Don’t Interrupt While We Dance, directed by Anureet Watta and co-produced by Siddhartha Bedi, is a film about a group of queer friends on the cusp of mundanity and exhilarating imagination, where being queer is not a plot point or a conflict but a way of seeing, and where cinema becomes about the allocation of time between suffering and hope. We spoke with the director, Anureet Watta, about the idea of queer joy, cinema as language and the importance of unserious desires.

The word ‘queer joy’ has been closely associated with your film; tell us what queer joy means to you.

Queer joy visited me when I started living in a queer household - our days burdened by identity, but lessened by the leisure of simply being without repercussions. My goal to make films is much like that of a well-made cake. I want to relish films with those I love, and I would like for them to always eat well. As a filmmaker, queer joy in cinema becomes about the allocation of time between suffering and hope, always in a battle with the run time. A large part of cinema (notoriously through the gaze of cis-het men) centers queerness as a conflict, as a mishap, in an otherwise ‘normal’ life - this victimhood takes center stage in these films. In this allocation of time, the entirety of our lives becomes a practice of explaining and making up for the misadventure of being queer. But being queer is not a plot point or a conflict or an inciting incident, it is a way of seeing; of looking, and being looked at, it is how we navigate the world, disrupting it and allowing it to disrupt us. Being queer, as many have said before me, ‘saved my life’, because it ripped apart blueprints of convention and taped itself to new meanings, and in that we are not simply subjects of the world, we are also creators of it.

In this pursuit, I want to make queer stories that allow my people the space to triumph, to be happy, to be bitchy, and to be here for the fun and wonderment of life itself without having to attach greater meaning. To make space for vivid imaginations and delirious laughter. And queer joy cannot exist until there is Palestinian joy, until all political prisoners are free until we as a country are truly anti-caste. These joys cannot be fleeting; they are interwoven in a mesh of experiences. All of these existences must be liberated and then dazzling.

Is there a gap in queer representation in Indian films today? What kind of storytelling do you hope to foster in the Indian filmmaking landscape through Don’t Interrupt While We Dance?

I think I am keen on working with people for whom these stories are not just little thought experiments that can be let go once the film is over. Who are the producers, who are the platforms, who are the creators on and off camera, these are questions valid to ask today in the light of the genocide, the rising extremist violence in our country, and the token inclusivity offered to us. To make art politically would also be to question the ‘capitalist’ concept of profitability, and ownership. The gap in queer representation can simply be explained by noticing the skewed numbers behind and in front of the camera. And that ‘queer cinema’ is still a category or a genre. I aspire for queer films to just be films, to be about queer people but also about something else, where queerness is not a theorem to be solved through a film, but a true axiom, and then the film gets to be about the entirety of the spectacular universe, be it pirates or ugly romances or conniving robbers or lonely children or reincarnated lovers….

Don’t Interrupt While We Dance was written in December 2022 and I first shared it with the world, essentially my friends, on a Christmas afternoon. We had a party, and before the real party started, a few friends gathered around as we read the script aloud, for the very first time. It was surreal

reading a film about a group of friends having a party, while sitting in a room full of my friends, about to do the same. It remains one of my fondest memories. Right after the party, the next morning, we faced threats and eviction warnings from neighbors and landlords - ‘Pata nahi kis kis tarah ke log aate hai.’. We were the much-defamed and queer household in the locality. It was absurd for art to precede life in that manner, but these were truths that were unsurprising to us. Until that point, the film was titled something else, something to do with spring (a strange phase of my life where I was obsessed with ?lms having seasonal names, much like Oranges in the Winter Sun). Musing on it with my friend Pia, together we came up with a list of ‘Don’t Interrupt While We _____’, listing all unhurried verbs we knew, and Dance seemed the most frivolous and hence it fits best. I wrote the ending of the film with the new title in mind. Over time, I believe this film could not have any other name, it is about an interruption and it is about unserious desires such as dancing or yapping. The ?lm is about a group of queer friends, who are on the cusp of mundanity and scintillating imaginations, and they could always be that way, until the world barges in, asking them the shape of their hearts and the names of their desires.

Making the film was just that, we made friends along the way and we made the film with friends. When we rehearsed to dance, there was no cast or crew, the story we gathered to tell, was something we had all lived and so there was an infectious laughter of being in a room full of queer creatives, trying to make something that may outlive us.

What is your relationship with film? Why is it your chosen medium of creativity?

Film is not the only medium I dabble in - I arrived here through prose and poetry, and even now much of my time spent creating is on the cusp of multiple mediums, always bargaining what fits best where. I feel the beauty of each art form is that it brings to the table some core textures that are untranslatable to the other. While the contexts in which all my works operate harbor familiarity, the emotional lexicons they speak in are vastly different - poetry is an individual exercise and offers a facelessness, so when a metaphor breaks, it opens room for the reader to situate themselves in it in first person. On the other hand, I write novels or essays because I enjoy the deliciousness of language and the temperament of words to lead to new meanings without much hesitation - put 'soot' and a 'lash line' together and now you have the story of a lover in a burning city. Cinema, on the other hand, is a creation of multiplicity, moving from frame to frame and sound to sound. I love the creation of the story through the unspeakable, outside the boundaries of language.

While I have formally studied none of these art forms, I see an idea always emerge at the confluence of all these mediums, and later I weigh what would be best suited for this story to explode. I am very keen on queering processes as much as the final product of the film. Once you step out of the molds of expectations and rules, conventions seem to hurl out of the window and what is left is a vivid tapestry with a manifesto built out of aspiration. This I believe is the most permanent part of my process - to always seek and situate in the transient.

I am currently writing a novel, based on a screenplay I wrote for the Writer’s Ink Screenwriting Lab, titled ‘Ruli Hui Nazmein’. While developing this script during the course of 4 months for the lab, while I found fruition in the story as a cinematic medium, I found a lot of it was untranslatable for the screen. Hence, I now approach this to explore the excess that a novel offers. It is a magical realist story set in the 1980s in Delhi. Centering two protagonists, Laila and Tara, students in a women’s college; it follows their queer experiences and desires, their love in a time when queerness was almost absent from the urban Indian lexicon against a background of the political turmoil following Indira Gandhi’s emergency and assassination, and a rising women’s movement.

Further, I was recently a part of the QueerFrames Screenwriting Lab and had the opportunity to present my project at the European Film Market in Berlinale 2025. It is a dark comedic thriller set in a world with deeply flawed and ruthless queer characters operating with a high tolerance for violence, called Muskuraiye Aap Lucknow Mein Hai. It follows two lesbian pickpockets, partners in crime and desire, dream of escaping the city of Lucknow, and the tribulations of marriage fated for them. As one betrays the other in a bloody heist, the other scraps the city for revenge, propelling a cycle of violence that grows larger with each move. It is a first-of-its-kind Indian thriller film centering morally ambiguous queer and female characters with an affinity to violence. The characters take the very parts of them that have been branded as subservient in the world, to be flipped to make the world subservient. At the core of it, ‘Be Gay Do Crime’. I hope to make this feature film soon!

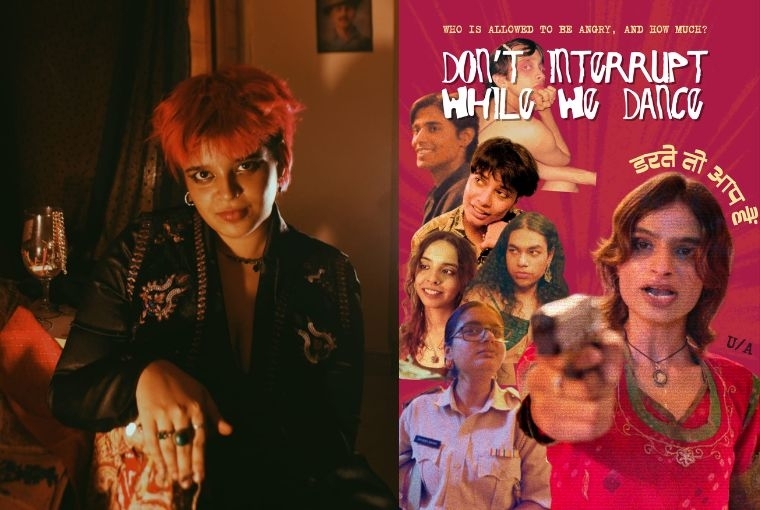

L: Director, Anureet Watta, Photo by Sarthak Chauhan

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 22-8-2025