The world of the written word has always been inclusive. Even though the literary output might be shunned or the writer's identity hidden, literature has still managed to give space to voices that are marginalised or ignored. Writing has quite frequently become a way of not just escaping the immediate reality for many, but also of expressing themselves, and a tool for recognising who they truly are. As more and more LGBTQIA artists have risen to fame, so have the community's authors, who've used the power of writing to emanicapate themselves and their identities. Platform has also had the privilege to speak to such authors and learn more about them. In celebration of Pride Month, we revisit our conversation with LGBTQIA authors and provide snippets from their journeys of courage.

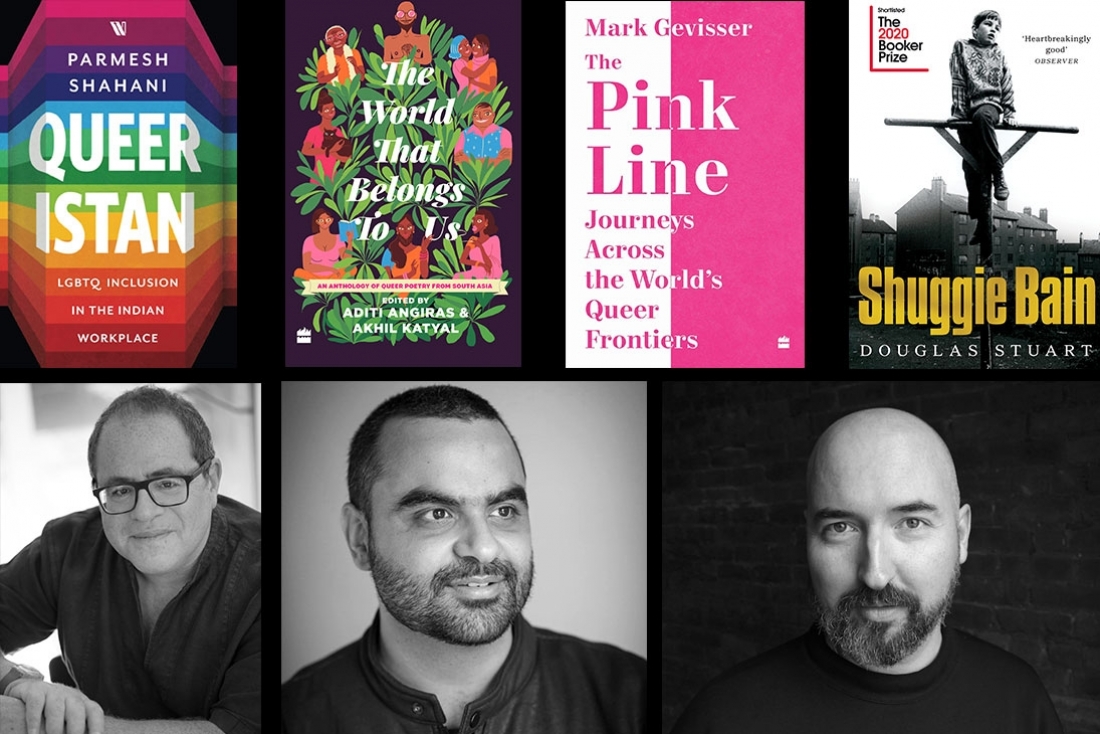

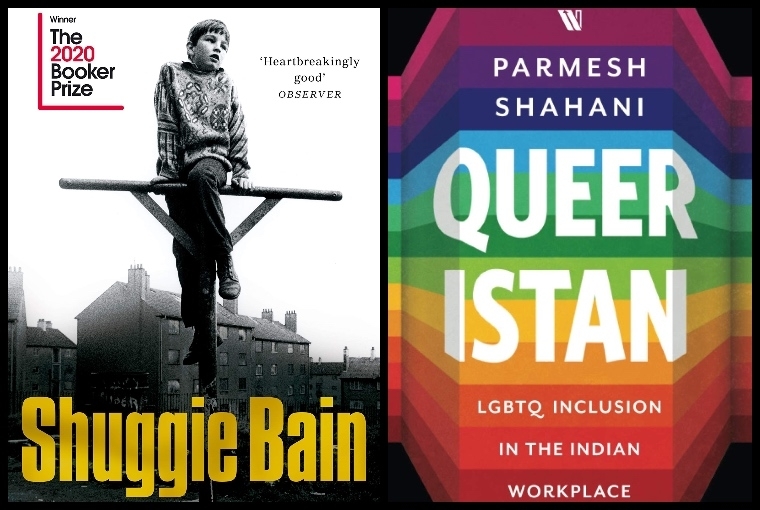

DOUGLAS STUART

I’ve been writing since a very early age. When you grow up with an alcoholic parent, you develop mechanisms — strategies, tricks — not only to survive their illness intact, but to try to save them as well. At about seven years old, on particularly bad nights, I would try to distract my mother from the drink by playing secretary with my pad and pen while she dictated her memoirs. Then from the age of sixteen I was writing really long, involved letters; corresponding with other boys that I met through queer message boards. There was a wonderful element of world building in that, and letter writing can tell us a lot about storytelling.

Growing up we didn’t have any books at home. As a young gay boy in an industrial ‘hard’ man’s world, books were seen as feminine, and therefore a bit dangerous for a boy to carry around with him. I owe my passion for literature to my two high school teachers: Mr Archibald and Mr Arthur, who saw that I was struggling and searching for a reflection of myself in the world. Then as a young man, I went on a self-guided journey of discovery. I tried to read as much working-class or queer fiction as I could. Now, as an adult, I couldn’t live without books. But I always feel like I got a really late start in life, and I feel like that’s a terrible shame.

PARMESH SHAHANI

I really want to create a more inclusive world for all my friends and colleagues, who did not have the same kind of privileges that I did. Over the past ten years, with the work that I have done and the people I’ve met, it's made me realise how a lot of work that I want to do in the future is about building infrastructures of equality at a systematic level. Because in my life, whatever happened was exceptional. It is not to say that I have not been discriminated against. I have been bullied when I was young. One faces micro-aggression all the time. When you grow up against a norm, whatever that might be, there is discrimination. But in my case, there was less discrimination than other people have faced.

So, a lot of the stories in my book Queeristan are actually optimistic stories. I wanted to write with a framework and viewpoint of optimism. There are enough stories on the news about harassment of LGBTQ people, suicides and parents forcing their children to convert. There’s a lot of bad stuff happening in our country, all the time, not just related to LGBTQ community. I wanted to showcase the range of good things happening as well — accepting parents, accepting workplaces, incredible LGBTQ community groups that are forming across the world. My point is, to create a better world, we need hope. And we can find hope in these small, multiple acts of change that are also occurring. I want people who read the book, to be charged with enthusiasm that they can imagine a better tomorrow.

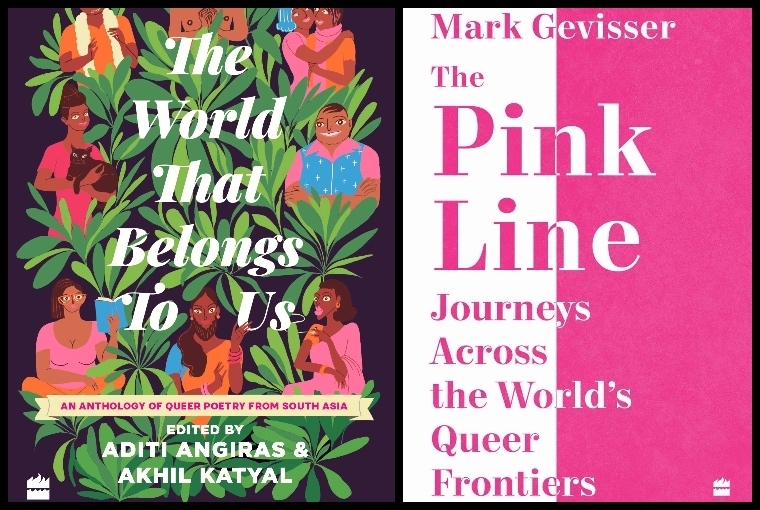

AKHIL KATYAL

I hope my readers take away the fact that there is no one guiding frame for queerness. That queer folks speak in a hundred tongues. That our life-worlds are as rich and different from each others’ as possible. That we desire from our worlds all sorts of freedom, not just of being ‘queer’. That nothing of this ‘freedom’ can be said to be abstract, real bodies are at stake. For instance, when the Indian government passes a transphobic bill in the name of supporting trans people, real people in the world stand to lose from it. The poems are a record of our failures and successes, as individuals, as movements, as lovers, as friends, and as community. Poetry gives an intimate window to our life-worlds. That intimacy should be read carefully for its honesty, for its gumption, for its ambition, and for its daring.

MARK GEVISSER

Same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa since 2006, and when my partner and I married in 2009, I thought about another marriage that year in the country of Malawi, to the north. Here, Tiwonge Chimbalanga and Stephen Monjeza were sentenced to 14 years hard labour for ‘carnal knowledge against the order of nature’ after they held a public engagement ceremony. It struck me that there was a new polarisation in the world, around what came to be known as ‘LGBT Rights’, and that a new global human rights frontier was being staked. I call it ‘The Pink Line’. This was as a result of a new global conversation about sexuality and gender identity unimaginable when I was a kid coming out as gay in the 1980s. Barack Obama has said that no social movement has brought about change so rapidly, and I wanted to understand why this was, and what impact it was having in different parts of the world, from India to Mexico, from Russia to the United States, from Israel to Egypt.