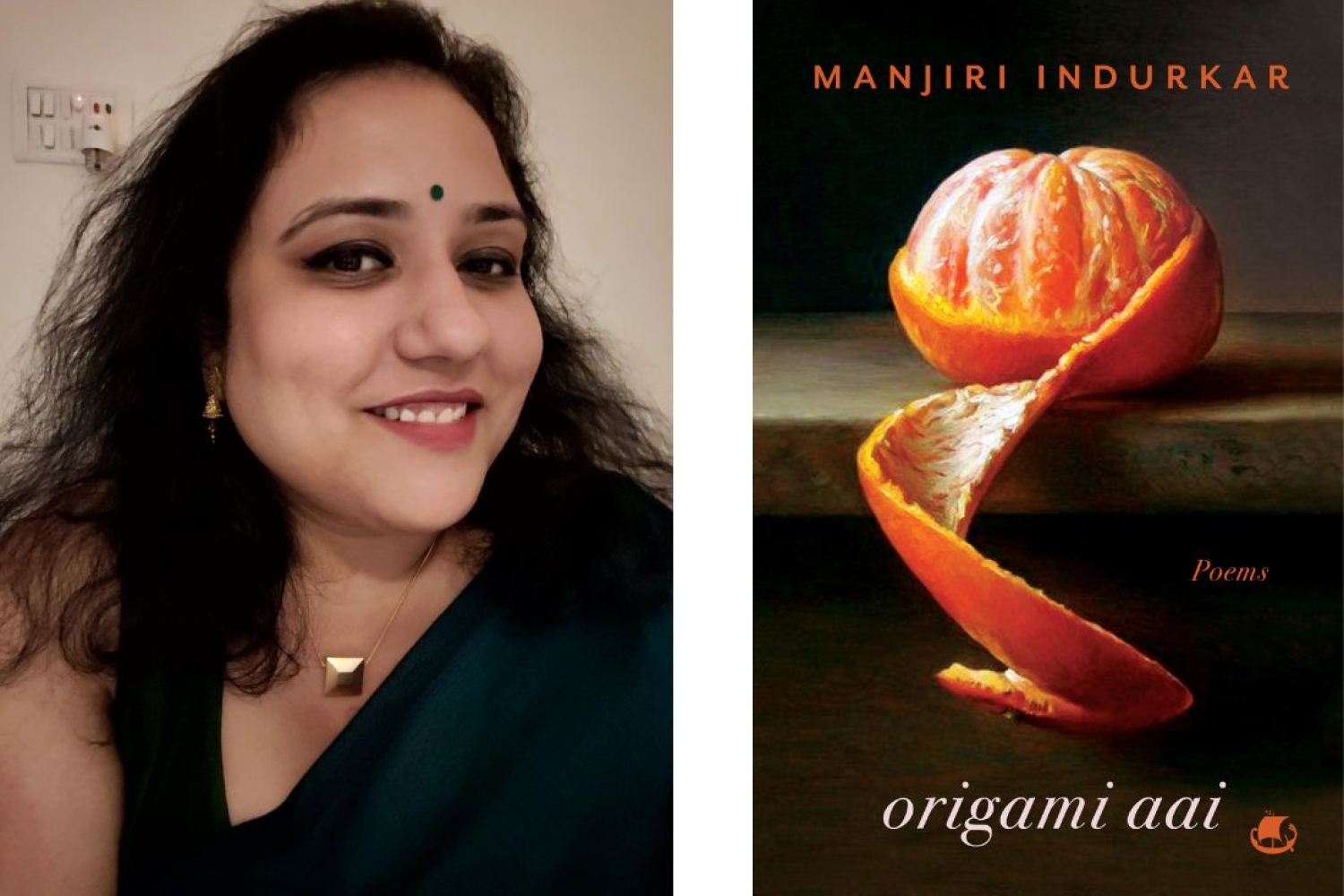

Manjiri Indurkar's immensely personal poetry collection, Origami Aai, allows us to enter into a space that deals with the horror, politics and trauma attached to the complexities of families, all with a touch of humour, Hindi cinema and pop culture. Her ability to juxtapose the heavy and the light makes her collection a complete deep exploration of her inner self. The poems in the collection merge with the form of prose, revealing much of Indurkar's experiences in the form of prose yet hiding them in the poetic language. In this poetic language, she evolves her relationship with nature, the non-human, other writers, love and language itself—but most importantly with her Aai. She talks to us about the form of prose poetry, her writing process and how her family has shaped her and her poetry collection.

Your poetry in the book often merges with the form of prose. Tell us about the form of prose poetry and why you chose it.

Form is as much a conscious choice as it is about the poem writing itself. I think often it is my instinct that makes these choices. This isn’t to say there weren’t influences. Charles Simic’s prose poems in The World Doesn’t End were an early inspiration for me. While reading Nabokov’s prose, I was struck by its lyricism and the poetry in it. I don’t think of myself as a poet who experiments much with form. I think my experiments are more in language and references, and the use of the everyday magic and horrors. But some poems tell certain kinds of stories. These stories feel heavy and relentless in their pursuits of flowing out into the world. In this, it’s the prose form that provides a break-free space. Without any gaps and even the permission to breathe. I especially think this form works very well “horror” which is one of the poetic tropes I am deeply interested in.

Tell us about why you have titled the book as Origami Aai.

The title, at first, was going to be Origami Birds, based on the poem in the collection because I felt it’s the one poem that encapsulates the love, affection, anxiety, stress, terror, and general preoccupations in life. It was my friend Divya Nadkarni who suggested the name Origami Aai. This collection is heavily based on poems about mothers—fragile, crude, imperfect, cruel, caring, everything. It is my obsession with what is probably a fear every person goes through, but in my case, it has been present since my childhood—losing my parent. And because it is my mother whom I have seen sick a lot, it is her I worry about more; it is her I want to desperately hold on to, and so, keep her with me. But is it the fear for her benefit or mine? An origami anything isn’t living, sentient. But it’s present, tactile. Hence, Origami Aai, who can always be with me, always. It’s a representation of my fear and anxieties and my love, which often can be cruel and caring simultaneously.

What is your writing process?

I wish there was one. I have often written like I am under a spell. It’s the idea of vomiting all that is inside out on the paper or Word doc or Google docs, and then working with the poem staring back at me. Editing it is a process that has taken me years. I have failed at Hemmingway’s ‘kill your darlings’, at least until the darlings were ready to be killed. It is a strange thing, but if I wrote a poem today, depending on how I am feeling about it, I may or may not be able to touch it. But, maybe if I return to it tomorrow, next month or next year, I will be able to edit it out. The poem 'Lonely Cities' was edited over 3 years. The poem ‘The two-thread consistency of goad amba’ over 5 years. It’s just how this has worked for me.

The narrator of these poems is a child through which you delve into subjects like death, how do you think a child's voice helped you in exploring such topics?

It is my inner child who is often finding avenues of escaping out and speaking her mind, and living the life she wasn’t allowed to when she existed. My life has been influenced heavily by my childhood experiences. I wouldn’t say they define me, but they do sit heavy on my shoulders. After the first book that came out, It’s All in Your Head, M and this poetry collection, the inner child has finally done a lot of talking, and maybe, even is, all talked about. This is why you can notice a shift in some poems, and whatever I now write is different from whatever I was writing all these years. Maybe the voice has grown and matured, which isn’t necessarily a good thing because the inner child is all talked out in my prose, poems, and therapy.

You explore the interaction of human beings with non-humans at many points in the book. Tell us more about this juxtaposition.

My grandmother was a peculiar woman. She was flawed in many ways and was sometimes unkind to me, but she was a terrific storyteller. She is the one I’d give credit for this association with the supernatural. Growing up, she narrated horror stories to me, which in her world were real events she wanted to protect me from. So, these stories worked as forewarnings. They terrified me to no end, but I was also very enamoured by them. I was an imaginative child who would build stories in her head all the time, so these stories of my grandmother stayed and grew with me. I would narrate them to my childhood friends too, because their grandmother wasn’t telling them any stories. In some sense, I ended up becoming a storyteller before I ever knew I wanted to be one. And I drew associations of people and their things, as props for the stories I told. This juxtaposition, as you call it, is nothing else but a means of telling a good story.

Why does your family become a major part of your work?

One, I think, is the simple rule of writing what you know. The other is that I am deeply, deeply interested in the politics of domesticity. I want to understand what goes inside a house, inside a kitchen, the bedroom, and the spaces that women predominantly occupy and run. And my family offers me a first-hand view when it comes to exploring the themes of domesticity. A favourite poet of mine, who is also a dear friend, Nandini Dhar, has worked on similar themes in her poetry collection, Historians of Redundant Moments. Looking at the mother, I am not interested in the guardian angel who can do no wrong or is next to god tropes. I have no interest in valorising any mother, especially my own. I want mothers to be complex, complete human beings. And that is the mother I write about, because, for me, there hardly is any other subject half as fascinating as the women who raise us.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 16.11.2023