Photography: Laura Lewis

Photography: Laura Lewis

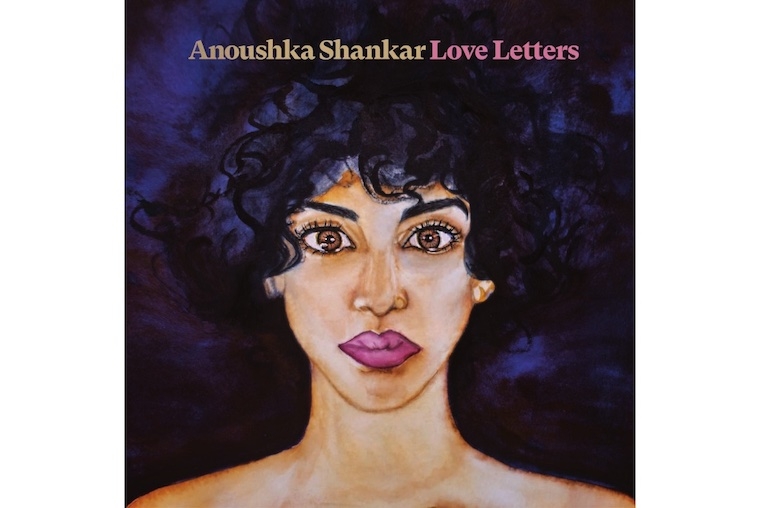

Sitarist, composer and producer, Anoushka Shankar’s new EP, ‘Love Letters’ is a meditative billet-doux to the world. ‘Love Letters’ emerged in the wake of a vital relationship coming undone. The emo- tions evoked are raw to the bone. The EP, which has been deservingly nominated for a Grammy this year, is layered with anger, pain and betrayal, hemmed in by a hope for personal healing. The music will resonate with anyone who has experienced the troughs of love, of fidelity gone awry, of living in its afterglow while attempting to piece one’s life back together.

Shankar’s sitar melodies are sinuous and poignant to a fault. The lyrics, modest in their being, sculpt a narrative that is grippingly honest. ‘Bright Eyes’ is steeped in anguish: ‘Does she feel younger than me, as you’re lying in your bed. Does she feel younger than me, or is that in my head?’

It’s beautifully balanced with ‘Lovable’, which is an anthem for celebrating the self and recognising one’s own light: ‘Am I still loveable, if you stop loving me? Hurling these seeds into a light of my own. Unfurling these leaves under a light of my own’. It’s a song where Anoushka lends her own voice for the first time. ‘Space’ is a sitar fusillade, revelling in self-reliance and resilience: ‘Now there is space for me, no more space for you’.There is a great deal of ‘female energy’ pulsating through the songs, owing to Shankar collaborating largely with fellow female artists, including singer-song- writer Alev Lenz, songstress Shilpa Rao, double bassist Nina Harries and the Afro- French Cuban duo, Ibeyi. It gestures back to how women come together in solidarity, expressing sisterhood in the midst of an emotional tragedy.

Platform speaks to the seven-time Grammy award nominated musician across continents via a video call.

You chose to call your EP, ‘Love Letters’. However, the music struck us more as one painfully about love lost. What led you to name it so?

It’s definitely a bit ironic and a little bit tongue in cheek, but it was the idea that the end of a relationship, is part of a pro- cess as well. It’s the idea that even that is part of love. The words that come out in betrayal, in hurt, in anger, in loss – all of those things are also being said as part of that journey of being in a relationship. So, in a bit of a morbid way perhaps, they are love letters, too. Also, I just liked the alliteration, I guess.

There is a tremendous sense of vulnerability expressed through the songs, which many can relate to. Was it easy to allow yourself to be so honest, open and generous with your feelings?

You know, when you’re so personal with your music and know that it helps reach someone else and they can identify with it, that’s kind of the point of the whole thing, isn’t it? It’s a personal catharsis as well. For me, there is something weirdly anonymous and disconnected about being this open in music, because it helps me think that there is a layer of remove. Like, I wouldn’t necessarily feel the same level of comfort of being equally open in an interview. However, writing songs in my own room, recording them with a couple of people whom I trust, is a personal process first. Then, there comes a layer of completion and then the music goes out to the world.

So, there is a huge time lag between being alone or with close friends and expressing enormous pain, to later on releasing it to the world. By the time the music comes out, it doesn’t feel as personal any more. It’s hard to explain. Also, after playing the first performance and the second performance, even that process of performing the same music live, which earlier may have been very raw, no longer feels raw. It doesn’t feel like I’m cutting myself on stage every night; it’s more like an act of simply performing the songs. So, it doesn’t feel difficult in any way. Having said that, over the years, it’s probably been a long process for me to get increasingly comfortable with myself and become more and more intimate. My earlier music had very clear boundaries estab- lished, but over time, I’ve come to trust my vulnerability, because I think that’s what people really like to hear and connect to.

The lyrics in the songs like ‘Bright Eyes’, ‘Wallet’, ‘Lovable’ and ‘Space’ come across as very private thoughts, akin to diary entries. What was your process behind writing these lyrics and composing the music?

I tend to write lyrics in a diary, even if they aren’t literally my diary entries (which these ones are not), but they are written in the same way. It’s pen and paper, which is so different from anything else, written in a diary; and it’s lying on the floor, on a carpet, rather than sitting at a desk. For me, it’s really a more intimate process of writing.

I think it also involves a layered process. When I first start writing a song, I’m not thinking of sharing it yet, because that will inhibit me. I write as if no one is ever going to hear it. Then, there is a layer of choosing to share that with a co-writer or a band member as part of the song-writing process. Here, some amount of confidence or checking happens automatically: Does it feel too raw to read these lyrics to my friend who is singing with me? If it does, I probably don’t want to release it. However, if it feels comfortable doing that, then I gain the comfort. And usually there is a process of figuring out whether a certain line feels too on-the-nose, which we might have to soften a little.

Also, I think there is something really comfortable about saying things in art because they are not necessarily direct. The songs may not necessarily all be about me – some of them maybe, but some of them will take on broad experiences of other women around me or other people, so it becomes a little bit collective. When I feel confident that it is hitting a nerve or reflecting a collective experience, then I start to feel like the song has a purpose. Then it no longer feels that I am just airing my laundry. The song just expresses something we all may have felt at some point in our lives.

Could you give an example?

‘Wallet’ is a great example of an experience I haven’t really heard being articulated in a song. It expresses what it’s like to be a mother of young children while going through a break-up or what is the role of father in this context? As I said, these things may not all be directly about me, but as I started writing, there were just so many women who were relating to it and so many friends who had similar experiences. So, then it becomes a collective experience.

In Lovable, you sing for the first time. Why didn’t you do this earlier?

Part of me is kicking myself for not doing it earlier. At one level, I felt that I had the potential to sing, but that always scared me. I have professionalism to a crippling extent and that fights with my inner desire to be vulnerable and authentic. All this stuff, this fear of failure, inhibits my creative process. It makes me think, ‘Oh god, I’m known for being a really, really good sitar player, so my singing can’t be average. My sister is Norah (Jones), so I’ve got to be amazing. I can’t sing badly’. So, in the past, when it came to singing, it always felt safer to step aside and that became the narrative I told myself.

The truth was that I probably wanted to sing for years, but when people asked me during interviews, ‘Are you ever going to sing?’, I’d always give the same answer, ‘Oh no, I’m not a singer. I play the sitar and I prefer having someone else sing’. That wasn’t even necessarily true, but I always felt that I wasn’t good enough, so it felt safer to give the song to someone better.

What changed your mind?

I think the fact that Love Letters is an EP and not an album, allowed me to feel less pressured. Also, the fact that I was working with women who were friends helped. To be honest, compared to working with a lot of men (even though I work with truly lovely men), it was a bit more of a ‘yes’ environment for me while working with women. They’d say, ‘Let’s just try it. Let’s just see how this goes. Let’s do this again’.

Whereas, I’ve been in situations with men (whom I love), who might not always be so open or exible. So, even the singers I was working with, like Ayanna (Witter Johnson) and Alev (Lenz), gave me tips, ‘Oh, try singing like this’ and the experience just felt very safe. In fact, when the lead from Ibeyi and I were writing the song ‘Lovable’ together, she said that I had to sing on it and it just felt right. I’ve done a bit more singing since then, which feels really good, so it’s something that is growing on me more and more.

Photography: Laura Lewis

Could you say that as a musician your music has evolved with every milestone that has marked a significant development in your life? Say, the passing of your father, Pandit Ravi Shankar, motherhood, or the after- math of your break-up?

We see all that in hindsight, don’t we? I would say, yes, there definitely have been formative experiences and periods that have impacted me as a person and then impacted me as an artist. So, sometimes there is a bit of delay in the art process because it happens to the person (me) first. In April 2020, you were to celebrate your father’s birth centenary. It would be the first time your sister, Norah Jones and you would perform together on stage. However, due to the pandemic, things got postponed. In broad brushstrokes, could you describe what you had planned?

We were going to do a series of concerts around the world, including India by the end of the year. However, at the moment, everything has either been cancelled or postponed. The only show that has an official rescheduled date as of now, is the one that was going to happen on his actual birth centenary in London in April, which has been pushed to 2021.

It was in some ways the biggest show I’d ever planned. It was something that felt absolutely unique, new and exciting to me, both as a creative ambition and a personal fulfilment. The plan was to put together an ensemble of many of his key disciples, a bit similar to the kind of work my father did himself in the 1970s, that is, creating an Indian orchestra and playing on a very large scale.

If you’ve ever seen the concert for George (Harrison) that we did in 2002, it’s a bit similar in that vein, but this was the first time I was putting it together myself. I spent a lot of time going through my dad’s catalogues, choosing my favourite music, rearranging all of it, putting together an ensemble. I was having an amazing experience going through his work, writing out his notations and getting it all ready. Alongside that, Nitin (Sawhney) who is a very dear friend and a key collaborator, was going to take part. So, planning the music with him, while also discussing the music with Norah about what we’d be singing and playing together, was special. It would’ve been a show that has never happened before...and then it didn’t happen!

What are some of the changes that you have witnessed within the music industry due to the pandemic?

On the whole, it’s been really tough. I think everyone has lost their sense of income and are wondering how to get it back. For some people that’s been okay. Like, if you’re getting composition gigs for television that is still being made, then good for you. However, if you’re predominantly a live musician, then it’s all gone.

As always, with all challenges, some interesting innovation takes place. So, it’s been really cool to watch how some people have taken to online platforms. When you see the sort of videos Jacob Collier is making while playing eleven different instruments, for example, it’s amazing. At least, this pandemic has happened at a time where we have the technology, which allows us to continue recording music with each other. I get things sent to me from other people and I’m sending things to other people, and so, we’re still ticking on. In fact, I attended a couple of online ticketed concerts. That stuff gives me hope, where people have started to hold audience-free shows, filming them with good quality and good sound, so that people can pay a little bit of money, support it and watch it live. So, you still get that special feeling of watching something like a concert, but from your home. That stuff is interesting and is a potential way forward for now.

Finally, what lies ahead for you?

I’ve got a big festival which will take place in November 2021. It’s at The Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, Germany, which is an incredibly iconic venue. Just in the last couple of years they’ve started doing the Reflektor series, where an artist curates a long weekend. I’ll be doing that next year. I’ve also got a few gigs in the diary, based on whether they go ahead or not. Other than that, I’m perco- lating the new album. I might be singing in it, but it’s feeling more instrumental to me right now.

Lockdown has been really interesting. I’ve been going on walks and there has been a lot of space to connect with nature. I’m having a love affair with trees. They’ve been a massive inspiration to me. I’m trying to figure out how I can play that feeling in my music. To be able to see a beautiful three hundred year old tree and touch it and feel its connection – it makes me wonder, ‘Okay, how do I play that? How do I translate that into music?’ What I am obsessed with at the moment is trying to find that feeling in my music.