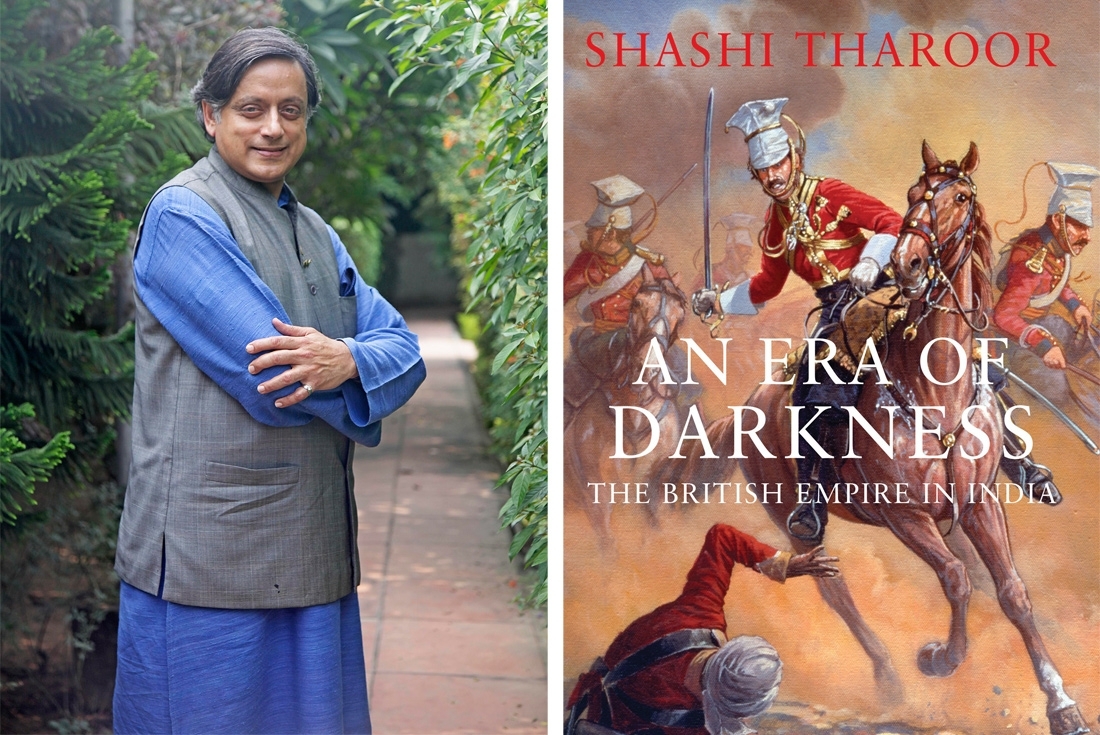

[L to R] Author portrait by Tanuj Ahuja; Book cover

[L to R] Author portrait by Tanuj Ahuja; Book cover

ST. Two ornate tiles in blue carry his initials outside his room, but with that calm demeanour, it might as well be mistaken for a saint’s. Only, this time, Shashi Tharoor has put aside that hat and decided to take on the Raj of the Church that ruled India for centuries. After decades in politics and scholarship in parallel, Dr Tharoor thought it was time the tale be told of how the British extorted every possible form of wealth from India and left her empty, poor and tired. It’s not the most surprising story, but coming from someone with years of smooth dealing in external affairs and deftness at diplomacy, it sure is a hard-hitting hammer.

Between juggling his roles of office, author, father and speaker he presents one of this year’s most-awaited books, An Era of Darkness, that revisits a hellish history in the hope that we keep our lessons for the future. We speak to him about his own life in addition to the book’s.

How would you sum up the last 30 years of your journey?

I wouldn’t! It has, thank God, been too varied to be summed up.

How has your core philosophy and approach evolved over the years?

I’ve always been a liberal, a staunch supporter of political and economic freedom, allied to social justice. That hasn’t changed since my college days; indeed my life has largely confirmed me in my core beliefs. I’ve also been a nationalist with a strong streak of internationalism, and perhaps the balance has shifted more towards then former after my return to India. The one thing that has evolved is a growing rejection of certitudes. Experience has taught me to mistrust absolutes; few things are ever reducible to black and white.

How did the debate at the Oxford Union in 2015 inspire you to write An Era of Darkness?

Well, I honestly did not think I had said anything terribly new. My analysis of the iniquities of British colonialism was based on what I had read and studied since my childhood, and I thought the arguments I was making were so basic that they constituted what Americans would call ‘Indian Nationalism 101’—the fundamental, foundational arguments that justified the Indian struggle for freedom. Similar things had been said by the likes of Romesh Chunder Dutt and Dadabhai Naoroji in the late nineteenth century, and by Jawaharlal Nehru and a host of others in the twentieth. Yet the fact that my speech struck such a chord with so many listeners suggested that what I considered basic was unfamiliar to many, perhaps most, educated Indians. They reacted as if I had opened their eyes, instead of merely reiterating what they had already known. It was this realisation that prompted my friend and publisher, David Davidar, to insist I convert my speech into a short book—something that could be read and digested by the layman but also be a valuable source of reference to students and others looking for the basic facts about India’s experience with British colonialism. The moral urgency of explaining to today’s Indians—and Britons—why colonialism was the horror it turned out to be could not be put aside.

Could you share a blurb on the book?

This is the British blurb, which is shorter than the Indian one:

“In the eighteenth century, India’s share of the world economy was as large as Europe’s. By independence, it had decreased sixfold. In Inglorious Empire, Shashi Tharoor tells the real story of the British in India, from the arrival of the East India Company in 1757 to the end of the Raj in 1947, and reveals how Britain’s rise was built upon its depredations in India.

India was Britain’s biggest cash cow, and Indians literally paid for their own oppression. Britain’s Industrial Revolution was founded on India’s de-industrialisation, and the destruction of its textile industry. Under the British, millions died from starvation—including four million in 1943 alone, after national hero Churchill diverted Bengal’s food stocks to the war effort. Beyond conquest and deception, the Empire blew rebels from cannons, massacred unarmed protesters and entrenched institutionalised racism.

British imperialism justified itself as enlightened despotism for the benefit of the governed. Tharoor takes on and demolishes the arguments for the Empire, demonstrating how every supposed imperial ‘gift’, from the railways to the rule of law, was designed in Britain’s interests alone.

This incisive reassessment of colonialism exposes to devastating effect the inglorious reality of Britain’s stained Indian legacy.”

What helped your research and understanding of the irreparable wrong that Britain has done unto India?

“Who” helped might be more relevant than “what” – for the first time in my writing career I actually received the help of several researchers, who dug up material for me, from colonial-era books and documents, to the latest contemporary scholarship in the field. They are all thanked in my Acknowledgements.

What would you say to British criticism of the title?

Titles and book covers are often reflective of cultural preferences, so it didn’t bother me. I knew that many books by my favourite author, P. G. Wodehouse, bore different titles in England and America. After some back-and-forth, the British publishers settled on Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India. It’s a pretty good summary of what the book is about.

Do you often go back deep into the past? Why do you think such reflections are important and relevant even today, when the present seems disorderly enough?

The British Raj is scarcely ancient history. It is part of the memories of people still alive. According to a recent UN Population Division report the number of Indians over the age of eighty is six million: British rule was an inescapable part of their childhoods. [If you add to their number, their first-generation descendants, Indians in their fifties and sixties, whose parents would have told them stories about their experiences of the Raj, the numbers with an intimate knowledge of the period would swell to over 100 million Indians]. But I do not look to history to absolve my country of the need to do things right today. Rather I seek to understand the wrongs of yesterday, both to grasp what has brought us to our present reality and to understand the past for itself. The past is not necessarily a guide to the future, but it does partly help explain the present. One cannot, as I have written elsewhere, take revenge upon history; history is its own revenge. As India approaches the seventieth anniversary of its independence from the British empire, it is worthwhile for us to examine what brought us to our new departure point in 1947 and the legacy that has helped shape the India we have been seeking to rebuild. That, to me, is this book’s principal reason for existence.

This book seems to be irreverent and ruthless—somewhat a contrast with your roles in diplomacy. How would you juxtapose the two?

Do I have to? Can’t one keep the two worlds apart? I have tried to do so all my life.

What are the biggest challenges you’ve faced along your path?

I suppose a demanding schedule, made worse by my congenital inability to say no to ever-multiplying claims on my time.

Bestselling author, bureaucrat, politician, public intellectual and Father—which of these roles do you enjoy the most and how easy or difficult has it been to switch hats?

Father, undoubtedly. What an unmitigated pleasure it has been to see my sons grow into the fine writers and even finer human beings they have become.

Tell us about some of the most significant things that have helped shape Shashi Tharoor as we know him today.

My parents [a generous, energetic and liberal father and an ambitious, restless and impatient mother]; India; a rigorous education; wide and eclectic reading; the United Nations; a capacity for hard work; and a burning desire to make a difference.

Looking back, is there one thing you would have done differently?

There are a dozen things I’d have done differently. But you can only lead the life you’ve led.

What are the projects you are currently working on and what is next?

Plenty of political projects for the constituency! My publishers would like a somewhat breezy book on us Indians, which I haven’t had the time to think about. And I’m mulling the idea of setting up a foundation that would promote liberalism in India, which seems increasingly beleaguered. God knows we need it….

Our conversation with Shashi Tharoor was first published in our Film Issue of 2016. This article is a part of Throwback Thursday series where we take you back in time with our substantial article archive.

Text Soumya Mukerji