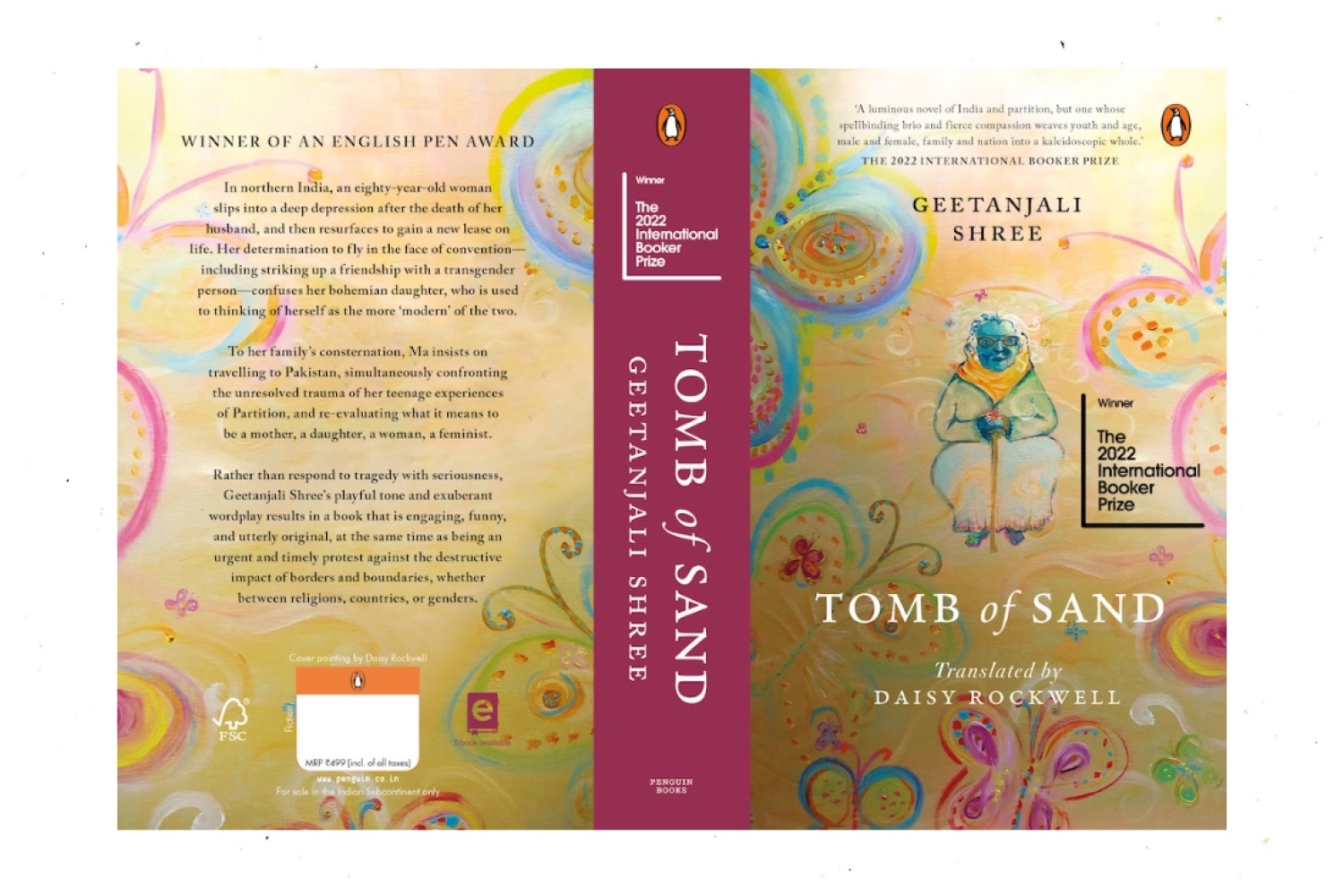

For Indian literature, history was made earlier this year. Tomb of Sand, Geetanjali Shree’s Hindi-language novel, was awarded the International Booker Prize. The English translation by Daisy Rockwell led to the historical moment where, for the very first time, a novel translated from an Indian language was bestowed one of the highest literary honours for translated literature. The recognition was immense, and rightly deserved. Geetanjali Shree’s book is a marvel, both massive in its scope and nuanced in its exploration of the lives women lead in our country.

Dairy Rockwell tells us more about the book and its translation below:

How were you led towards the world of Hindi literature and translation?

I started learning Hindi in college at the University of Chicago, just for fun, with no background in the language or culture. I was quickly hooked, and went on to study Hindi literature in graduate school. My Hindi professor, Colin P Masica, recommended I try my hand at translation, and I also had the good fortune to take a translation seminar with AK Ramanujan, who was also a professor in my department.

Congratulations on winning the International Booker Prize! Could you take me through your creative process behind translating Tomb of Sand?

For every book I translate, I first write out a rough draft by hand, then type it into the computer, then begin the process of bringing it into English. Most translators go through many drafts. Tomb of Sand was particularly difficult because I had many many questions I needed to ask the author, often as many as ten a page. These were questions that only she could answer, and sometimes even she was not sure how to explain why she said something a certain way. So this turned into a lengthy collaboration over email, with her reading the full draft at a certain point and commenting on it in detail.

Your views on a translator’s relationship with the author.

Most of the books I have translated have been by authors who are no longer with us. So working with Geetanjali was a very different experience! I think the relationship is highly varied. We had to work very closely together so we have ended up being quite close. Other translators barely interact with their authors. It really depends on the circumstances.

With so many nuances and much that is said between the lines, how do you make sure a story is found and not lost in translation?

Some of it is good old fashioned hard work, and some of it is instinct and creativity. Translation is made up of both of these things. Some things may get lost along the way, but many things are found as well.

What is the greatest challenge of the art of translation?

The greatest challenge is when you have translated something accurately, but then you stand back and realise that it sounds completely wrong in English. Then you have to ponder what the author meant exactly, free of language, and try to rewrite it so that the original intention is clear.

How have you been coping with the pandemic? Has it affected you as a translator in any way?

I have realised thanks to the pandemic that I translate better outside of my home, in public spaces, like libraries and cafes. I was deprived of that for quite a while and it was hard for me to work. I have a study in my home, but for some reason it is harder for me to focus in there at times.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

So many things! I’m finishing up a novel by Usha Priyamvada, Won’t you Stay, Radhika?, and I’m also close to completing a first draft of Channa, Krishna Sobti’s first novel that was first published shortly before her death. I recently completed a prose poem by Urdu poet Azra Abbas, called Sleep Journeys, and I’ve been working on some of Geetanjali’s short stories. And then I am also hoping to soon begin work on an Urdu novel called Nagari Nagari Phirta Musafir, by Nisar Aziz Butt, which I like to tell people is like Magic Mountain meets Middlemarch in the Northwest Frontier Provinces of Pakistan.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 26-09-2022