“Out of the eleven filmmakers featured in the book, eight are mothers. What’s more, all of them have continued to make films after becoming a parent. At times, I was surprised to see the filmmakers I admired for their powerful works ensconced in family life, talking at length about the mundane details of being a parent. That shattered the binary in my own mind - of the artist and the mother. It also dismantles the myth of the elusive male artistic genius who withdraws from the world in order to create art.”

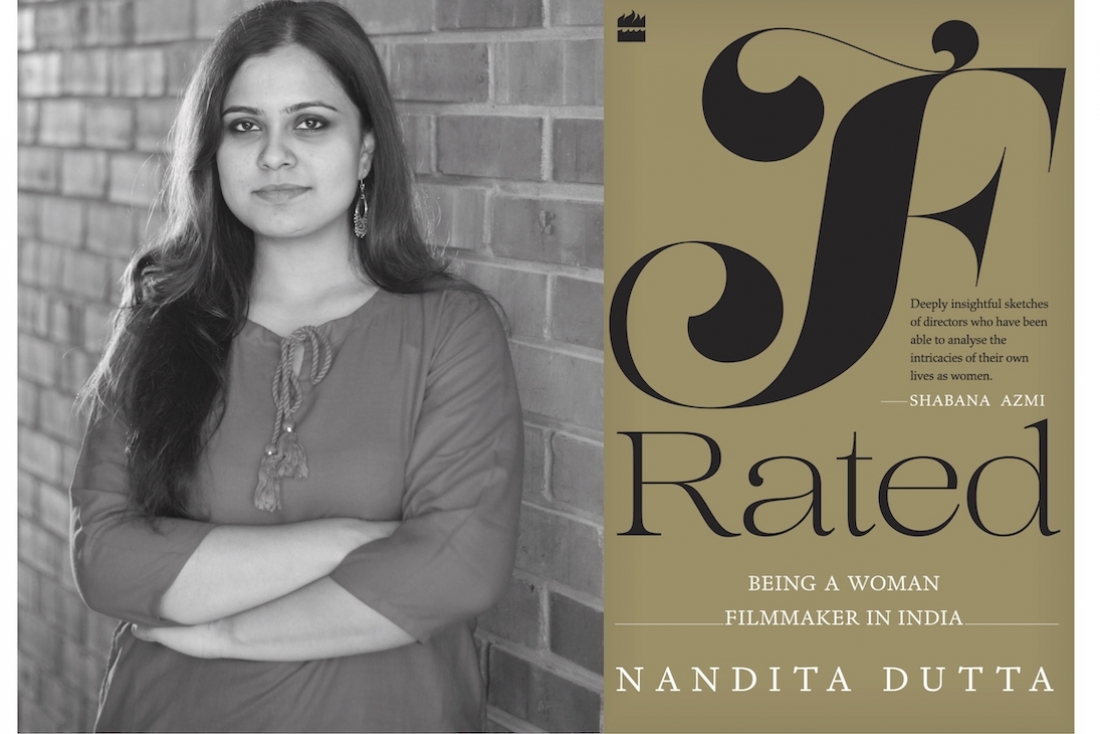

Nandita Dutta works at the Centre For Studies in Gender and Sexuality at Ashoka University and after completing an MA in Gender Studies from SOAS, University of London, she decided to combine her passion for both cinema and academics in her debut book.

Through F-Rated, Dutta brings us the stories of eleven women filmmakers in India: Aparna Sen, Mira Nair, Tanuja Chandra, Farah Khan, Shonali Bose, Reema Kagti, Anjali Menon, Nandita Das, Meghna Gulzar, Kiran Rao and Alankrita Srivastava. She uses the lens of gender in her book, which primarily deals with understanding what it means to be a woman filmmaker in India.

We got in touch to explore her inspiration, challenges and more. Excerpts.

How did you combine both cinema and academics in your research?

Actually, cinema led to academics. When I started writing F-Rated in 2014, I was a film journalist by profession, covering independent cinema in India and the rest of South Asia. But it seemed to me that if I wanted the book to be something more than a journalistic exercise, if I wanted it to tap into the broader debates in the field of gender and feminism, I had to first train myself. Therefore, I decided to pursue an MA in Gender Studies and that is where my academic journey started. Looking back, I could not have made a better decision. Academia gives you the necessary critical and analytical lens to look at a subject, while journalism gives you people skills. What I already had - importantly - is a passion for both gender-based issues and cinema. So, thankfully, everything fell into place for this book.

How did gender studies change the way you look at things?

It teaches you what to look for, and then makes you see things which others may not be able to spot so easily. It gives you important tools to move through the world. To give you a concrete example, I faced some amount of resistance from filmmakers on being called as “women filmmakers” in F-Rated. I think one of the main reasons for that is that they do not think about the fact that we are all gendered subjects. While to me, coming from a Gender Studies background, that is clear as day. In a similar vein, there are a lot of experiences on the set which they didn’t think of as having to do with their gender, while I did.

What inspired F-Rated?

Curiosity and admiration. Curiosity about why there were so few women filmmakers in India, and admiration for the ones who had made it big. I wanted to see if it was possible to explore the gendered dimensions of the film industry through telling the stories of those who have excelled here.

What challenges did you encounter while writing F-Rated?

Challenges are integral to how something like this shapes up, aren’t they? I had two filmmakers withdraw from the book and that bogged me down. Zoya Akhtar, who I greatly admire as a filmmaker, pulled out of the book because she thought it was too focused on gender. Gauri Shinde withdrew because she didn’t like my critique of her films. Those are the two real, external challenges I can think of. Rest was all part and parcel of the process of writing a book.

This book helps you “dismantle the myth of the elusive male artistic genius who withdraws from the world in order to create art.” How did you shatter the binary of the artist and the mother through the course of this book?

This was a big transformation that I went through myself in the process of writing F-Rated. I dove into the book thinking I was going to write about the artist, but I emerged on the other side having written about the mother and realising that the two were inseparable. It just so happens that out of the 11 women in the book, 8 are mothers, and they talked at length about the entanglements of motherhood and creative work. So that I am not misunderstood as being poetic here, I am talking about the practical challenges that motherhood poses, the kind of banal things we find unglamourous to talk about. And I made the decision to talk about it extensively in my book. If we want more women out there, we have to first talk openly about the challenges women face, about the different material realities that women have, and alternative paradigms of being artists and leaders that are not so masculine in nature.

Having interviewed eleven female filmmakers in India, what’s your greatest learning?

That a book like this should not run the risk of homogenising women. They are different, and yet might share certain experiences on account of their gender. Secondly, that there is a lot of bias and sexism out there, and nobody wants to talk about it.

What will you work on next?

On the academic front, I am starting a PhD that will look at how spaces interact with female sexuality. On the creative side, I have been working on something but haven’t mustered the confidence to start talking about it yet.

Text Priyanshi Jain