The question of belonging often consumes many individuals. When Anurag Banerjee began contemplating what he considers home, he makes a deeper exploration of his homeland through music, a unifying force ingrained in the very rhythm of Meghalaya and its people. He commenced photographing and documenting the state's musicians, who express their passions and delve into themes of love, grief, community, and activism through their musical endeavors in the form of The Songs of Our People. In this conversation, Banerjee shares insights into his journey of creating the book, his photography, and his reflections on the concept of home.

The book originates from your personal quest for belonging. What motivated you to explore the lives of musicians from Meghalaya specifically rather than your own relationship with the state?

The quest to belong immediately gave way to a quest for community. Because, up until 2020, I did not have a community in Shillong the way I do in Bombay. And it has so happened all through my life that I have made some of my closest friends through my work, either as peers or mentors or people I have photographed. Hence, it was almost an obvious choice for me to work on something through which I can find a community in Shillong. And since Shillong's tryst with music is well known and documented, the answer was right in front of me.

The book originates from your personal quest for belonging. What motivated you to explore the lives of musicians from Meghalaya specifically rather than your own relationship with the state?

The quest to belong immediately gave way to a quest for community. Because, up until 2020, I did not have a community in Shillong the way I do in Bombay. And it has so happened all through my life that I have made some of my closest friends through my work, either as peers or mentors or people I have photographed. Hence, it was almost an obvious choice for me to work on something through which I can find a community in Shillong. And since Shillong's tryst with music is well known and documented, the answer was right in front of me.

Could you discuss the selection process for the artists featured in your book and how they collectively contribute to celebrating Meghalaya and its people?

As mentioned in the introduction of the book, the CAA/NRC protests played a huge role in planting the germ of this idea in my mind—to confront my own and explore the same in my hometown. Since rap and RnB are genres that were born out of protests and people's movements, I gravitated towards the same back in Meghalaya. Hence, rap and RnB form the backbone of the book. But of course, it would be remiss to make a book on music on Meghalaya and restrict it to one particular genre. The book mainly focuses on the contemporary music scene, looking at artists in their 20s and 30s. While stalwarts such as Soulmate and Lou Majaw have been fairly widely written about, I wanted to focus on lesser known names and a majority of the artists in the book are musicians who would be lesser known beyond the borders of Meghalaya and the North East. The idea was also to give enough space to other parts of Meghalaya, such as the Garo Hills and the Jaintia Hills. While my being based in Shillong enabled me to engage more deeply with artists from there, it was also a conscious effort to make the journey to these other parts of the state and speak to musicians there. In these ways, the book offers a contemporary but still holistic picture of the scene in Meghalaya. That artists there continue to pursue their dreams and passions with music despite being heavily culturally underrepesented in the rest of the country or despite the limited resources to support them is testament to their grit and love for what they do. All their stories put together attempts to paint a picture of what Meghalaya is about and thereby celebrate the place that we love so dearly.

As mentioned in the introduction of the book, the CAA/NRC protests played a huge role in planting the germ of this idea in my mind—to confront my own and explore the same in my hometown. Since rap and RnB are genres that were born out of protests and people's movements, I gravitated towards the same back in Meghalaya. Hence, rap and RnB form the backbone of the book. But of course, it would be remiss to make a book on music on Meghalaya and restrict it to one particular genre. The book mainly focuses on the contemporary music scene, looking at artists in their 20s and 30s. While stalwarts such as Soulmate and Lou Majaw have been fairly widely written about, I wanted to focus on lesser known names and a majority of the artists in the book are musicians who would be lesser known beyond the borders of Meghalaya and the North East. The idea was also to give enough space to other parts of Meghalaya, such as the Garo Hills and the Jaintia Hills. While my being based in Shillong enabled me to engage more deeply with artists from there, it was also a conscious effort to make the journey to these other parts of the state and speak to musicians there. In these ways, the book offers a contemporary but still holistic picture of the scene in Meghalaya. That artists there continue to pursue their dreams and passions with music despite being heavily culturally underrepesented in the rest of the country or despite the limited resources to support them is testament to their grit and love for what they do. All their stories put together attempts to paint a picture of what Meghalaya is about and thereby celebrate the place that we love so dearly.

I would like to mention here that I was more than ably guided by Jeffrey Laloo and Jessie Lyngdoh, both musicians and both profiled in the book, and D. Junisha Khongwir, a photographer and educator and a very dear friend of mine who have all been credited as research consultants and it is under their guidance that this book has been possible.

How did you decide on choosing the aesthetics of your photographs?

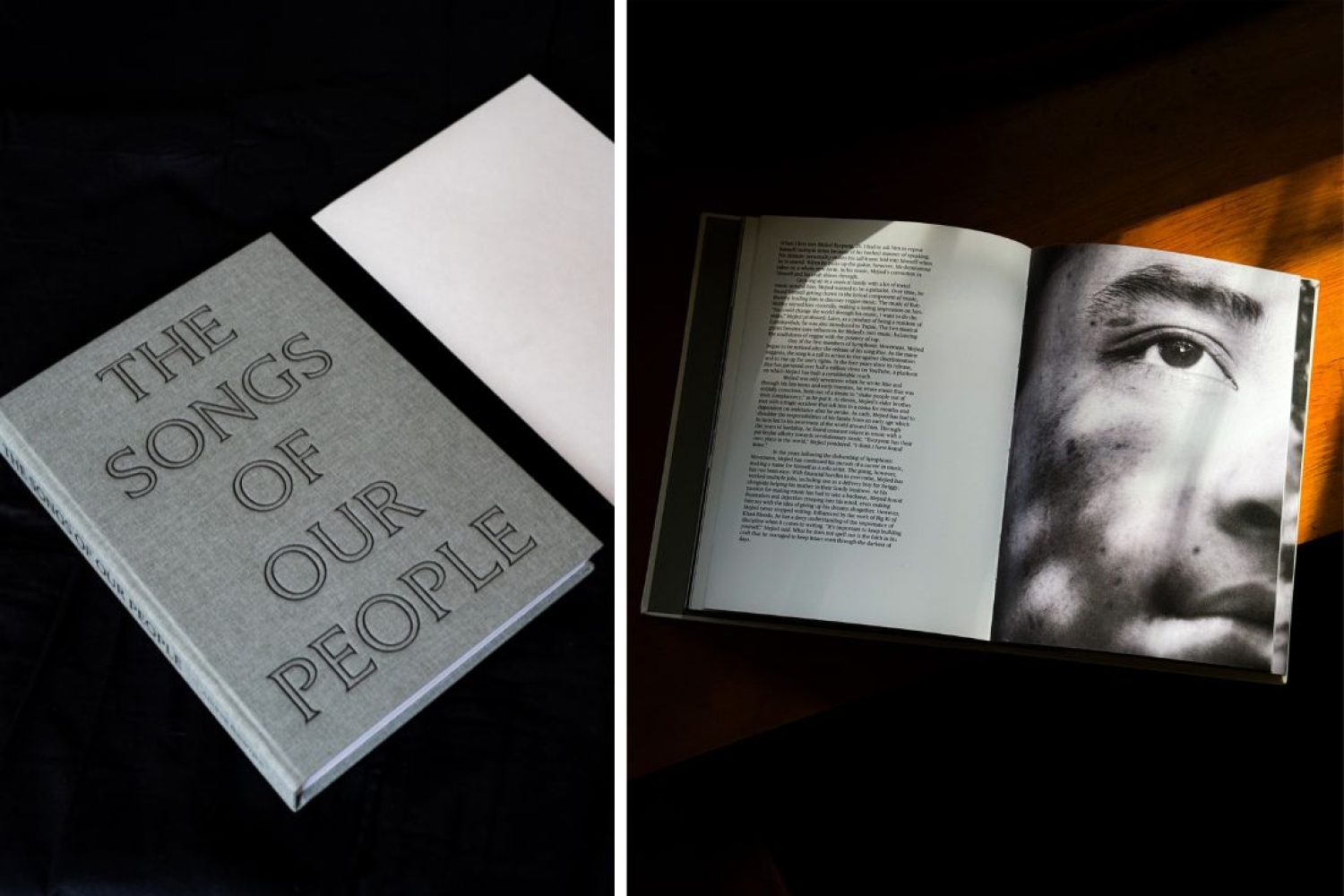

I have never understood what is meant by aesthetic, so please excuse me as I answer this as broadly as I can. With regards to portraiture, which is what this book consists of entirely, I think of my practice as a collaborative one—between myself and the person I am photographing. The first step has to be the creation of a safe space, that the person feels safe around me and also that we make the images at a place where they'd feel comfortable. A lot of times, I left the decision making to the artists themselves. For instance, if you were to look at Maya's images, it was she who decided what she would be wearing and where and how she would like to be photographed. I come in with suggestions and directions and together we arrive at a point that we can both be happy with. The crux of portraiture is trust — one that the photographer has to consciously earn. It requires a lot of work, not just when one is at the shoot but really when one is by themselves. Confront the years of exploitation that is intrinsic to the medium of photography, confront the skewed power dynamics that exists between the person wielding the camera and the one in front of it, and to then break it all down, relinquish the saviour complex entirely. Once you get to that level, one realises that it really is more a life practice than just a mere professional or creative pursuit. That is the kind of portraiture I enjoy the most, the kind where you can tell that the person in the photograph felt safe, trusted the photographer. I will forever aspire to and chase that kind of photography.

I have never understood what is meant by aesthetic, so please excuse me as I answer this as broadly as I can. With regards to portraiture, which is what this book consists of entirely, I think of my practice as a collaborative one—between myself and the person I am photographing. The first step has to be the creation of a safe space, that the person feels safe around me and also that we make the images at a place where they'd feel comfortable. A lot of times, I left the decision making to the artists themselves. For instance, if you were to look at Maya's images, it was she who decided what she would be wearing and where and how she would like to be photographed. I come in with suggestions and directions and together we arrive at a point that we can both be happy with. The crux of portraiture is trust — one that the photographer has to consciously earn. It requires a lot of work, not just when one is at the shoot but really when one is by themselves. Confront the years of exploitation that is intrinsic to the medium of photography, confront the skewed power dynamics that exists between the person wielding the camera and the one in front of it, and to then break it all down, relinquish the saviour complex entirely. Once you get to that level, one realises that it really is more a life practice than just a mere professional or creative pursuit. That is the kind of portraiture I enjoy the most, the kind where you can tell that the person in the photograph felt safe, trusted the photographer. I will forever aspire to and chase that kind of photography.

What do you hope viewers take away from experiencing The Songs Of Our People?

That Meghalaya, and by extension the North East, is as diverse and vibrant a place as any other part of the country. I hope when people read the stories of the nineteen artists, they find parts of themselves in the myriad narratives. I hope it will be a book that people come back to often and hold it close.

That Meghalaya, and by extension the North East, is as diverse and vibrant a place as any other part of the country. I hope when people read the stories of the nineteen artists, they find parts of themselves in the myriad narratives. I hope it will be a book that people come back to often and hold it close.

In what ways did the stories of these musicians affected you while making the book? Did it change your perspective of home?

A few interviews into making the book, I realised that beyond the overarching themes of identity and belonging, a thread that runs through almost each person's story is that of loss, of grief. And how so many people have battled all odds, and continue to do so, just to do what they love the most. It was a humbling, sobering experience and I cannot be grateful enough for the trust that these nineteen artists have placed in me. All I want is for them to feel like I have done justice to it. As for changing the perspective of home—not really, just made me fall deeper and harder in love with the place I call home.

A few interviews into making the book, I realised that beyond the overarching themes of identity and belonging, a thread that runs through almost each person's story is that of loss, of grief. And how so many people have battled all odds, and continue to do so, just to do what they love the most. It was a humbling, sobering experience and I cannot be grateful enough for the trust that these nineteen artists have placed in me. All I want is for them to feel like I have done justice to it. As for changing the perspective of home—not really, just made me fall deeper and harder in love with the place I call home.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 25.03.2024