Photograph: Max Voreacos

Photograph: Max Voreacos

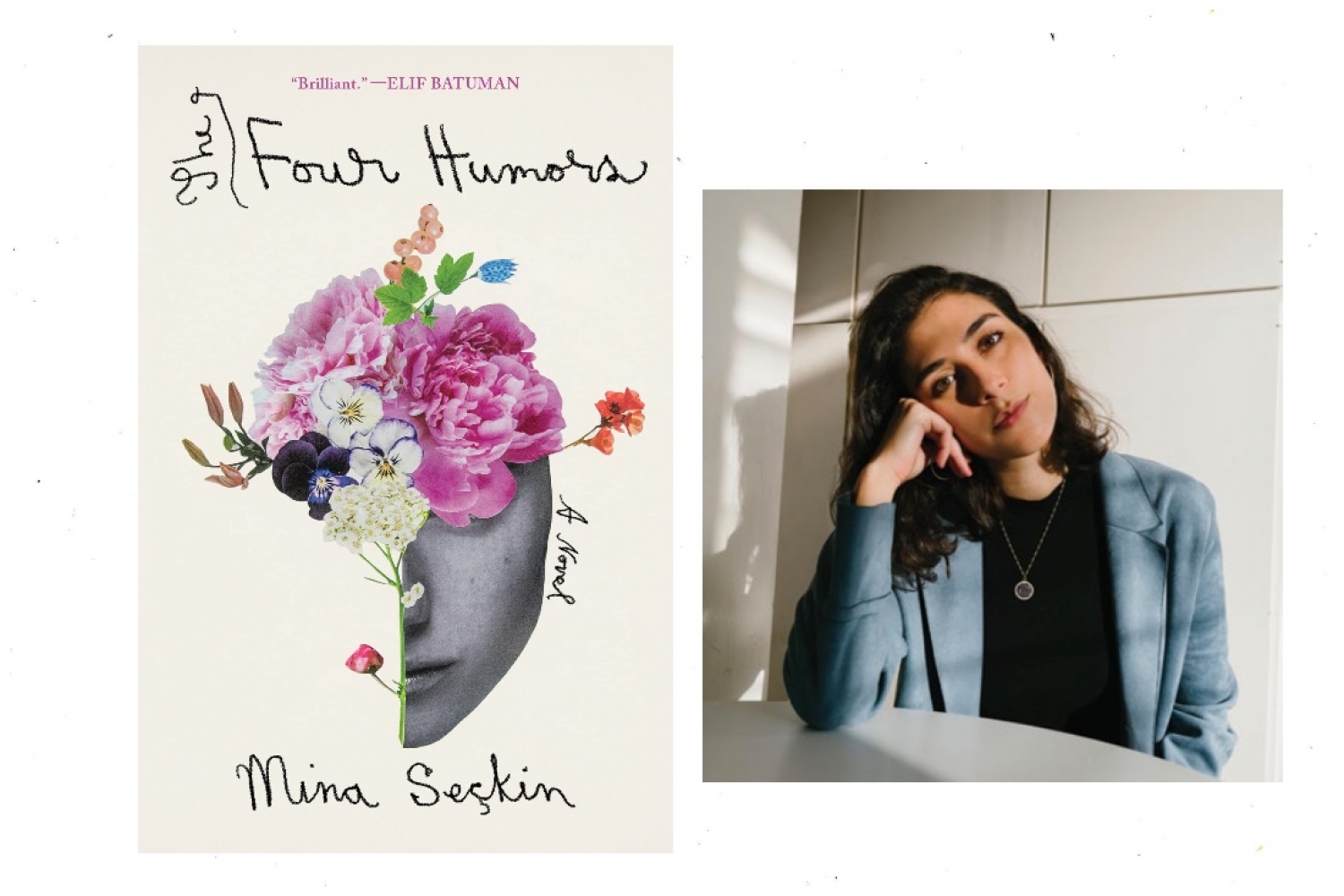

I am elated when, every once in a while, I come across a book with the potential to create a whole new literary canon of its own. Mina Seçkin’s debut book ‘The Four Humors’, flung me into an uncharted teritory of literary fiction, one ingeniously combining,as Mina herself tells me,an “intergenerational diaspora novel and the alienated, cerebral female narrator”. In ‘The Four Humors,’ Sibel, a young Turkish-American woman, finds herself plagued by a stubborn headache. The ailment leads her to the four humours theory of ancient medicine, propelling her away from her set plans for the future, towards a journey both intellectually and viscerally intense. A gamut of facets comprising both Sibel’s past and present unfurl, while Mina acquaints us with the character’s filial history and Turkey’s political past. This year, I’ve had the privilege of reading many books that explore what we inherit from our families — not just physical properties but sometimes entire fates and tragedies. ‘The Four Humors’ is a book that takes this notion and moves further, rather extraordinarily, towards understanding all the mental and physical manifestations of these legacies.

Mina’s remarkable responses, about the book and its making, follow:

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I was an obsessive reader before I ever wrote. I reread my childhood favourites so often that my mom would hide them from me in the hope that I’d read new books as well as do other things that are supposed to be good for a child’s developing mind (for example, lots of math). I knew her hiding places, though. In high school, I started writing poetry and perhaps because I played a few instruments back then, I became possessed by the weight of a single word and rhythm in a sentence. Now, as a prose writer, my ear continues to be the lantern that guides me through a story. It’s always about the music in sentences for me.

What is the core of ‘The Four Humors’ composed of?

At its core, ‘The Four Humors’ is about care. I set this novel in 2014, a year that I find particularly important for both American and Turkish politics. That summer, I was staying at my grandmother’s in Turkey and I developed what would become a chronic year-long headache. At the time, my ninety six-year-old great-grandma with Alzheimer’s was living with us at my grandmother’s apartment because she could no longer care for her health alone. Some nights, my great-grandmother would pee the bed and my grandmother and I would lift her, wash her and change the sheets; she’d call me my mom’s name and I’d reply in kind. I lived in illness that summer — another tumultuous Turkish summer — but I also lived within familial care. The way my grandmother took devoted care of her mother, despite her own Parkinson’s imprinted on me. This act of care proceeded to form the core of this novel. The personal — especially the body — is always political. In ‘The Four Humors,’ I especially wanted to explore how inter- generational trauma and grief is stored in the body.

Tell me about Sibel’s creation.

In jest, my mom once said to me, “Middle Eastern girls don’t get to be depressed”. She was joking and we immediately cracked up in laughter because it was all too true. Middle Eastern daughters are often the emotional and physical caretakers of families and it’s only in recent generations that many have been allowed to forge an independence outside of the expectations of family and marriage. Today and especially in America, they are expected to be incredibly hardworking on top of everything else. I conceived of Sibel as a response to this sentiment. I thought a lot about what Turkish women could and could not do, in the past and today. Sibel, a college student, who is expected to apply to medical school, is not supposed to take a summer off work while also neglecting studying for the MCAT. She’s not supposed to be obsessed with ancient medicine. She’s also an American millennial kid of immigrants, who has access to a more normalised understanding of mental health as well as the expectation that she has to do something worthwhile with the life that her parents gave so much up for.

As a kid of immigrants, I know this tension well. In ‘The Four Humors,’ this emotional tension becomes a physical illness. Through Sibel’s tension of body and mind, I aim to convey that conflict of grappling with the expectations of two different cultures and of carrying those divisions inherent to diaspora within your body.

Where would you locate this book contextually?

I’ve always been drawn to two different types of novels: the intergenerational diaspora novel and the alienated, cerebral female narrator. But there were few novels that did both in equal measures. I often found myself frustrated by clicheÌd narratives about immigrant experiences. I was also frustrated that alienated, cerebral female narrators are almost always white and are often divorced from politics, family and history. ‘How Should A Person Be?’ by Sheila Heti is one of my favourites in the latter category and I found myself asking, yes, but how should a Middle Eastern girl be?

I wrote ‘The Four Humors’ for kids of immigrants, especially Middle Eastern daughters, who are asking this same ques- tion. In terms of my creative process, I slipped into Sibel’s brain with ease, as she is asking the same question I’ve asked as a Turkish-American woman.

Your own roots have certainly affected this book a lot.

While this novel is not autofiction, I drew from much of my lived experience in writing Sibel and the world around her. When my sister first read a draft, she said she felt as if she’d just walked through a fun-house version of our family; certain characters seemed familiar but they were leading a fabricated plotline. I did not want to write about Turkey and I’m still scared to. Writing about Turkey and Turkishness is terrifying, confusing and clarifying for me, which is exactly why I will continue to write Turkish-American protagonists.

During your writing process, were there any other significant influences guiding the path?

There’s a deep oral tradition in Turkish literature; there’s also an all-too-present history of the government censoring literature and jailing journalists and writers in alarming numbers. It was no different in the 70s and 80s, when the leftist movement in Turkey was entirely squashed. When I first read Leyla Erbil’s stellar novel ‘A Strange Woman (Tuhaf Bir Kadin)’ — yet to be published in English — I understood that the story I was telling required sections from the past that incorporated an oral element. ‘A Strange Woman’ tells the story of a young female poet who wants to make a difference in the leftist movement no matter the cost. Every barrier, especially related to gender expectations, stands in her way. Sibel, on the other hand, has a world of access available to her as a modern-day Turkish-American woman but wants to ‘do nothing’. I needed the novel’s structure to force Sibel to enter the past to viscerally understand what generations before her — her once-leftist mother in the late 70s and her grandmother in the 50s — faced.

I also held two favourite novels of mine, ‘A Tale for the Time Being’ by Ruth Ozeki and ‘A Terrible Country’ by Keith Gessen, in my mind as I was writing and editing. In many ways, both novels are an ode to grandmothers and the politics of grappling with a motherland.

I am sure there were many doubts regarding this debut venture. How did you overcome them?

I am in awe of every debut writer. It is emotionally and physically challenging to persevere through countless drafts without knowing that your novel will ever be published. The doubt that I felt over the two years I was writing and editing this book was my greatest challenge; it’s one that can only be counteracted by obsession and faith in the story that you’re telling.

Do you have any words for the readers of your book?

My only hope is that readers will find a likeness and compelling dissonance in this story, as my favourite kinds of novels have the power to do. I also hope that readers won’t attempt to treat themselves using the four humours theory of ancient medicine — I promise it won’t help in combating our general melancholic temperaments.

How have you been coping with the pandemic personally and as a writer?

Oh man, where to begin with how I’ve been coping during this pandemic? I sold ‘The Four Humors’ back in March 2020, one week before the lockdown began in New York. So much of my time at home has been focused on balancing my day job and editing this novel. There have been moments of found joy and I hope for others, too. In general, I tend to use dark and dry humour to engage with our collective political and ecological apocalypse. As a writer, I worry my work is heading towards the more absurdist, as I currently feel it is the only way to properly address our botched state of public health, collective grief and environmental disaster.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

I’m working on a story right now about a woman who moves to Los Angeles to start an ornithology PhD. Like Sibel, this narrator finds she has zero interest in studying! Instead, she ends up in the LA river and becomes obsessed with a great blue heron.

This interview is an all exclusive from our Year end Bookazine. To read more such articles, grab your copy here.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 12-02-2022