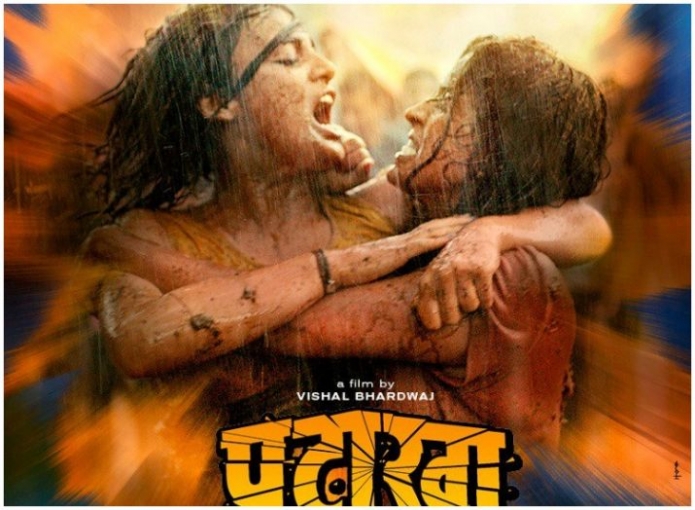

Be it transcreating Shakespeare into a rural Indian tale, or making excitingly progressive cinema for children or even making a short film to raise awareness on issues like HIV/AIDS –producer, director, writer, composer and singer, Vishal Bhardwaj has already established his own unique vocabulary in almost every aspect of cinema. With a critical, cult and mass following, this forty-something filmmaker has already dissolved imagined boundaries and is currently making ready his much anticipated and awaited film, Pataakha. In an exclusive conversation with the man himself, our former Guest Editor, Anurag Kashyap (better known as an infant terrible of sorts) reveals the tracks that made this Meerut based cricket-loving boy into one of the most versatile of men in Indian cinema today.

AK: Let’s go back to your Hindu College days; your focus at that time was entirely on cricket. How and when did music and cinema begin to feature in your life?

VB: My father was a poet and a lyricist for Hindi films – he had written songs for composers like Laxmikant-Pyarelal and Usha Khanna. My brother played the mandolin, my sister played the sitar, but I wasn’t serious about music at all. But there must have been a composer in me somewhere because I used to constantly compose my father’s poems. One time, my father wrote a song for a film called Yaar Kasam directed by K Prasad, starring Marc Zuber, Zeenat Aman and Raj Babbar. My father gave me Rs. 200 and asked me to take the Dehradun Express so I could make it to the Mahurat of the film. When sitting with the director and the team over drinks, my father mentioned that I had composed a song. They asked me to sing it and instantly they called the film’s Music Director Usha Khanna and told her I had composed the mukhda. Before I knew it she was asking me if she could use it for the movie. She then composed the rest of it and the song became Khudha Dosti Ko Nazar Na Lage. That was the first time I realized that I could do this as well, it gave me a sense of confidence.

But music was never part of the plan. I was part of the UP under-16 cricket squad. We won the final but they didn’t let me play because I was from Merut, so I never got preference and I was always sitting out. I was very frustrated. I even repeated class 12 to play for the team again and that’s when I became the Vice Captain of the UP Team. Our first match was with Delhi. My closest friend at the time, who used to sit out with me during matches, was not selected but I was, even though he was the first standby. He tracked down my papers and said it was illegal for me to play since I was repeating the year, he even got an order passed by the school saying I should be thrown out of the team and just before the match I was thrown out. I was so heartbroken because I had chosen to drop a year just to play for the UP team. Later, in an exhibition match with Gursharan Singh, Tilak Raj and Manoj Prabhakar, I made a solid 50, that’s when Gursharan told me to come to Delhi and try out for the Hindu College team. So, I decided that I would go try out for the Delhi team instead.

AK: So, you got admission into Hindu College through the Sports quota?

VB: I came to Delhi, played the trial matches and got admission but I didn’t get into the hostel. Initially I stayed at the Ramjas hostel, later we bribed someone with Rs. 5000 and got a room in the Hindu hostel. Since Gursharan was playing for India, Raju Sethi became the college team captain and was also in the hostel, he used to give me Rs. 200 over the weekend and send me (his junior that time) to get beer for him from Kashmiri Gate. We became friends over time and he told me that I wouldn’t get a chance to play because I was a batsman and the team already had a solid batting line up. He suggested I become a leg spinner so I could become an all rounder and have a better chance. I took his advice very seriously and became a leg spinner. I made it to the line up. Exactly two days before the match while bowling to Gursharan, I broke my thumb. Till date my thumb is like that. And I couldn’t play the match and had to sit out again!

It was a very frustrating time and to add to that my father died the same year. College was almost over. Sometime during all of this I fell in love with Rekha. She was the star of the college. Everything happened simultaneously. Cricket became very hard to keep up with after my injury. I didn’t have any money, I was in a very bad financial state and I knew I couldn’t sustain myself like this. I wanted to be rich and famous. And I realized the only other way to get there was to become a music composer. Thanks to Usha Khanna I felt this was possible. I didn’t have too much knowledge of music but I started discovering the composer in me. I made friends with people involved and interested in Indian and Western classical music. I was soon exposed to instruments like the violin and guitar. Rekha was an Indian classical singer and through her I realized that to become a singer I would require too much training and riyaaz – that wasn’t for me. But I also realized that as a composer I could just get someone else to sing it for me! And that’s what I started getting into more and more.

AK: When and how did your big move to Bombay happen?

VB: I made my first song in 1984 with Asha Bhosle, I was 19 and in second-year college. The film was Veham and this was a copy of House With A Yellow Carpet. I have been recording for 26-years now. But I began during the Doordarshan days. I used to do songs for a few music programmes and I used to play the harmonium for light programmes as well. I remember ghazals were very popular at the time. In fact I used to also play the harmonium at the UP Pavilion during trade fairs at Pragati Maidan in Delhi. At the same time, my brother was trying to be a film producer in Bombay. He didn’t have any money either, so he had his own struggles. I wanted to move to Bombay but he was very reluctant about me trying and said ‘tera kuch nahi ho sakta’ because he felt I was too classical with all the ghazals I used to compose at that time. He told me to stay and even offered to open a video library for me saying it was good business. But I ran from it, I just didn’t want to do that. I decided I would make a living myself. In Delhi, there was a recording company called CBS and I got a job there as a Recording Manager. My brother suffered from a heart attack in Bombay and then I just had to go. I asked for a transfer and I got it. I moved to Bombay and worked here for two years in CBS, which later became Pan Music. No one used to take me seriously as a musician back then because I was a Recording Manager and my job was to make vouchers and collect money.

AK: How and when did your association with Gulzar Sa’ab start?

VB: I met him for the first time in Delhi when he was recording and making music for Amjad Ali Khan Sa’ab’s documentary. I was working in the same recording studio and I overheard someone say ‘Gulzar aa raha hai aaj raat ko humare yahan’!’ So I sat down and waited at the reception. The phone rang and I was the only one there – it was a call from Gulzar asking for directions. So, I ran out and escorted him back to the studio without telling anyone. During that short span of time I told him that I really wanted to be a composer and that I wanted him to listen to my compositions. He said I should meet him in Bombay.

When I reached Bombay I tried meeting him but it was very difficult and it took months of hard work. There was a TV serial directed by a friend of mine for Doordarshan called Daane Anar Ke. He had asked me to make the title track and I told him I want Gulzar Sa’ab to write the song. I was in touch with Suresh Wadkar and asked him to recommend us and Gulzar Sa’ab agreed. That’s how we did our first song together and he did it for free. The song was Kissa Hai, Kahani Hai, Paheli Hai. He even invited me to the premiere of Lekin. Rekha and I had just gotten married and I still remember how big a moment it was for us to be there. That was also the time I realized that until I left my job at the Recording Studio no one would take me seriously. After I left my job things got even worse. It was a long phase of struggle.

AK: That’s a very big decision that most people can’t take, leaving that sense of security that comes with a job.

VB: Yes, and many people close to you tell you not to do it. I was married, living on rent and it was a very hard time. It’s the same struggle everyone goes through when they’re trying to break into an industry. That’s when Gulzar Sa’ab called me to his house, it was a Sunday, to compose a song that had to be recorded the very next day. The song turned out to be ‘Jungle Jungle Baat Chali Hai Pata Chala Hai’. I sat in front of him, made that song and it was recorded the next day. That song became a hit and I slowly started getting some work. It so happened that I was recording for a film starring Jaya Bachchan (who also happened to be the chairperson of Children Film Society India) at Pan Music Studios. She had also come to the studio and photographs were clicked which were later sent to RB Pandit who asked about me in the pictures. He was surprised to know I had become a composer after being in sales in his company. He then contacted me saying that he was looking to make a movie on Punjab and wanted Gulzar Sa’ab involved. Gulzar Sa’ab after Lekin was not looking to meet anyone. The time for quality cinema had completely gone. 1980s to early 2000, good cinema did not exist unless you made a cheap 25 - 30 lakh budget movie. I somehow arranged the meeting and that’s how Maachis happened and it became our first success.

AK: Where did the seed to turn director come from?

VB I think it happened when I attended a film festival in Bombay in 1994. Before that my only exposure of cinema was either Hollywood commercial hits or Bollywood movies. But when I attended those festivals I realized cinema could have another meaning too. I realized that there was another level of expression altogether. I remember seeing Pulp Fiction and The Three Colours Trilogy – I was fascinated. It made me wonder about what great cinema was and why I hadn’t seen that before. That’s when I decided I would direct. It was ignorance that worked for me. Not knowing fully well who or what Shakespeare was made me take liberty with his plays for my movies. Now after making them I know what and who Shakespeare is and now making a third movie inspired by him, is going to be extremely difficult.

But the first film I wrote was Burf it was going to be produced by Ajay Devgn, everything was on track even the songs were recorded. Now when I look back I realize a pattern in my life – rejection at every major turn. Raju Chacha had flopped and my film was cancelled. For an entire year, I went to every producer with that story. No one refused to hear it but no one took up the project either. Later I had a mutual friend who knew Sai Paranjpe, the then head of CFSI and I was given a break. When the story was passed she suggested that the character in the film be a witch. I made the movie in 52-lakh, Shabana Ji didn’t take any money, and everyone else took R 11,000 as a standard fee. When I submitted the rough cut, my movie was rejected. I knew my film wasn’t that bad. I asked Gulzar Sa’ab to meet me, I showed him my film and he said the movie was good. He advised me to buy my film back. Fortunately because of the credit system it was an amount of 24 lakh. I bought it back and that’s the story behind my first film, Makdee.

AK: Then you made Maqbool, The Blue Umbrella, Omkara and Kaminey. You have a pattern but you also create some thing new every single time because you refuse to adhere to formula. You could make Kaminey 2 and make ten-times the money but you will only make a film that poses a challenge to you. So, how and why do you do this?

VB: Money is just a number. The minimum you should have is the amount you need for your lifestyle. With the grace of god, I don’t think I will ever be deprived of my current lifestyle. I have also seen death very closely in my family. I am very aware that any moment death could come, so I don’t want to do things purely for money. I want to make films that I want to make. I tried doing ad-films in the past. But when I was on set and the ad agency people were discussing the product or the model’s hair for hours, you know how I spent my time, I calculated how many notes I would get if my 10 lakh fee would be given in five rupee notes. No matter what I did there was just no creative satisfaction. During projects like that I realized unless I’m enjoying my work, I couldn’t do it. It’s not that I don’t want to make money or be commercially appreciated, but my work has to excite me otherwise I am not ready to do it.

AK: You have now made a space for yourself where you can do a lot. But my argument has often been that your films should be pitched internationally. Don’t you want to take your films to another audience?

VB: There is a reason behind why I don’t take my films overseas or to festivals. Maqbool was appreciated in Toronto Film Festival and later went to Berlin and other festivals too. But the film wasn’t released internationally. Deepa Mehta also got up in the audience and said she was proud to be an Indian after watching this film, but I felt Maqbool still didn’t get what it deserved there. When the selection committee saw Omkara for the Toronto Film Festival, Cameron Bailey wrote me a two-page email telling me how bad Omkara was and how disappointed he was as a friend and festival coordinator. I moved on, the film was released and appreciated. When the Toronto list was released it included Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna and Kabul Express, I accepted that too. One year later when we did Blood Brothers, the short film on HIV/AIDS, I was invited and I went back. I met a businessman at a party and over a few drinks we became friends. He then said ‘I wish we had met last year then Omkara would have been screened’. I asked him what he meant and he explained that he was the one who picked the Indian movies, and he picked films made by people he had interacted with. I felt so stupid that I felt bad about their comments about my movie. Since then, festivals don’t exist for me and I refuse to be a part of it. I decided I would only make films for my country and its people. It could be perceived as arrogance but it’s not because I’m just not looking for their appreciation.

AK: I feel festivals do have different type of politics and business. But I still feel your movies need to be seen outside of the country too. You have produced No Smoking and Ishqiya. What are your future plans?

VB: After No Smoking my perspective has changed as a producer. I made that film for you. If someone asks me about directors in India today – Mani Ratnam, Dibakar Banerjee and you are the only three who excite me. You are able to tickle me and even make me jealous! You were in a very emotional patch during No Smoking and you were just not able to make that film. Subjects like that really excite me and when it came to making that film, I didn’t want to be a part of the production but I wanted you to make that film. The state of that film impacted both you and me so badly. For Ishqiya we had signed Preity Zinta and we wanted to sign on Irrfan Khan. Preity was the first to back out and a few months later Irrfan said he wouldn’t be able to do it because it was a female oriented film and he had given his dates away, since, No Smoking had flopped. He didn’t think I was capable of making a hit after that. That was it for me, mere andar khundhak thi, I had to prove and make Ishqiya work as a producer. It’s not necessary that every film must work. But since then I swore that I would not produce a film in which I wasn’t a writer because I can’t creatively blame anyone else then. I do not leave room for excuses now. I want to make films, but kissi ka bhala karne ke liye film nahi banani hai. So, until and unless I am inspired enough by someone else’s idea that I want to help write and see it on the screen, I will not produce it. But I still have my own hunger to satisfy and my own films to make.

This conversation initially appeared in our Film Issue 2010 and we are revisiting it as a part of our Celebrating 15 Years of Platform series.