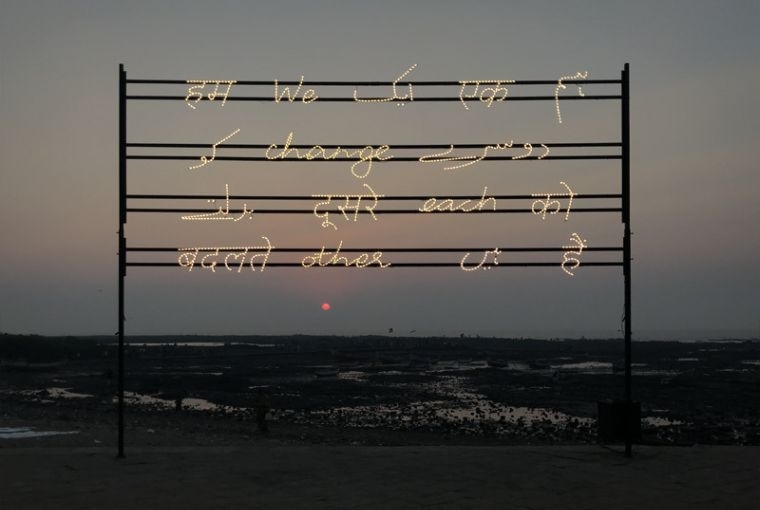

Still They Know Not What I Dream, 2025. LED Neon, 356x130.5x31.5 in Commissioned by Alserkal Arts Foundation, Supported by Ishara Art Foundation, Curated by Fatos Ustek, Photo by Kristina Sergeeva

Still They Know Not What I Dream, 2025. LED Neon, 356x130.5x31.5 in Commissioned by Alserkal Arts Foundation, Supported by Ishara Art Foundation, Curated by Fatos Ustek, Photo by Kristina Sergeeva

I love how silently her art evokes visceral and intellectual emotions, leaving viewers enthralled. I feel each word she expresses and each sound that echoes through her instal - lations. Her art is provocative, it can be experienced, it can be felt. It is not confined to a restricted space or even a frame.

Some of the important themes in her multidisciplinary practice range from politics, sexuality, border regions to gender and identity. She gives meaning to confiscated and lost objects. The term she gives her practice is ‘everyday art’ and to know more about this extremely engaging and moving ideology, I connected with one of the most important names in contemporary art, Shilpa Gupta.

Shruti Kapur Malhotra: Shilpa, you’ve been creating art for the world for over two decades now. When did you realise you wanted to tell stories through this medium?

Shilpa Gupta: Art calls you - like a string that pulls endlessly, and one can sense a knot deep inside. Here in India, at a very young age of sixteen – one is faced with a rather daunting decision about what one would like to do with the rest of one’s life. So yes, that was literally the moment for me, when my whole family expected me to be a doctor or do computer science as I had the marks and I was unable to sleep. I remember those nights of constantly questioning, should I follow my heart or my head? And here I am, still untangling the knots.

I also hardly spoke in school — my friends would ask my mum if I even had a voice. I still like the quiet, but somehow this medium has created an alternative way for me to speak.

SKM: So true. Right from the very beginning, a lot of honesty reflects in your art, especially when you intersperse words and sentences in your art, I live under your sky too, Still they don’t know what I dream, I want to live with no fear amongst others. What is your first memory of when words impacted you?

SG: Somewhere, there is a childhood poetry book that is most embarrassing to read now. While I can’t say what my first memory with words was, I can share an early example of my uneasy relationship with language — and the doubt that comes from trying to define things and, in doing so, limiting what they could be.

For instance, back in ’95–96 at J. J. School of Art, I did a mail art project where I anonymously posted waterproof ink drawings to three hundred people. Each drawing was accompanied by a text with three numbers: the number you received, the one before, and the one after you.

Just like I live under your sky too, where three intertwined languages — those you know and those you might not — suggest that not knowing is also a kind of knowing, the mail art project explored multiplicity and the impossibility of singularity.

Each drawing carried a stamp that read ‘please dispose after use’ — a playful take on the bureaucratic signs and instructions that surround us and that we struggle with, as they constantly tell us what to do and what not to.

As for the drawings, I don’t know anybody who’s got them. I just posted without a return address.

SKM: Just goes to show how your art is so interactive, it’s like the viewer is not only viewing, but also responding, participating, interacting. It’s not only for private collections and museums, it’s also for public spaces like you said, train stations, streets and how people’s responses change from country to country. What is your process, how do you differentiate between public and private?

SG: Actually, it is very organic and rather fluid. Often depending on the context, a particular work will even morph into different forms. For example, Blame can be a bottle that sits on a shelf alongside six hundred others inside a walk-in cabinet saturated with red light — part of an exhibition space. But it can also become a small stack of bottles in an artist-initiated project, or even a single bottle travelling in a taxi as part of a public art project. All this, while the piece originally began as a 100 or so KB file sent via dial-up internet to Pakistan, where it was printed as a single-colour poster and pasted on streets.

While certain works (not all though) can shift form, others face challenges due to infrastructure. For instance, I’ve shown Shadow 3, an interactive video projection, in museums and biennales but I’ve also set it up in a black tent on my neighbourhood street. Convincing the concerned people that it was art and was as challenging as getting the tent made.

We Change Each Other, 2017. Outdoor Animated Light Installation, Courtesy: Shilpa Gupta.

SKM: You talk about conversing through your art but what is the role and purpose of your art and what is the best thing about making art?

SG: The best thing about making art is also the riskiest — learning to go with your instinct. It’s as if something emerges from within you and you are momentarily outside yourself, listening to this other self. Over the years, you learn to trust that other self but it still makes me nervous because every time I start a new project, it never looks like the previous one.

The process comes from a place that feels completely blind — you have to recognise it when it appears. That space — mysterious, fragile and unpredictable — is the most joyous and the most risky part of making art.

SKM: And the role and purpose of your art?

SG: A fundamental question - something I keep returning to. What are images? What is an image? Or an image of an image? When does something become art? What does it gather? What weight does it gather? What value does it gather? And who is the author? When the work leaves your space, who is the author of the work because none of us are real authors, we are all sort of co-authors of everything around us, you know?

Take the Threat soap pieces — they move from my space to a gallery and then into people’s homes, where they sit not as framed objects but in a more domestic, everyday way. That shifts the relationship: it becomes more fluid. You think about the object differently, not in a fixed, binary way of ‘it’ and ‘me’ but in a porous space where you enter the work to see it. It’s not like it’s there and I’m here. But I’m in it and in this world, we are together.

SKM: That’s so true. The fluidity can be seen across many of your works through various mediums and technology. What engages you to try different routes and mediums to come to the same conclusion?

SG: Multiple things. I prefer to stay light and slip away from the weight a particular form can gather in the art world. And I’m continually drawn to the different media that shape our surroundings — technological or otherwise. Interactive objects became websites, then websites led to touch screens and from there to large-scale immersive video projec - tions. My first sound piece in 2001 used a single speaker responding to a sensor, while my most recent works involve speakers orbiting around the viewer. I also have a love–hate relationship with technology. I’m fascinated by how it can seduce but also unsettle and seek to control. Sometimes, a particular site might cause a detour.

SKM: You speak so passionately about your works; even the ones that were done earlier on in your career. I am sure all your works are deeply close to you but in recent times is there one that has touched you deeply?

SG: During the Manchester International Festival, I created a new piece that remains very close to me. It was made with the people of Rochdale and it was so emotionally layered and complex that I haven’t even been able to post about it yet.

I was invited by the wonderful curator Kee Hong, who had recently moved there from Hong Kong. It was his vision to extend the festival beyond the city centre into the boroughs and surrounding areas.

That’s how one afternoon I found myself sitting at a table, surrounded by great food, with ten different community groups that came to meet me. The conversations were very touching. And there was this kind of beautiful hope, curiosity and expectation and also some suspicion about what art can be. That energy and the questions stayed with me.

With two deeply committed human beings, Jodie Ratcliffe and Ruhi Jhunjhun- wala, a prompt was shared, with adults and also teenagers across different community networks in Rochdale. We invited a response via a drawing and text to – ‘Is there some - thing you think about often? What do you miss? What is it?’ The responses were incredibly moving. Rochdale, on the edges of the city, has seen many waves of immigration. I remember a twenty four-year-old refugee from Eritrea who drew a flower and wrote, “I miss my mother. She was a good woman.” A Sri Lankan woman drew the pond she used to swim in as a child. A Pakistani woman drew a charpoi and wrote about slow, relaxed afternoons from her childhood.

We invited local poets to respond to these drawings and stories and then returned to the communities so we could sing the pieces together—in eight languages—rehearsed with the magician Beth Allen.

For example, we worked with a Ukrainian women’s choir spanning three generations. They climbed the stairs and said, “We never thought we were good enough to be recorded.” They had never stepped into a sound studio like most of the other participants. The entire process—almost two years of work—was incredibly intense. And at the open - ing, when everyone gathered, people from so many backgrounds, speaking so many languages, all surrounded by microphones-turned-speakers orbiting with their singing voices—it was truly extraordinary.

For, in your tongue, I cannot fit, 2017-18. Sound Installation. Commissioned by YARAT Contemporary Art Space and Edinburgh Art Festival. Photography Johnny Barrington.

SKM: That does sound so evocative. In the coming year, you are exhibiting in various places. Can you tell us a little bit about them?

SG: Yes, there are a few solo projects and exhibitions I’m working toward. One is a solo at the Hamburger Bahnhof, in Berlin, in a very interesting context — they pair a contemporary artist with Joseph Beuys. It’s quite something because he is such an iconic figure in Germany and Europe and to be placed in conversation with him as a younger artist — and as a woman artist — is both surprising and meaningful. The show is being curated by the amazing team of wonderful Sam Bardaouil and Ulya Soley and opens next March.

Currently on view is a survey show in connection with the Possehl award is currently on view in Lübeck, not far from Berlin in fact. I’ve worked closely with Noura Dirani, who has curated a beautiful presentation of twenty five works with immense sensitivity and care.

Towards the end of the year, I have been invited for a solo in Kyiv in Ukraine, which I am prepared to install long distance and will open a solo experimental project at the recently inaugurated museum on migration called Fenix in Rotterdam.

Next month, I am showing a solo project, A Song in my Head, at the Ginger House in Kochi, around the time of the biennale. Like many spaces in Kochi, it’s a very DIY setting—you literally begin by cleaning the space. But it is worth the effort. I experienced this in 2018 when I showed a sound installation as part of the biennale – such a remarkable mix of visitors both within and beyond the art world.

Shilpa Gupta | Photo by Vani Bhushan

SKM: I would like to ask you one last question, which I am always curious about - through your art, do you pose questions or do you provide answers or do you just highlight the relevant sentiment or the emotion of the time?

SG: I feel the answers are not outside of us. The answers are inside of us and I can’t provide them. Each one arrives on their own. I can only walk half the journey with you. The other half is your journey alone.

The work is about the moment one is in but not limited to this moment — every moment is part of a longer passage of time. It’s not you and me as separate but us. The questions and the answers emerge from a shared space, a collective response.

This is an article from Platform’s latest Bookazine. For more such stories, buy the issue here.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra

Date 14.2.2026