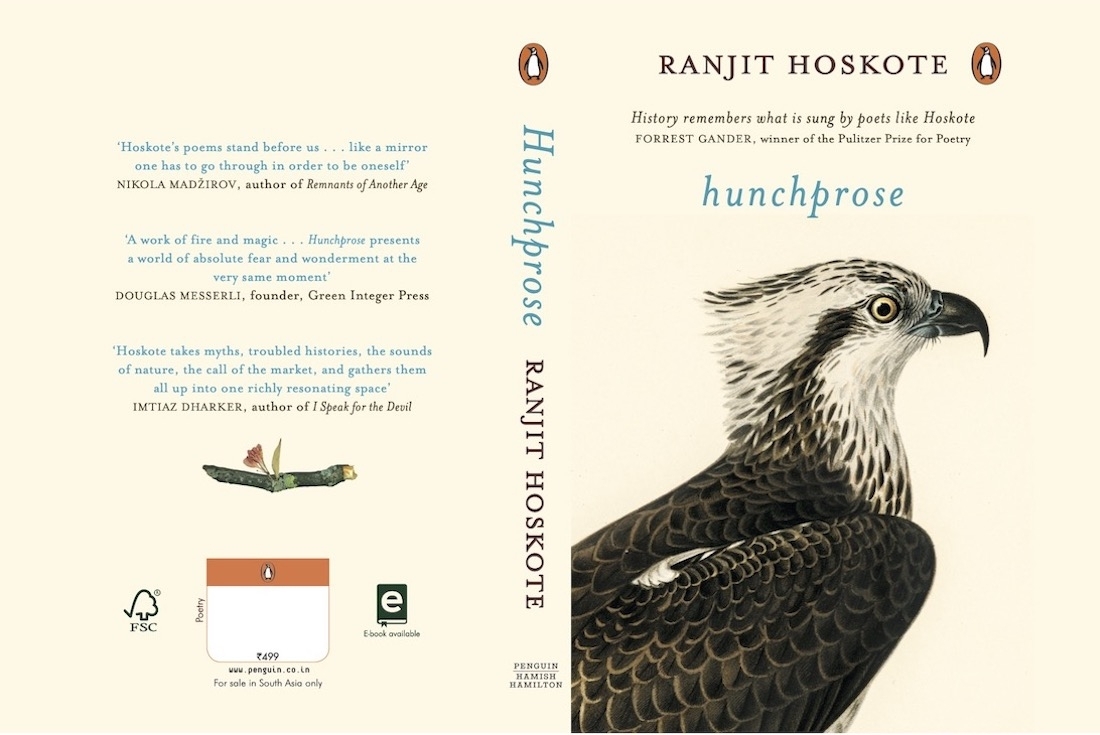

From the epic of the classical age to the free verse of today, poetic creation has been an indispensable facet of human existence. As human civilisation has evolved over the centuries, so has poetic form and its concerns. In our contemporary reality, many socio-cultural and ecological issues have pervaded our being, and it is hence a necessity that some of these issues be addressed by the poetic brilliance of Ranjit Hoskote. In Hunchprose, the poet redirects us towards our milieu with urgency. As humanity slowly moves towards apathy and amnesia regarding anxieties of belonging to our world, the book breaks this singular movement, to celebrate the plurality of both our world and ourselves. With each poem comes a new experiment in the linguistic form of poetry. Many voices are at play, many quandaries are voiced, and many discoveries await. Hunchprose is a book that deserves attention by everyone. It is a book that warns, and a book that redeems.

We connected with Ranjit Hoskote to know more about his poesy and the book.

After all these years, how would you define your relationship with poetry?

Poetry has grown ever more central to me, as a way of approaching and bearing witness to the world; as a way of shaping my contribution to this kaleidoscopic world of shifts, transitions, surprises and discoveries. The language and music of poetry, the pauses and cadences of poetry — these are the materials from which I try to pave thresholds and build bridges.

What inspired Hunchprose?

Hunchprose emerged from an increasing sense of urgency, for me, on multiple fronts. As a poet, how best could I map my location in a public sphere eclipsed by loudness and speed, how best could I to make a claim on utterance? As a citizen, I have been preoccupied by the ecological catastrophe that we are living through, which we as a species have brought upon ourselves and our fellow denizens of this planet. As a citizen, too, I have confronted the narrowing of the space for free and dissenting expression and, alongside this, the brutal and relentless polarization of society.

Through the period that I wrote Hunchprose, I had the sense of standing at the edge — on a coast lashed by unpredictable tides, on a precipice, poised between endings and beginnings.

Could you give us an insight into your creative process behind creating the book? Since some poems were earlier published elsewhere, how did you curate them for this collection?

I structured the book as an echoic flow, a stream with its internal harmonies and connections, with the thematic emphasis shifting every four or five poems or so. Rather like how a language shifts register, vocabulary, tonality every few miles in any region of India. To me, Hunchprose is a continuous and polyphonic narrative, told in many voices, by many personae — among them, the weatherman in Mehrauli, the epic poet at the harbour, the emancipated slave and expert guide Sidi Mubarak Bombay, the trapeze artist and the anthropologist, a Neolithic artist and the long-ago governor of a Mediterranean city.

The poems range in form, tonality and affect — some are aphoristic, others are fables, yet others are cautionary tales; some expand to embrace histories of colonial exploitation and imperial expansion, others are prayers or hymns. At the core of all these departures is the human subject, vulnerable yet crafting a path for herself or himself through hostile landscapes, survivor, explorer, hostage, and pilgrim all at once. The poems from the book that have appeared in journals or anthologies were drawn from this flow.

There are many contemporary socio-political concerns addressed in the book. In terms of theme, was there a singular driving force behind the making of the book?

The key themes of Hunchprose are home and the journey, the experience of displacement and the attempt to shape a space of belonging, the seesaw between power and freedom, the asymmetry of masters and slaves, the possibility of releasing oneself with empathy towards other species, the climate crisis, the afterlife of empire as experienced in degraded cultures and topographies and the attrition of linguistic diversity, the evocation of destroyed civilisations as an image of the future that is already upon us.

The driving impulse that unifies Hunchprose is my questioning of the dogma that we, humankind, are the sovereign species on Earth, and that the planet exists to serve our insatiable greed for resources and satisfaction. Once we question this dogma, we can begin to look for resources of hope and redemption, ways of healing and mending ourselves and our environment.

Linguistically, this collection of poems is very intriguing and experimental in nature. Some poems have absolutely no use of punctuations. What was your intention behind this play with structure of language in the poems?

My experiments with form in Hunchprose — the near-absence of punctuation, the syntactical looping and slippage, the shaping of poems through a mise-en-page that invites the reader to trace the patterns by which the poem can be read — come from a desire to bring into English the linguistic possibilities of Sanskrit and Urdu. This springs from my long-term commitments as a translator. I have been working on the poetry of Bhartrihari, Amaru and Bilhana — to be published in the near future — and on the ghazals of Mir and Ghalib. My apprenticeship to Urdu has been particularly formative of the experiments in Hunchprose. I would like to bring into my language some of the shimmering, diaphanous effects that Urdu’s subtleties and multiple legibilities permit.

My attempt has also been to bring more emphatically into poetry my experience as a listener of music, especially of Hindustani music, with its syncopations, its dynamic of laya and taal, flow and beat. The poetic forms in Hunchprose are ways of celebrating the plasticity of line, the movement of the poem in space, and the diverse registers of voice.

What do you hope the readers take away from this book?

I hope that readers will take away from this book a sense of epiphanic pleasure — a pleasure compounded from enigma, beauty, disquiet, and discovery.

Lastly, how have you been coping with the pandemic and what are you working on next?

The pandemic announced itself very clearly as a time of anxiety and disorientation, and I made practical preparations to deal with this, especially to protect and insulate my aged father from the threat of the virus. For myself, I decided early on to treat the pandemic and lockdown as an extended writing residency, and to continue with my ongoing projects while opening myself up to dimensions of experience that tend to be marginalized by the momentum of life normally. It’s been a time of return — to friends and comrades, across sometimes oceanic distances; to the openness of sky, the proximity of birds and animals, the presence of the ocean.

As to what I’m working on next — ideally, I wish I could finish one thing and begin another, but that’s not how my cycle works! So I’m working on a non-fiction book, provisionally titled Lost and Found Histories, while also refining my translation of Mir Taqi Mir. I’ve been working on a curated exhibition, Patterns of Intensity, which opens at Art Alive, Delhi, in April, and on a large-scale exhibition of Zarina Hashmi’s work, to open at the Mathaf Museum of Modern Art, Doha, in two years’ time. And I’ve been working on my next collection of poems.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 02-04-2021

Portrait by Nancy Adajania-Utrecht