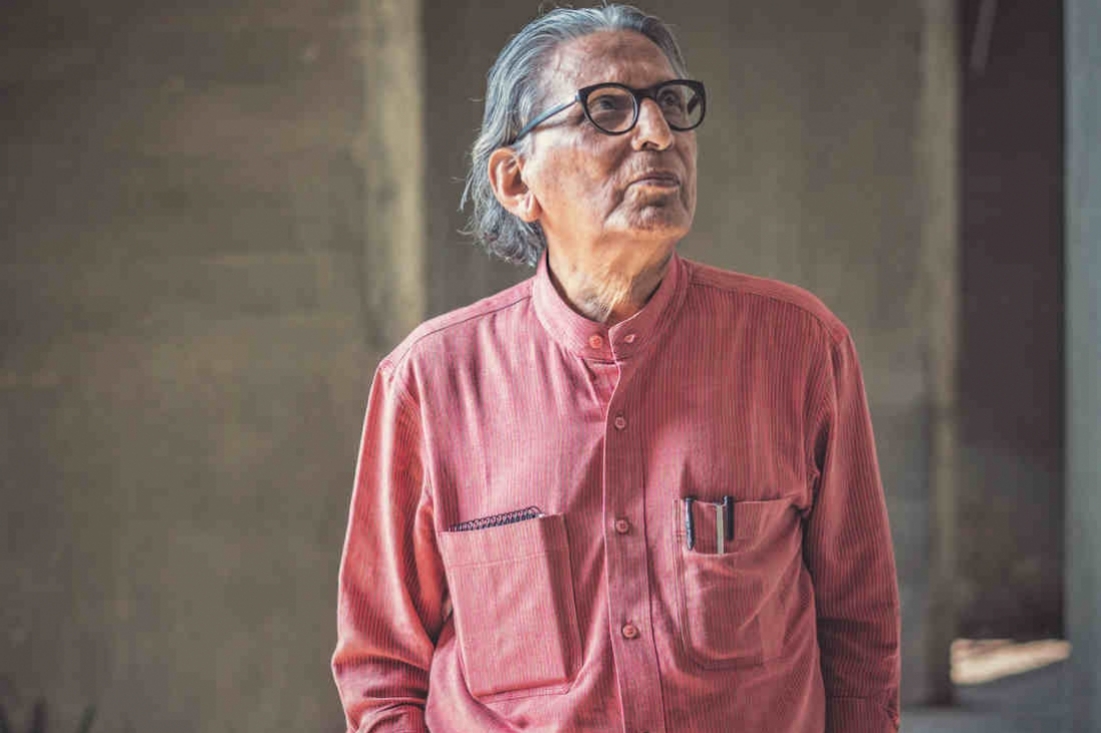

Photography Fabian Charuau

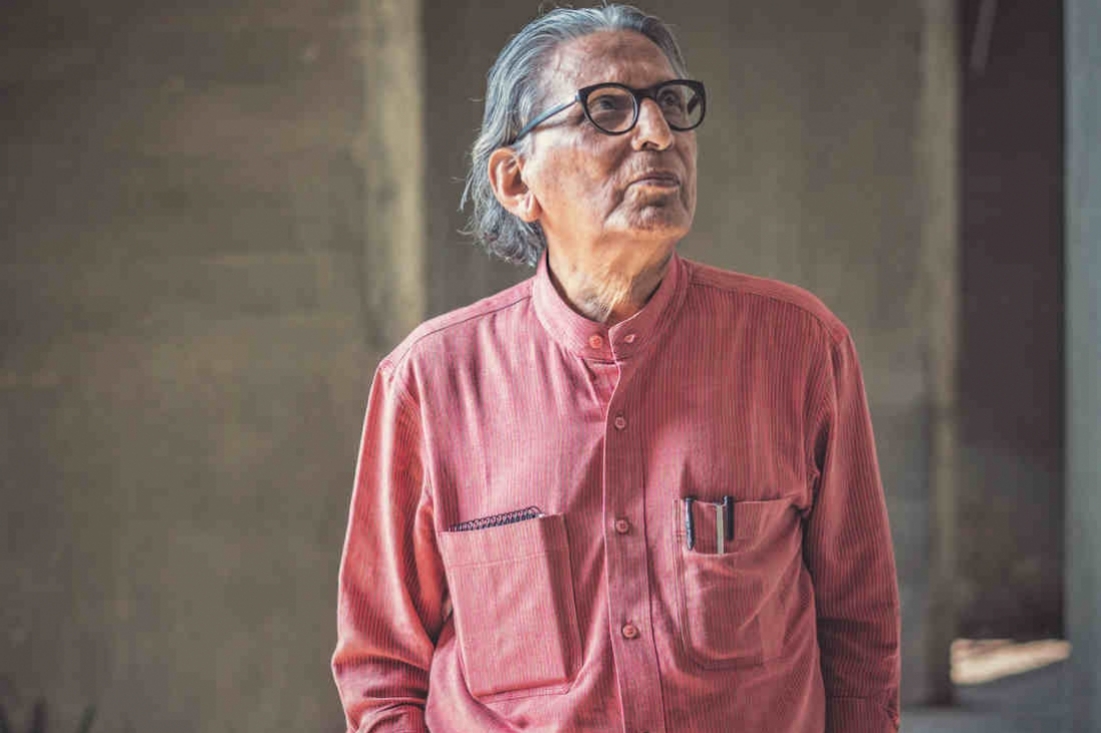

Photography Fabian Charuau

Balkrishna Vittaldas Doshi is Winner of the 2018 Pritzker Architecture prize, (it is not the Nobel Prize for architecture; it is considered the most important award for architecture). B.V. Doshi is a thinker and a teacher whose work is invaluable to the narrative of Indian architecture. He was also the Founder Dean of the famed Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology in Ahmedabad, one of the many institutions that he was deeply involved with. His other important work is in pioneering sustainable low-cost mass-housing projects in different parts of India. He belongs to an eminent group of great Indian architects who are responsible for creating an identity for modern Indian architecture, working during a time of both hardship and excitement, when creating heritage did not mean building big ghastly things in the middle of the sea. Or on land.

Mr Doshi is currently busy with a retrospective of his work that opens at the Vitra Museum in Germany, soon. He lives and works in Ahmedabad, a city he loves very much, and to it he has contributed many important buildings – The Tagore Hall, L.D. Institute of Indology and L.I.C. Housing complex among many others. This meeting took place at Sangath, Mr Doshi’s office, a research centre and cultural space in Ahmedabad, which is also considered a great piece of architecture.

With a warm handshake, he asked me if we had not met before. I almost said, yes. As we sat down for our chat, I fidgeted with recording devices, phones, notebooks and pens. Mr Doshi said, “Do you want to check them again?” and started interviewing me.

Excerpts from the interview:

NU: Could I please ask you a few questions about your family and home?

BVD: I have a question for you. How come you are so interested in portraits?

NU: I make as many portraits as I make fake landscapes.

BVD: How are landscapes fake?

NU: I use a city, a street, or a park, for example, and populate it with things that might have existed there, like a set-up.

BVD: So you add what you miss, or long for.

NU: Or what I see coming.

BVD: That is a good thing. You are putting the “missing links” into your works. Is that right?

NU: I have been told that they are sad and lonely.

BVD: No, what you draw is different from what they convey. I am talking about the idea of filling the gaps and making them into something that you had thought of, or imagined.

NU: Yes, maybe.

BVD: That is what I do too.

NU: Yet you remember to maintain your belief in the goodness of humankind and your Gandhian outlook. So it is different.

BVD: You have had sad experiences.

NU: I don’t know. Apart from my home and my little family I find everything else terrifying and objectionable. Coming back to Ahmedabad after all these years has been horrifying in that sense. But you talk of Indians as a people who are innovative, frugal and adaptive. Do you also see us as imaginative?

BVD: By saying that we are frugal I meant that we understand the uncertainties of life and our way of life is simple: without getting into too many obligations. For example, if you are a family of five, you have to provide for them, educate them and so on. You are thinking about the future and about what you have, so that you can take care of their needs over time. You think of how to make it simple. With frugality, you get the certainty of meeting these needs because your attitude isn’t large. Frugality isn’t poverty; it is living with grace.

NU: Expanding on that thought, do you think that we are also happy with the abstract? God is an abstract concept according to our philosophy, like it is in many other philosophies. Do you think of us as a people who are happy with the idea of the abstract?

BVD: Naturally. When you believe in it, then it isn’t abstract. Abstract is what you don’t believe. For instance, this thing here (pointing to the recording device) is recording our conversation and if I ask, it will play back. For me, it is a real thing and it would be abstract if it weren’t working. If you can allow something that is “non-material” to express itself, then it becomes real. That is what I mean.

NU: But the abstract is a good thing, no?

BVD: Yes.

NU: For thirty or forty years after Indian independence our institutions were built not with insulated thought but with a lot of the distant future in mind…

BVD: Everything one builds should be free so that there is room for modification and hope for change. That is what life is about.

NU: And has that undergone a change in the recent past? Along with people’s view of life, living; their notions of the future and achievement?

BVD: It is difficult to talk about someone else’s life. But I would say that I have not seen anybody who does not dream of the future. His idea of the future might be different from yours, everybody lives in their own worlds or they wouldn’t be there. They would not be with their parents, get married or have children. The future, an abstract idea will one day be realized for them and that is the aim of their pursuits, and that is why they are the way they are.

NU: And it would be wrong to pass judgments on that.

BVD: You can’t judge that.

NU: Local arts and craftsmanship was integral to institutions and buildings till our recent past. It was also a question of pride and identity, and your works are perfect illustrations of these values. Now there is a complete disregard for these values and that has led our towns, cities and streets to look the way they do. What do you think has changed?

BVD: Uncertainty and lack of hope has given rise to thinking less of what is not, or what is not immediate. When you think about what is not immediate, you don’t have vision, and when you don’t have vision, you don’t talk about celebrating that vision. So, arts and crafts don’t come into the picture.

NU: I have seen a photograph of you with your children and grandchildren sitting around a centre table having tea. It’s a lovely image. For you, family has been the most important thing; the first building block maybe…

BVD: Absolutely.

NU: Do you always start with the idea of “home” whether you are designing a private residence or a large institution?

BVD: Always. I have a garden and I don’t think that I ever stop thinking about it. Then if you go to a plaza you think about the people too. I don’t think that we ever stop thinking of our surroundings. Even if someone wants solitude they would still like guests sometimes, and the world is based on communication. I would say that the question to ask would be if people think beyond themselves these days.

NU: You listen to a lot of classical Indian music. Who are your favourites?

BVD: Bhimsen. Ravi Shankar. Kumar Gandharva.

NU: And among other forms of art?

BVD: My daughters have all done several years of dance, so there is that, and music. I was a student of painting. I collect antiques and sculptures and so arts and crafts have always been part of the family. Just look around the room and you will find many works of art from all over.

NU: You draw so many references in your talks, conversations and interviews, and yet they are easy to grasp and de-mystified –

BVD: What is de-mystification?

NU: You speak in rational, simple terms..

BVD: Theories exist to justify life and I don’t need to justify life. I have been dealing with students all these years.

Khushnu (BVD’s grand daughter who is also an architect): I think it’s also because of the way he is. He is very approachable He has absolutely no ego. So, when anybody comes looking to learn from him. He instead looks at what he can learn from the person. It is not about what he can teach. It’s like he wants to learn.

BVD: I am actually trying to discover and analyse you. It is true. Who is interviewing whom? (lots of laughter) No, it’s my old habit of mine. Nothing comes by chance and when something appears, that is my belief, that there is some message. I always try to find out that what could be that message, which is important for me at this moment, so that I can go forward. So no instance is there where I would argue negatively, I would stop but I would try to elaborate it and unfold it. And in that unfolding, I will get something more. So always this is the idea that I have come here to discover and I must perpetually be in this state of discovery and happiness or inquisitiveness. So there is never an incident, which I take as a problem, or an opposition. It is an opportunity. In my childhood, the door of my grandfather’s house, in the evenings was alwats slightly open. The moment the lights are on, in other houses people would lock their doors; in our house the door was unlocked and left open because you never know when the goddess of knowledge and wealth will enter and I believe that.

BVD: Oh you make very nice sketches (exclaims looking at my sketchbook).

NU: I began this sketchbook the day I read about your winning the Pritzker prize.

BVD: How long have you been doing this (keeping a sketchbook)?

NU: I have one with me almost always.

BVD: Nice. What are you searching for in these sketchbooks?

NU: I fill them with everyday things – today it will have our conversation, the book that I am reading and so on.

BVD: They really are nice sketches. I think your book is designed that way, it is an interesting book.

NU: I think it is meant for film-makers and animators to make storyboards and key frames.

BVD: Okay, okay.

NU: Would you be writing another book?

BVD: I think so, yes. But about what, I don’t know. I think I would like to write an imaginary interview where there are six or seven people and they enter one by one and a free-wheeling talk talks place, This is something I like – then I can make an exit and go talk about it with my family. It is like a ‘yatra’, a pilgrimage from stage to stage. You go on discovering and unfolding.

NU: A book that is a conversation. Like the film, ‘My Dinner With Andre’. That would be very lovely.

BVD: I don’t know how to do it.

NU: You draw, but have you also sculpted?

BVD: No, when I make my models they are like sculptures…

NU: Like during the Gufa-time?

BVD: Yes, models of buildings are like sculptures. Form, location and place are very important to me.

NU: Do you still build homes or is it just institutions now?

BVD: At the moment I am not building any homes. I used to do both.

NU: I have one last question before my hour with you is over.

BVD: Oh, the hour is over?

NU: No there are ten minutes left. In a recent documentary you ask regretfully “what is our heritage now?” This was at Sarkhej, I think. You stopped with that. Would you like to say more? I ask because it follows from the earlier question about our cities.

BVD: Every culture leaves behind its footprints. Some last longer than others. A house might disappear but a temple or a monument in the pols of Ahmedabad will stay. When you revere something you want a place for it to be manifested. Temples and mosques manifest the presence of god, and with the rituals, they become a place of reverence. This heritage is now missing because we don’t think that it is our job to create something that will stay. There are no stories, messages or beliefs. So without these what are the buildings for? Let us take Manek Chowk in the old city in Ahmedabad for instance. It might not be significant but it has created a history of complete transition over time: from morning, till evening, till night, it becomes a public space. And supposing all that goes away, the memory will stay. But if we change the buildings and their configurations the memories will go away too. There is fragility, temporariness, depth and a magnet that is inviting, which is what monuments are. And then there are the stories and myths. Things happen there – couples would remember the time they went to Manek Chowk where a love affair began. These things don’t happen anymore, our lives are not connected to the public realm anymore. We don’t connect it to anything other than ourselves. I made the Doshi-Husain Gufa as a gesture; a myth. Today it is a hub with a café and a gallery and so on. Then there is the image of the cobra on top and it tells a story which you may not know. You enter the gufa and you have yet another story. I think that all these things come together and create heritage.

NU: It is also a time when people’s rules of engaging with their lives are changing.

BVD: People are not living their lives, they are toiling.

NU: The monumental aspect of buildings –

BVD: Reverential aspect. I never use the term ‘monument’ because it changes the scale of things – Manek Chowk will not be a monument, then. Heritage is something you revere because of your ancestors, communities and long associations.

NU: This idea of heritage was a big part of Nehruvian vision, no?

BVD: it was a big part of our culture and history. It isn’t there now.

NU: It used to be institution-building then. Now it looks like it is institution un-building.

BVD: Yes.

Text Nityan Unnikrishnan