak' or letter writing?

Both of us love the vintage aesthetic and have fond memories of letter-writing in our families. So the name and the visual identity came about quite naturally. The weekly newsletter for us was a way to evoke nostalgia and revive the practice of slow, patient and deliberate communication.

Writing and receiving hand-written letters by post has always been a very intimate affair. Do you think sending and receiving digital letters via inbox offers the same kind of intimacy? In other words, can the digital space ever be akin to non-virtual storytelling?

A few years back we would’ve said that no digital message can match the magic and excitement of receiving hand-written letters. However, as our community of readers has shown us, digital spaces can also be extremely intimate and personal. Our readers often respond to our newsletters with personal stories and anecdotes. Some time back, we ran a series on our Instagram page, where we asked our readers to share a secret. The response was unbelievably overwhelming and we got hundreds of messages from complete strangers who trusted us with deeply personal stories of love, loss and longing.

Out of all the newsletters you have sent, which ones have been your personal favourites?

Prachi: A recent piece I really enjoyed was writing about, and translating Kunwar Narain’s ‘Ek Ajeeb Si Mushkil' (A Strange Problem). It’s a funny and uplifting poem about love and acceptance, which feels very relevant in these times. Here’s the piece: http://daak.co.in/perils-love-kunwar-narains-poem-strange-problem/

Onaiza: Akhtar Mohiuddin's ‘Duniya te Afsane’, because I read in it a deeply layered Kashmiri story and it moved me to translate it, since it didn’t have an English translation. Here’s my translation of it: https://www.asymptotejournal.com/nonfiction/the-world-and-a-tale-akhtar-mohiuddin/

Your Instagram page features a lot of poetry, shayari and couplets. Can you share with us a poem or a couplet that has made an impact and stayed with you throughout the years?

We typically only feature poetry and art that really speak to us so, in a way, all the poems have struck a chord. But perhaps, two couplets that deeply resonate with our readers are:

dil nÄ-umÄ«d to nahÄ«ñ nÄkÄm hÄ« to hai

lambī hai ġham kī shaam magar shaam hī to hai

The heart has not lost hope, but just a fight that is all

The night of suffering is long, but it is just a night after all

-Faiz Ahmed Faiz

Jahan bhi azaad rooh ki jhalak pade

Samajhna wo mera ghar hai

Wherever you catch a glimpse of a free spirit

Know that is my home

-Amrita Pritam

What has been the most rewarding aspect of reviving lost artworks, stories and ideas?

Besides the personal gratification, the ability to reach out to so many people across the world and spark an interest in South Asian culture.

Where do you see Daak going from here?

We come up with hundreds of new ideas every week, and are now trying to be more disciplined about focusing on a few things at a time. At the moment, we are exploring themed online courses and new merchandise.

Text Devyani Verma

Date 15-06-2021