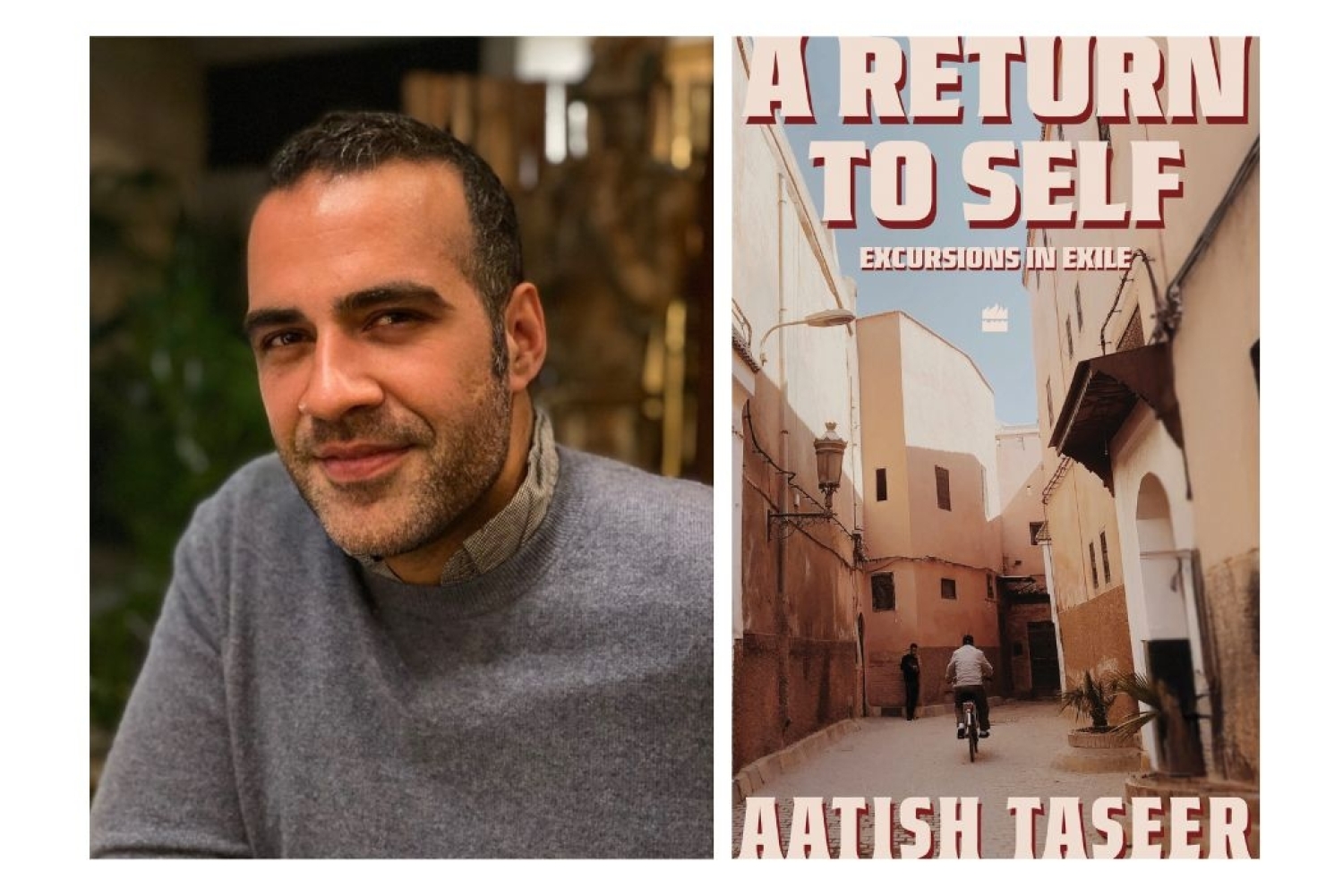

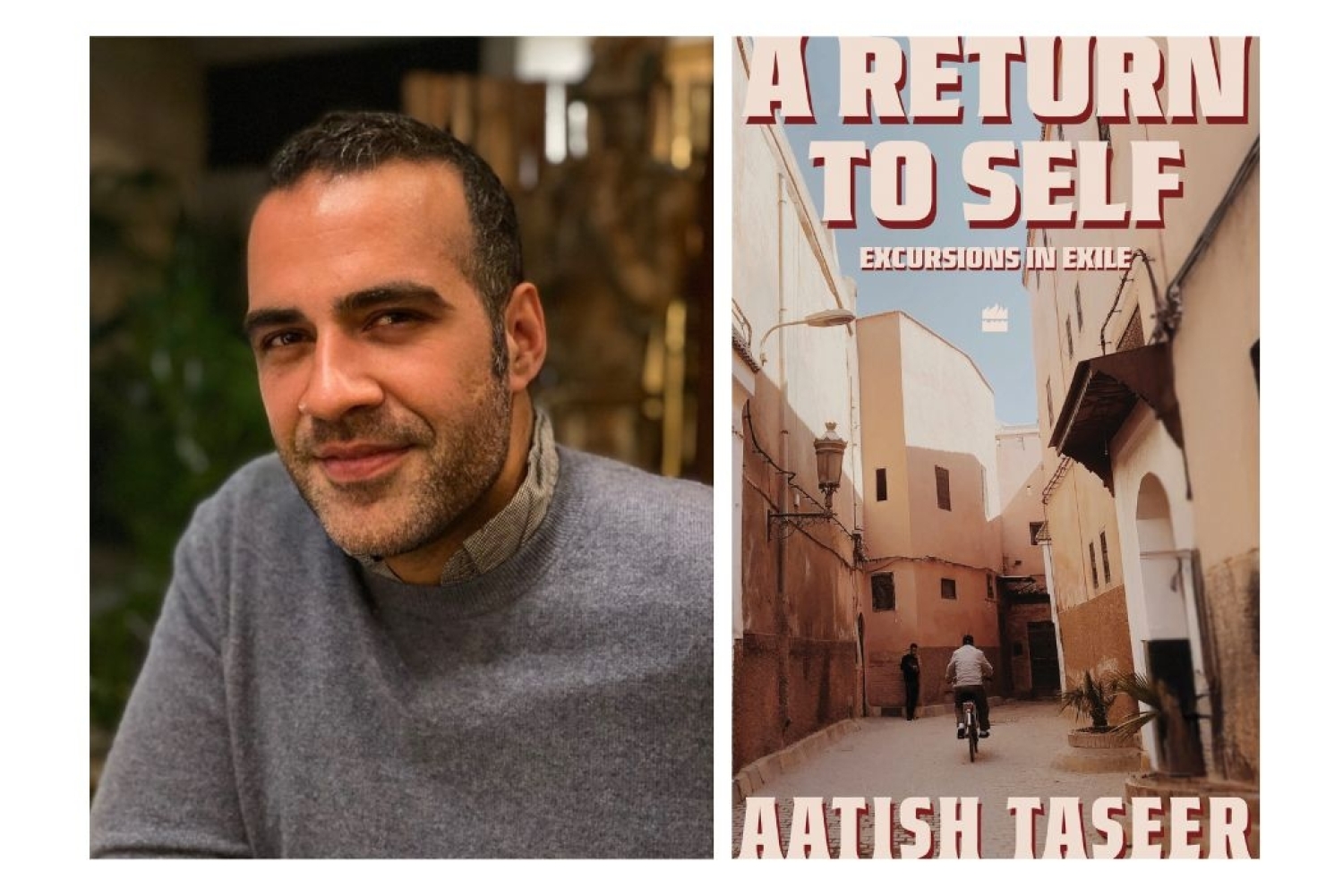

In 2019, the Government of India revoked Aatish Taseer’s citizenship, thereby exiling him from the country where he grew up and lived for thirty years. In his part-memoir, part-travelogue titled A Return to Self: Excursions in Exile, he explores various cultures and identities, which serve as a journey to find his own self after losing access to his homeland. The book grapples with the issue of the idea of home, exile and separation. His meditations are not only informed by his travels around the world, but also his discoveries of memory, selfhood, belonging, sexuality, prejudice and so much more. Istanbul, Morocco, Spain, Sri Lanka and Mongolia are only some of the places that Taseer finds himself writing about. The most interesting facet of this book is the technique with which he confronts his own hopes and ambitions, using the migrations of many people from all around the world. We’re in conversation with him about what it means to be an Indian writer, traits shared by national identities across the world, and the creation of his book.

Let’s start with the background of the book and the events that led to its creation. This book follows a huge, catastrophic event that affected your citizenship and sense of identity. How did it lead to the book, and how did it change your writing?

Some of the travelling I did for this book, maybe one of the essays, had already started before what happened in 2019. I’d had this experience of being a big traveller when I was 25, and then I became very focused on India, on Indian concerns, and wrote around three books that were completely absorbed in what was going on there.

Then suddenly, this other thing happened. Somebody asked me the other day, ‘How is migration different from exile?’ I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but there’s something very concrete about being told, ‘You can’t come back’ or ‘You can’t go home.’ That finality crept up on me.

At the same time, I had this line of work I had to do for The Times that involved being out in the world. I don’t know if I completely understood the mechanism, but the loss of the idea of home and the wonder of being in the world, those two things became the engines, the two arms of a dialectic, that made the book possible.

The idea of home and citizenship seems central to this. Did working on this book challenge your notion of what it means to belong to a place and citizenship, which is essentially defined by a piece of paper?

In a sense, it’s a kind of two-way fraud. The OCI is not citizenship, it’s actually just a visa dressed up as a card. Citizenship itself has always meant very little to me. I was born in England and had British citizenship in an almost totally accidental way. I never thought of myself as English, because it hadn’t been an act of volition.

I’m an American citizen now, and that’s different because it was something I actively did. But the idea of being Indian or South Asian was never small to me. My grandmother brought me to India as a two-year-old. I’m deeply enmeshed in Indian life and writing. My family lives there, and my friends are there. That belonging couldn’t be distilled into a piece of paper.

Even the addition of a Pakistani father was easy to fit into a deeper South Asian sense of belonging. Pakistan, in my view, was another fraud perpetrated on history. India for me was never a piece of paper.

This book moves beyond India, exploring many cultures and countries. Did you notice shared traits in national identities across borders?

If someone reads carefully, they’ll see the concerns in this book are ones I developed in India. In Europe or America, people aren’t necessarily stewing over historical convulsions, or longing to reach back into a past that has disappeared.

The relationship between syncretic religion, being outwardly Christian but with deeper, older beliefs breaking through, is something very recognizable in India. That framework of layered historical tension exists in Bolivia, in Mexico, and in Uzbekistan too. That’s what I mean about having Indian concerns, an Indian writer’s sensibility shapes how I travel and see the world.

“The loss of the idea of home and the wonder of being in the world, those two things became the engines, the two arms of a dialectic, that made the book possible. ”

The title A Return to Self is intriguing. What is the ‘return,’ and what is the ‘self’ you’re reaching for?

It’s a play on a phrase from Ali Shariati, an Iranian cleric active in the 1960s and 70s, who was deeply engaged with Frantz Fanon’s work. His ‘return to self’ meant returning to a cultural identity after the experience of colonization.

I’m using it a little differently. I see the colonial or post-colonial state as a jealous master, imposing fixed ideas of nationality that can limit you. The Indian identity is bigger and more fluid than what the Republic of India can contain.

For me, the return was to a larger canvas, bigger curiosities, and a cosmopolitanism I had excised to meet Indian ideas of belonging. It wasn’t about a privileged Western background, India gave me access to the world. This book was a return to that deeper curiosity.

Were there other writers or works that inspired the form of this book?

I see myself in a tradition of Indian travellers, V. S. Naipaul, Amitav Ghosh, Anjan Sundaram. The Indian traveller has a wonderful quality of containing many selves, the Muslim world is not unfamiliar, nor is Southeast Asia.

There’s also a beautiful asymmetry that a few travellers achieve. Octavio Paz, for instance, came from Mexico, was a diplomat and later ambassador to India, and wrote In Light of India. No European or American could have written that book in its generosity and sympathy. Only someone entering the conversation at an oblique angle could do that. That’s the tradition I see myself in.

What is the future looking like? What are you working on now?

Two things. One is expanding an American journey, which I did in May, into a small essay. Again, it’s in that tradition of outsiders writing about America in ways an American might not.

The other is a bigger project: following Buddhism out of Nepal into Southeast Asia and then further on into East Asia. I’m interested in the relationship between doctrine, the principles of a faith and the compromises it makes on foreign soil, and how it adapts to become a local religion. That tension between idea and locality is fascinating to me.

This article is from our September EZ. Read the EZ here.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 20-9-2025