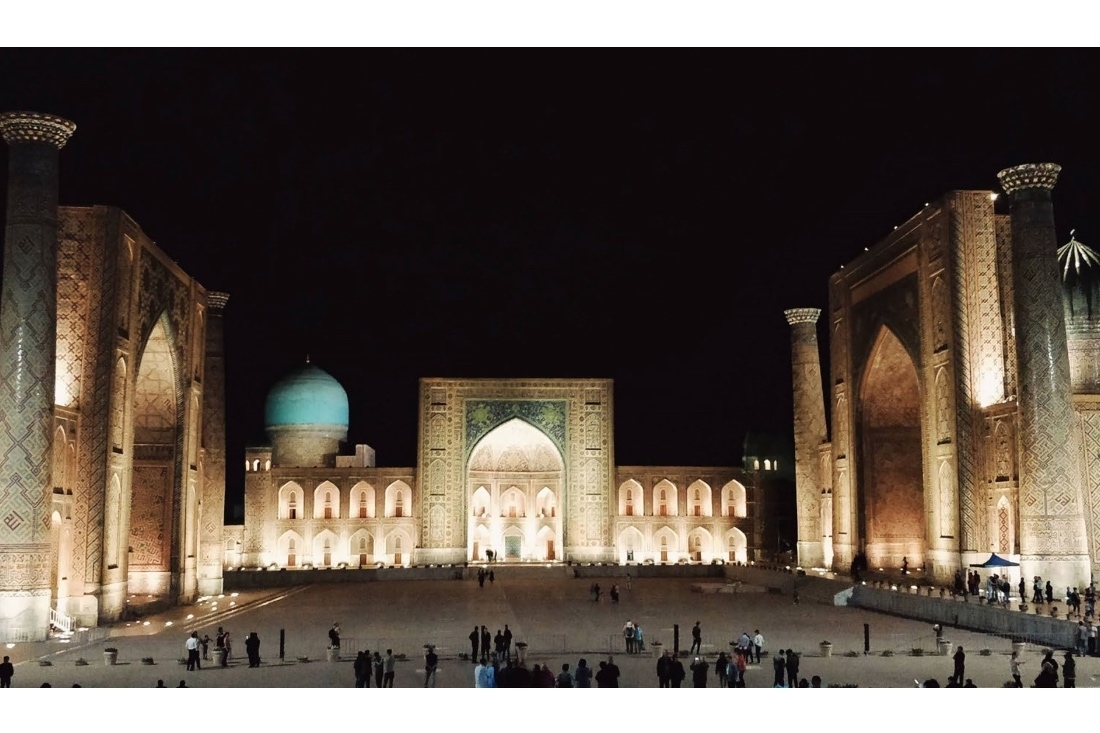

Samarkand’s Registon Square brilliantly lit up at night.

Samarkand’s Registon Square brilliantly lit up at night.

The man most of the world knows as Tamerlane and generally reviles, as a ruthless invader, is revered in his native Uzbekistan as Amir Timur. Statues of him in regal mien are the centrepieces of many public spaces. His real legacy, though, is in the huge gates, mosques, and other edifices that are the touristic cynosures of the country. While Timurspent much time expanding his empire, he also added greatly to its architectural, cul- tural, and spiritual life. Not all of what he built still stands, but significant monuments have been rebuilt or restored and form the spectacular centrepiece of Uzbekistan’s rich touristic banquet. The most famous of the landmarks is Samarkand’s Registon Square, which George Curzon (the same Lord Curzon who was Viceroy of India) once called ‘the noblest public square in the world’. We saw it at night, when it was brilliantly lit up, spread out like a luminous carpet below the vantage point from which we viewed it.

There were four of us on the trip – two friends and my wife Anjali and I. From the very first day, we got a welcome dose of the fascination with which people from India are treated. Walking around in the trading domes in Bukhara – ancient structures that were a fabled stop on the Silk Route a thousand years ago – we were greeted everywhere with the traditional hand-over-the-heart ‘Salaam’ and queries of ‘Hindostan? Hindostan?’ A trio of young college girls came up to us and got Anjali to sing along to Bole chudiyan, bole kan- gana. The Bollywood references varied with age – where the young girls went gaga over Shahrukh Khan, people from a generation previous raved about Mithun Chakraborty, while for those even older, the adulation was reserved for Raj Kapoor.

The singing college girls caught up with us again on our second night, at the mag- nificent Po-i-Kalyan (pronounced ‘Kalon’) complex. By the light of the ethereally lit Kalyan Minaret – till the 20th century, one of the tallest minarets in the world, at forty five metres – they tried out their Bollywood moves on us. In between these two encounters, we had seen so much of the ancient city of Bukhara: the massive Ark, the old citadel with its imposing mudwork walls; the Bohoutdin Complex that houses the mausoleum of Sheikh Baha-ud-din, founder of the Naqshbandi order and its adjunct necropolis; the Char Minar, a small but exquisite mosque-and-ma- drassah edifice with its minarets topped in turquoise.

The place I enjoyed visiting most was the Sitora-i-Mokhi Khosa Saroy, the ‘palace of the star like a moon’. The palace complex was first constructed by Nasrullah Khan, Amir of Bukhara, in the early 19th century and named for his beloved wife Sitorabony. After a couple of cycles of ruin and renovation, the current avatar of the place was built in theearly 20th century by Nasrullah’s great-grandson Alim Khan, the last Amir of Bukhara. By then, Russian influence had spread across Uzbekistan and is visible in the architecture of the palace as it exists today, fusing European features with local influences.

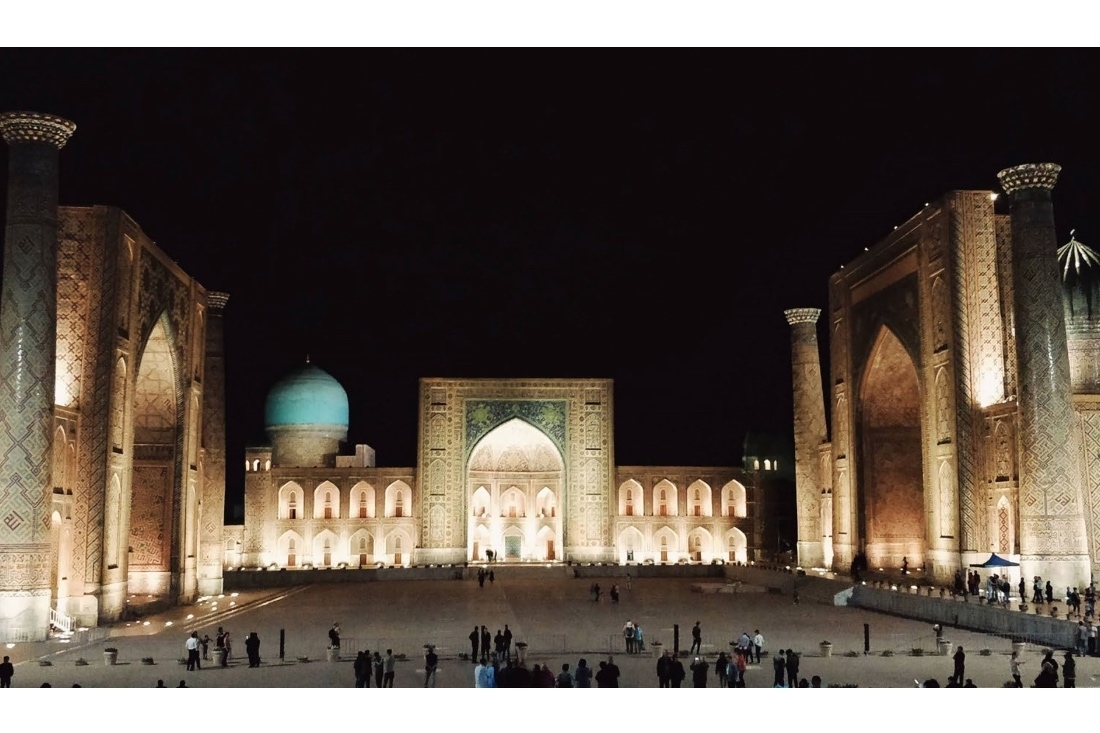

From Bukhara, we took the Afrosiyob train to Samarkand. The only high-speed train anywhere in Central Asia, it makes the Tashkent-Bukhara run – a distance of close to six hundred kilometres – in less than four hours, its kingfisher-beak engine slicing through the air at speeds up to two hundred and forty kilometres per hour. The sense of scale that I spoke of is most palpable in Samarkand. The highlight is the Gur-e-Amir, Timur’s mausoleum complex. A stately gateway, decorated with arabesques in shades of blue and orange, leads into the courtyard within which the mau- soleum building stands, flanked by two minarets. Inside, a massive vault-domed ceiling with intricate golden detailing overhangs a chamber in which rest five headstones, those of Timur, two of his sons and two of his grandsons. The graves themselves lie in a crypt below this chamber that is closed to visitors.

One of the graves is that of Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg, who ascended the throne at Samarkand at the age of eighteen. During his reign there was something of a resur- gence in Islamic science, especially in mathematics and astronomy. Ulugh Beg built a grand observatory on a hill overlooking Samarkand and astronomers here devised the Zij-i-Sultani, an astronomical table and star catalogue published in 1437 that was used by scientists in Asia and Europe for the next four hundred years. Among other achievements, Ulugh Beg determined the length of the tropical year with an error of +25s, more accurate than Copernicus’ estimate more than a hundred years later and determined the Earth’s axial tilt at almost precisely the value in use even today. Not far from Ulugh Beg’s Observatory lies the Tomb of Hodja Daniyar, the Daniel of the Bible. There are at least six sites worldwide that claim to contain his remains. This one, holy to all three Abrahamic religions, is rather extraordinary, the chador-covered sarcophagus about eighteen feet long. Legend has his bones continue to grow after his death and the container for them has had to be lengthened along with them.

If one’s talking about size though, the Bibi Khanum complex in the heart of Samarkand tops them all. Built in honour of and named for Timur’s favourite wife, the complex is fronted by a thirty five metre high portal that dwarfs all who enter. Inside, paved paths crisscross a courtyard dotted with trees. One can see, in this space, the pre- cursor of the char bagh scheme, common to Mughal horticulture. Restoration work was going on when we visited. An artisan working on a marble lattice called out the customary, “Hindostan?” My nod of assent was met with a happy yell of “Shahrukh Khan?” As a joke, I pointed to myself and said, “Shahrukh Khan!” He laughed, thumped his own chest and responded, “Abhishek Bachchan!” When you have no common language, laughter and Bollywood are enough.

Near Bibi Khanum’s mosque lies the sprawling Siyob Dehkon Bozori (the Siyob farmers’ market). Samarkand’s biggest market. It has row upon row of stalls selling everything from halva – the generic name for all sorts of sweets – through nons (the local flatbreads, related in name if not form to our naans) to fruits and vegetables, besides all sorts of household goods. Bazars such as this are a feature of most large cities in Uzbekistan. At the Chorsu Bazar in Tashkent, there is an extensive clothing section, where Anjali picked up a warm, stylish long coat for her sister to brave the Delhi winters, for barely 200,000 som (INR 2,000). Johon Bazar in Andijan is striking for the rows of vendors of various types of breads who line the front of the market.

But the mother of them all – at its grandest on Sundays – is Kumtepa Bazar in Margilon, where there’s nothing you don’t get. We picked up several varieties of the local cheese, called kurt (pronounced ‘kurrut’); gift packs of the dry fruits and nuts for which Central Asia is famous; the cardboard-backed caps that locals wear; even a set of the archetypal blue-pottery tea sets that are ubiquitous around the country.

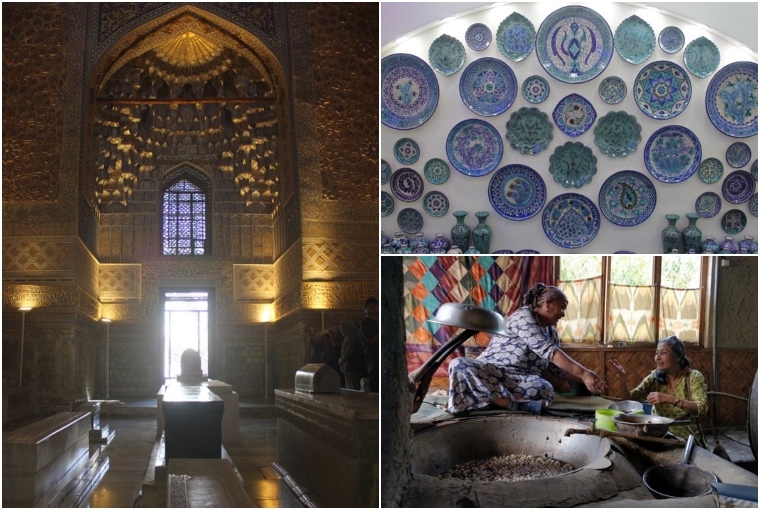

Much of those come from Rishton, a small town in the Fergana Valley, home to a large number of factories devoted to ceramics – local lore has it that the soil there is so suited to the process, it contains no additives other than water to produce the most wonderful clay. At one of these units, the Koron factory set up by Usta (a Persian title that is the root of the Urdu ‘ustad’) Ravshan Tojidinov, we were taken through this process of creation, the tour ending in rooms full of the most colourful pieces of pottery.

You can’t go to the heart of the ancient Silk Route and not come away with some silk. Our loot included scarves, stoles and jackets from the Yodgorlik Silk Factory in Margilon and silk paper made from the bark of mulberry trees from the Meros Paper Factory in Konigil, which Babur mentions in the Baburnama.

Babur’s antecedents, in fact, played a major role in our decision to include the Fergana Valley, where he was born, in our itinerary. It’s not on most tourists’ radar, but it was an enormously rewarding addition to our journey. At the Babur Literary Museum in Andijan, we gazed upon murals, done in a style reminiscent of Mughal miniatures – depicting his life, both as a child and a young man, in Uzbekistan and later as the founder of a new empire in the faraway Indian sub-continent. The Museum also houses an array of editions of Baburnama in various languages and vintages. Outside, a bronze statue of the man himself sits gazing out over the landscape where he grew up.

There’s an Indian connection to Tashkent, too – Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri died here in 1966. There is a wide boulevard named for him, next to which stands a bronze bust of him in an immaculate garden. After a ‘selfie’ stop at the statue, we used the Tashkent Metro to get around. The trains themselves are quaint and old-fashioned, but the ornately decorated stations leave you starstruck. The most memorable is the Kosmonavtlar station, with its space-programmed theme. The walls are studded with blue ceramic medallions depicting Ulugh Beg, Icarus, Valentina Tereshkova, Yuri Gagarin, and other cosmonauts, while the ceiling has been painted to resemble the Milky Way, with twinkling glass stars.

L:The cenotaph of Amir Timur surrounded by those of his favoured sons and grandsons at the Gur-e-Ami

Top R: Typical Uzbeki blue pottery on display at the Koron ceramics factory in Rishton.; Bottom R: Okhunova Inoyatkhon shows Anjali the gossamer-fine silk threads at the Yodgorlik Silk Factory

Disembarking from the metro, we went to a small joint called Old City for plov. Its name the root of the Hindustani word ‘pulau’, plov is a rice, meat, and veggie dish, cooked in large vats outside restaurants, such as this one, all over Uzbekistan. In most places, you can choose the meats and cuts you would like added to your plov. Every region has its own distinctive components and taste. My preference was the plov we had at the Magistra (‘Highway’) Restaurant in Bukhara, topped with horsemeat roundels and quail’s eggs, served with a tzatziki-like yoghurt and luscious tomato slices.

The sizes of helpings in Uzbek restaurants are enormous and the diet, meat heavy. The others in our group would wash it all down with unlimited servings of the light tea that accompanies every meal, while I preferred the sweet fruit compotes that are a liquid alternative. With dinner, of course, there were bottles of the best Russian and local vodka.

Upon our return, people asked us, “Why Uzbekistan?” To me, the romance of names like Samarkand and Bukhara were the triggers. Time and money both being limited resources, I would rather spend them on cultures that are hidden treasures. At a more practical level, Uzbekistan has much going for it. It’s within easy reach, barely a three-hour flight from Delhi. The exchange rate and the purchasing power of currency gives the rupee a bit of an edge, which is a rare thing. And now, having been there and back, I can say without hesitation that it was one of the most enriching experiences of my life.

This article was initially published in our June 2020 Bookazine. To read more grab your copy here.

Text Aniruddha Sen Gupta