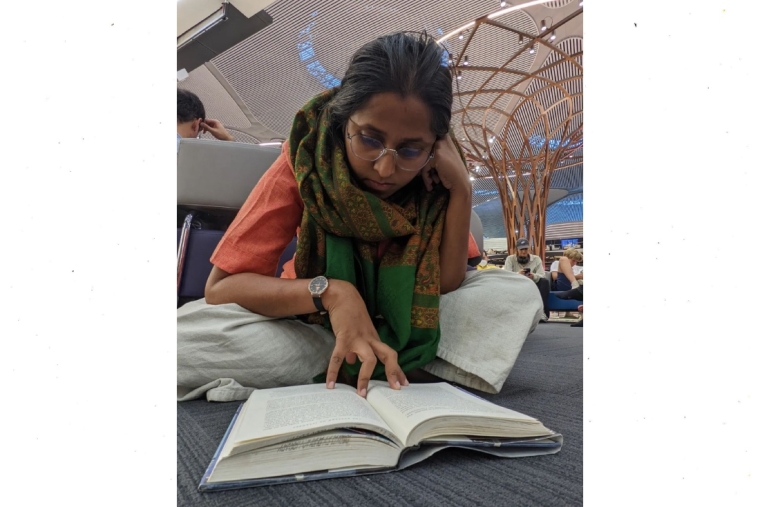

Surabhi Yadav, founder of Sajhe Sapne, an initiative that aids young rural women to build their careers and join the modern workforce, also picks up obscure feminist issues like time and leisure with her photo-project, Women at Leisure. She writes for Feminism in India, narrating her incentive: “Women at Leisure is a photo-project capturing women and girls in carefree moments of leisure, as a measure of freedom and visual reassurance of possibilities beyond restrictions of any kind, even if momentarily.”

We speak to Surabhi to delve deeper into her phenomenal work.

Tell us a little bit about your initiative Sajhe Sapne?

Sajhe Sapne ensures that rural women have a choice of a thriving aspirational career. Breaking intergenerational poverty, patriarchal and casteist cycle by making high-growth jobs accessible to rural women. Our key offerings include a community college model called Sapna Centers (Dream Centers) in villages which offer modern curriculums in regional languages and a pedagogy that relates to the context of rural women. We currently offer a 10-12 months long residential course in a village in Himachal for women coming from many different states.

Whereas most rural women in India do not get paid for their work, or have options for their personal and professional growth, we are here to set higher standards for education and employment opportunities that can be made available for them. Some of these career tracks include coding, teaching, project management. Most of the students of Sajhe Sapne are the first ones in their entire village to have pursued education after 12th grade and to have a stable salary. Sajhe Sapne's focus is on reaching communities where the notion of professional careers or growth pathways do not exist yet. The mission is to make career dreams real in most difficult places by making all world-class professional training courses available in everyday spoken languages to women in villages. The mission is to shift from "livelihoods" (income increment) development model to "growth pathways" (increase in skills, salary, say, support and sense of possibilities) for rural women in India.

What does the curriculum at a Sapna Center look like?

Sapna Centers are community college spaces at village level where women can come together to learn modern skills, question, explore, play, and find real concrete ways to earn. The focus is not just on helping rural women become job-ready, but actually lay the foundation of their careers, a long-term growth pathway. To do this, we focus on designing a rich learning experience. This experience includes curriculum for modern day workforce career tracks in regional context, as well as pedagogy that is full of play, exploration, and critical thinking. This experience has to be designed keeping the contextual realities of first generation college goers in mind, keeping in mind that many of them have had lived in acute scarcity growing up.

We have three career tracks at the moment for rural women to kick start their career in — project management, front-end web development, and primary math teaching. We plan to launch many more career tracks. Each career track includes four pillars: English, Career Intelligence (like negotiation, networking, professionalism, et cetera), Self and Society, and Specialized Skills (coding, teaching, et cetera). If you ever walk into a Sapna Center, there are no classrooms with walls, students lead the sessions by asking a lot of questions, there is singing, dancing, debating, discussions, and lots of learning by play and exploration.

It is no news that there is a lack of support and attention that rural India deserves, especially considering that most of India lives in villages. To me, more than the infrastructure, I think the worrying problem is that stakeholders for development in what is considered as mainstream, do not trust in the potential of rural people, especially women. I do not think India lacks the intellectual or monetary capacity to bring substantial innovations and development in rural India. For instance, most innovators in the education space do not imagine rural women doing complex sophisticated skilled-tasks but only repetitive manual labor, thus, we do not design the best education solutions for them. But it will only become a priority provided there is a trust in the possibilities and the potential of rural people, and that trust then would translate into political and business will. Urban India is pretty narrow in its worldview and approach to development. Investing in understanding and experiencing rural India with its complexity hasn’t made a cut in the priority for the mainstream.

Any plans of expansion?

The dream is to make Sapna Centers an integral part of villages across India. The hope is that this will shift the current reality of rural women settling for much less or almost no professional growth, to a new norm where they would be pursuing different interesting options for their own and others’ growth. The plan is to make as much knowledge that is needed for the new age workforce as possible in regional languages — machine learning, game designing, journalism, law, graphic designing, food businesses, et cetera. To give a firm nudge to big companies and organisations to open real doors for rural women in India.

Following suit, what are some of your ‘sapne’ for ten years down the line?

A strong policy advocacy and government support to introduce a new way of learning for youth and a firm foundation to create that system for rural women.

We are a team of women who are shifting the focus of the development agenda for rural women from their needs (silai-kadai-bunai) to their wants (opportunities to grow their skills, salary and social status). From repetitive, labor-intensive unpaid jobs to aspirational jobs they consider are dignified for them. We are transforming the way knowledge is produced and communicated — by curating and creating every high-quality professional skill curriculum into non-English languages. We are shifting the way professionalism is defined — very masculine norms of productivity and leadership — by making room for salwar-suit clad young rural women in offices with glass doors. With every student who has graduated from Sajhe’s first cohort, working as a young development practitioner, has made a crack in the glass ceilings made by their caste, class, gender, and geography.

The day when young women from villages earn stable salaries, create jobs for others, and take strides of professional growth is no more a news but a norm, we would have succeeded. There would be a day when mainstream perception of rural women wouldn’t swing between them being either objects of our curiosities (romanticised for their innocence) or subjects for their pity (so much pain!), but seen for their complex identities. When that shift in the mainstream gaze from their pain to potential happens, we would have succeeded. When there are easily accessible physical spaces for women to network, get skilled, find and create growth opportunities in villages, beyond schools, we would have been successful.

Text: Nandini Chand

Date: 15-12-2022