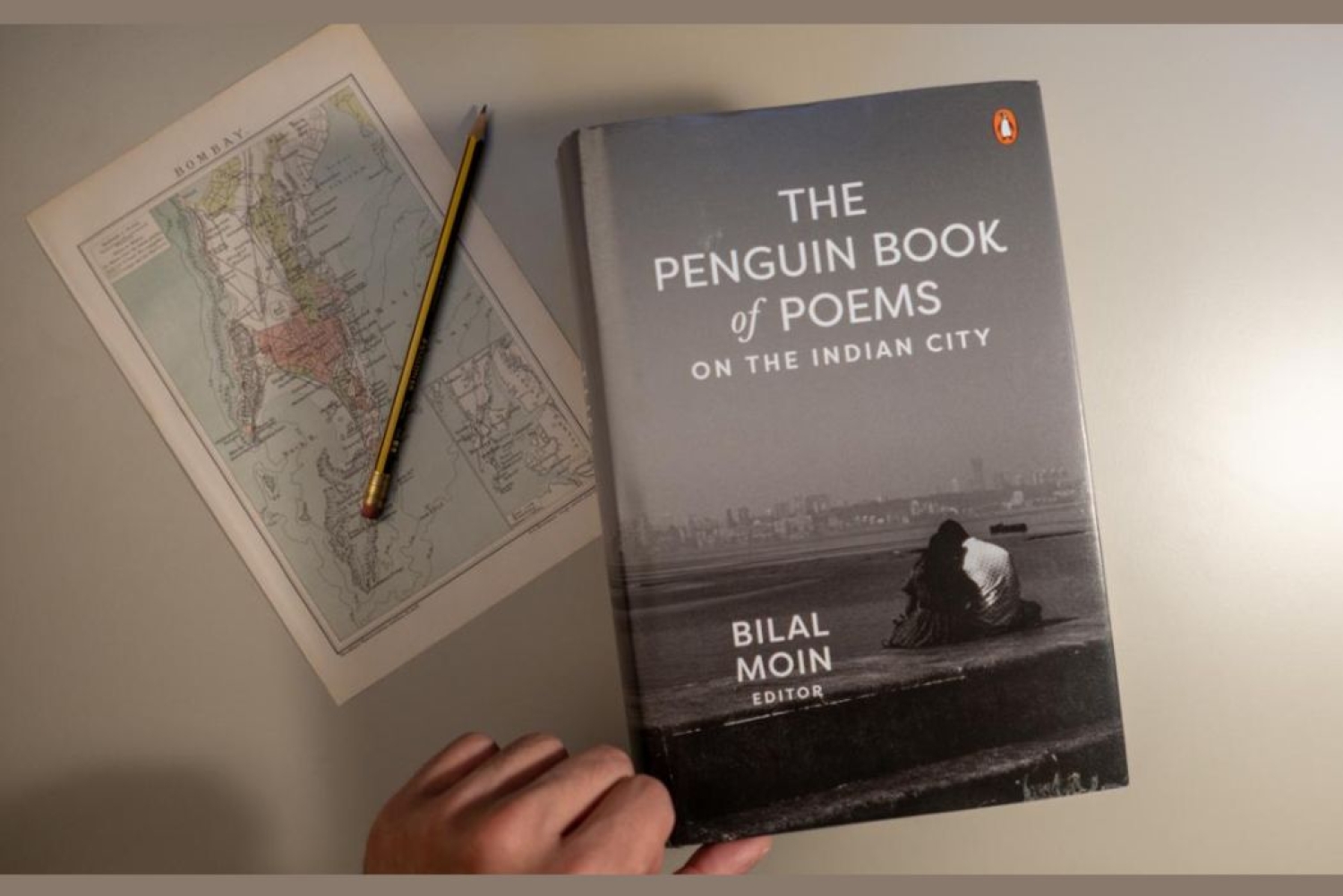

If a city could speak, what stories would it tell? Bilal Moin’s new anthology, The Penguin Book of Poems on the Indian City, might have some answers. This vibrant collection curates the voices of poets across a millennium and a half, all singing about the bustling, chaotic, and enchanting life of Indian cities. It’s a project born from an unexpected place: the wistful nostalgia of a homesick student.

Moin recalls how the idea first took root when he was an undergraduate in the United States, feeling thousands of miles away from home. 'It was in many ways born out of nostalgia, because I was… quite homesick,' he admits. Born and raised in Mumbai, Moin found himself poring over verse about his beloved Bombay and other Indian cities to feel closer to home. As he kept gathering poems, about Bombay, Delhi, Kolkata, and beyond, he realized he had stumbled onto something special.

'I was just surprised that no one had put together an anthology [of poems on Indian cities]. And [my professor’s] advice was, "if no one has done it, it’s probably worth doing,"' Moin says, remembering the conversation that spurred him to pursue the idea in earnest. Soon enough, Penguin Random House India was on board, and Moin was officially an editor, assembling a literary map of India’s urban landscapes.

By Day an Economist, By Night an Editor

It’s an unlikely moonlighting gig for someone like Moin, who by day is an economics researcher and MPhil candidate at Oxford University. The anthology, published in May 2025, is an opus nearly 1,100 pages long, gathering 375 poems set in 37 cities. It spans works written in English alongside translations from almost twenty Indian languages. The scope is staggering: from classical verses by sages like Valmiki and mystic poets of the Bhakti and Sufi traditions, to modern icons like Nissim Ezekiel and Gulzar, all the way to young poets born in the 21st century.

How did Moin decide what cut to make for such an expansive project? He approached the task with two simple rules. 'Number one, the poetry should be on the theme… a poem on an Indian city. And number two, the poem should be good, either in translation or in English,' he explains. These criteria sound straightforward, but they opened the door to a remarkably diverse set of voices. By not feeling obligated to include a poem merely because its author was famous, Moin gave space to many writers who might otherwise be overlooked. 'It allowed me to represent a lot of unrepresented voices in the field,' he says. Indeed, flipping through the anthology is like walking through a bustling bazaar of voices: you’ll encounter revered classic poets alongside emerging talents whose work had previously appeared only on Instagram. The youngest poet featured was born in 2003, just as the oldest verses date back over a thousand years.

With around 20 languages represented, the book strives to be as multilingual as urban India itself. In fact, Moin initially gathered even more, but practical limits of length forced him to trim down the selection. “The one thing I wish we could have done was just get even more languages,” he reflects, acknowledging that no single volume can capture the full linguistic tapestry of the subcontinent.

The Many Faces of the City

Every poet approaches the city differently, often depending on their relationship with it. Moin likes to think of these perspectives in three archetypes: the traveller, the lifelong resident, and the exile.'On one extent, there is the traveller who is in a city very briefly and experiences it from a tourist’s eyes and then leaves,' he says. These poems capture the fresh astonishment of first impressions—like a newcomer marvelling at Varanasi’s ghats or the India Gate lit up at night. Then there is 'the lifelong citizen of the city… people who take great pride in what the city means to them,' Moin explains. Finally, perhaps the most poignant category: the exiled poet. 'These are people who’ve emigrated or have left… or the cities they grew up in just no longer exist because time has destroyed them or they’ve undergone a lot of civil violence, so they no longer feel like the city is theirs,' Moin says. Exile poems carry a heavy nostalgia, a longing tinged with loss. Together, these different gazes make the anthology richer.

Hidden Gems and Personal Favourites

With 375 poems in the collection, it’s hard for Moin to choose favourites – asking him to pick one is 'like you’re asking me to pick a favorite child,' he jokes. But there are a few pieces that delight him as a reader. He lights up talking about a Hindi poem called Breaking Stones, written by Nirala about a labourer in Allahabad and translated by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra. The poem describes a fleeting encounter: a woman breaking stones by the roadside, and the silent conversation the poet imagines with her as he observes her hard at work. It’s a simple vignette of city life, yet full of empathy and imagination. Moin is also fascinated by discoveries like From the Temple of Justice, a century-old sonnet about the Bombay High Court penned by a now-obscure Parsi lawyer, Feroz Dastur. 'We know nothing about his life… he was a barrister who wrote poetry on occasion. But this one piece of poetry he’s written has survived for so long, and has endured,' Moin says, marvelling at how a single poem can outlive its author’s fame. In Dastur’s verses, Bombay of the 1920s comes alive with litigants of every community—Khojas, Marwaris, Kutchi Memons—scurrying through the halls of justice. For Moin, unearthing such a gem was like time travel, a rare peek into the social fabric of a bygone city.

The anthology also offers up celebrated voices in a new light. Take Mirza Ghalib, the legendary 19th-century poet known for Urdu ghazals. Few remember that Ghalib wrote in Persian too. In The Penguin Book of Poems on the Indian City, one finds Ghalib’s glowing tribute to Benaras (Varanasi) from his Persian work Temple Lamp, rendered into lilting English.

Reflections and Looking Forward

Bringing this anthology to life has been an educational journey for Moin himself. One thing he learned is that rumours of poetry’s demise are greatly exaggerated. 'It’s very easy to… complain that good writing is dead, and that there’s no good writing left. I don’t feel that’s true. There are a lot of very good writers out there,' he says with conviction. Many of them might not have mainstream publishing deals or big reputations yet, but their work is out there in literary journals, online platforms, or regional publications, waiting to be discovered. Another realization Moin had was humility in the face of India’s literary ocean. 'No matter how well you think you know India, or you know Indian writing, there’s just so much more to learn,' he reflects. Even after compiling 375 poems, he knows he’s only scratched the surface.

Words Harita Odedara

30.06.2025