R: Reema Abbasi, the translator

R: Reema Abbasi, the translator

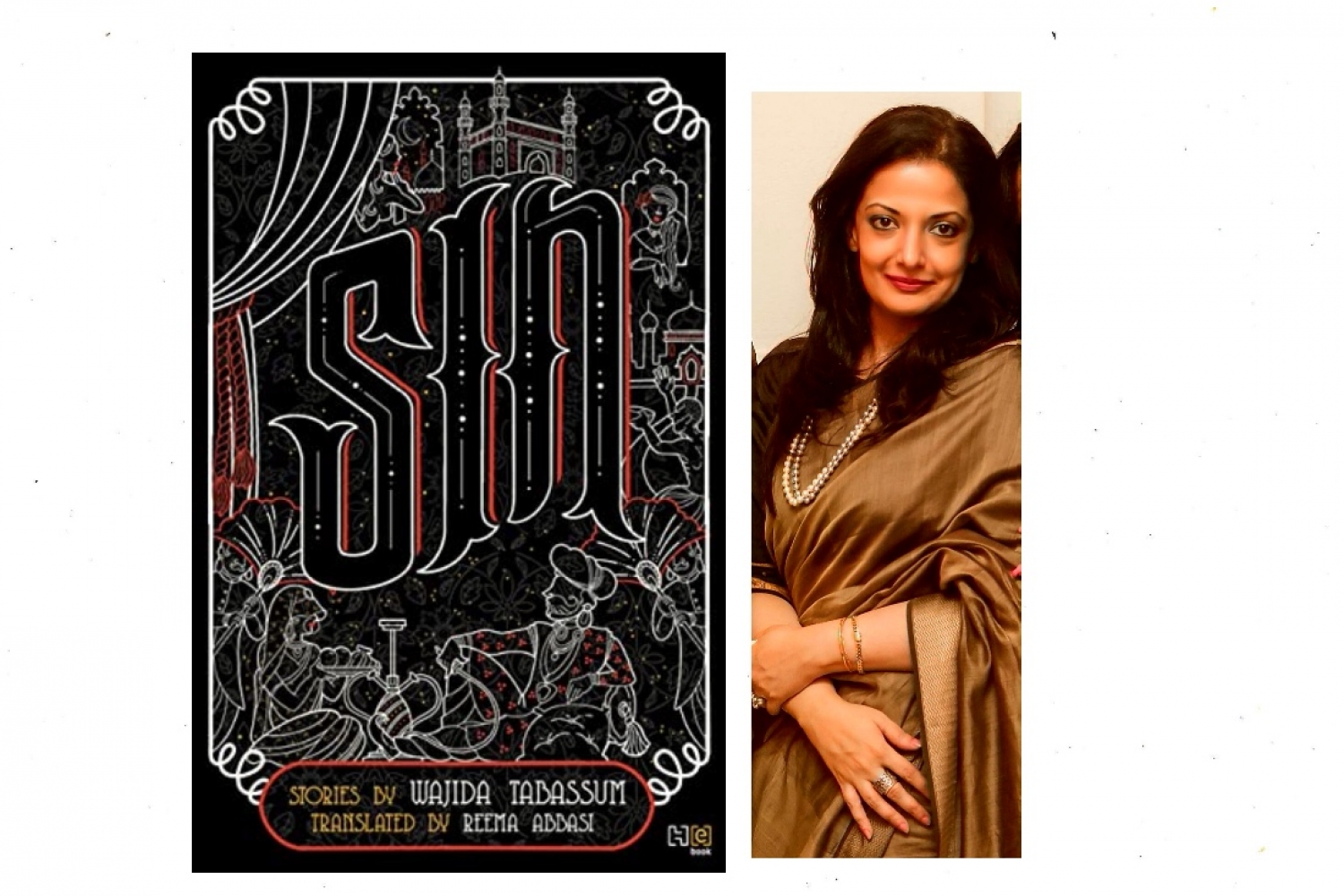

Sin: Stories, a collection of semi-erotic short stories by Wajida Tabassum, translated from Urdu by Pakistani journalist and author, Reema Abbasi, gives us a peek into the world aristocracy of Hyderabad of the 1950s. Categorised into four sections — Lust, Pride, Greed and Envy — these stories probe into the dark side of human nature and societal double standards. Often referred to as ‘female Manto’, Tabassum never got the kind of literary recognition she deserved, rather she lived in immense poverty, facing censure from her relatives, confronting mobs and death threats. Her sharp and evocative prose brings alive the brothels and the harems of royal palaces with searing honesty. Philandering and impotent nawabs, astute begums and ambitious prostitutes populate these stories, at the center of which is the undying spirit of the women who unapologetically own their sexuality and rebel against their cheating and hypocrite husbands with their wit and audacity. These tales of power and passion, politics and betrayal, justice and cruelty, make for delightful and riveting reads.

Translator Reema Abbasi gives us more insight into the creation of the book and the nuances of the translation.

As a reader, when did you first discover Wajida Tabassum’s work?

I first heard of her when Mira Nair’s film Kamasutra - A Tale of Love was released. It was based on Wajida Tabassum’s Uttran, her sole translated story before Sin. However, I can't claim to have given much thought to it or to her at the time. In 2017, after my second non-fiction book was published, I found myself looking for an untouched Urdu writer to translate and it was during the course of this quest that Wajida Tabassum caught my attention. I procured a few stories from Urdu Bazaar, Lahore and was riveted by her contemporary approach, audacity, relevance and robust feminist voice.

What led you to select these nineteen stories?

Firstly, these capture varied circumstances and characters – some tragic and helpless, others deceptively noble and extravagant – with immaculate ease, precision and strength. Second, their culminations are, more often than not, unpredictable and emboldened.This collection is constructed in an order which, one hopes, outlines Wajida Tabassum’s growth as a writer alongside her gradual rise to eminence. For example, the last chapter comprises stories that are particularly masterful in the treatment of plots and the shades of complexities in her characters.

What did the process of translation look like?

As I went to school in England, my speed of reading Urdu is slow. On top of that, Wajida wrote in Deccani Urdu. So the first read took a while as one read quite a few stories to construct a selection of varied themes and protagonists. This too was a challenge as her prime asset is the ability to move her reader, memorably so. The rest of the process was a series of stages – from literal translation to adapting it for another language, in this instance English, and then chiselling the prose.

To ensure that the richness of the socio-cultural milieu was not lost in translation, what kind of research went into it? Did you go to Amravati and Hyderabad as well?

No I didn't. She wrote in the 50s so over seven decades later, society, its mores and settings have altered drastically. Also, the task was to stay true to her descriptions and voice. Not add to it or risk a change.

Wajida Tabassum’s stories have a shocking climactic structure similar to that of Manto and thematic resemblances with Ismat Chughtai’s writings. But how do you think her literary sensibilities differ from other Urdu writers?

I agree that her work shocks and is built around a cataclysmal, stirring lattice. However, as a young girl in an orthodox, impoverished home with little knowledge about the outside world (as chronicled in the chapter, Meri Kahani) she was far removed from their privilege, exposure and freedom. Hence, she relied on observation and a wholesome imagination. Also, Wajida’s language constitutes metaphors, analogies, dialogue, imagery and a turn of phrase that bears no semblance to Manto and Chughtai as it is firmly rooted in old Hyderabad Deccan and its idiosyncrasies.

Since these stories were written far back in the fifties and the sixties, the original language would constitute words and phrases unique to that time and context. How difficult was it to ensure that the essence of her language was not lost on the reader?

Yes exactly. Initially, this seemed insurmountable. But Wajida’s translations have an entirely different audience. The essence, context and allegories were treated with the intention of honesty and preservation for her to emerge as a strong voice of Urdu. Compromises are inevitable given the switch to English. For example, she revels in long, lyrical descriptions, a delight in her medium, but these required brevity for reasons of flow and pace in another language.

What do you think is the most challenging thing about the art of translation?

Staying intimate with the author.

Is the unique and original voice of the author the supreme concern or does the contemporary reader’s expectations and sensibilities also populate the consciousness of the translator?

For me, Wajida Tabassum’s refreshing voice was supreme, because Sin is her introduction in English. However, sensibilities of a modern readership were not far behind. She must appeal to new readers to survive in English and hopefully, other languages.

Are you working on some other translations?

Not at the moment. Ideally, I would like to try my hand at another genre.

Text Saumya Singh

Date 28-04-2022