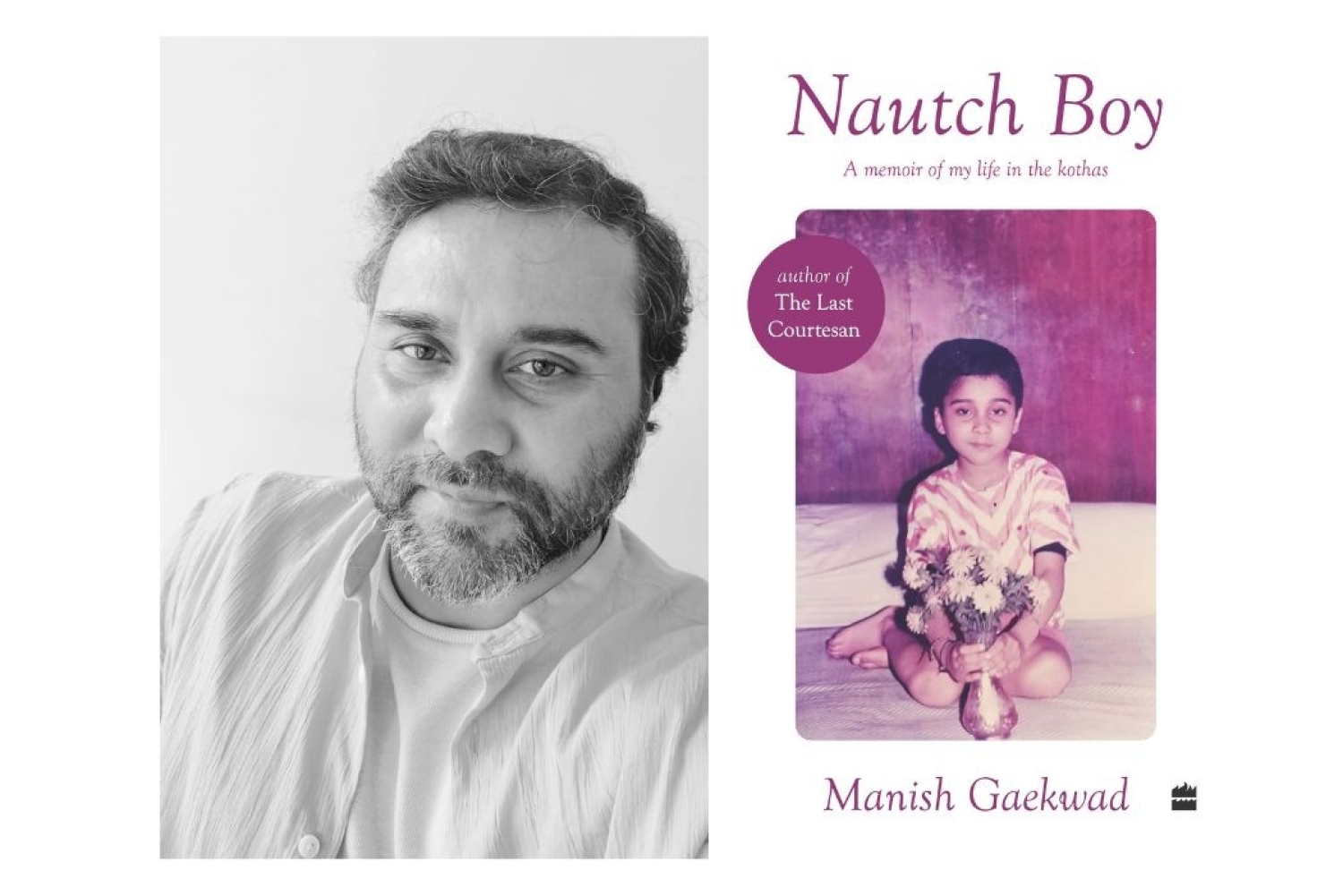

In Nautch Boy, Manish Gaekwad traces his childhood in a courtesan’s quarters, his relationship with his mother and reflects on freedom, inheritance and storytelling as homage. His narratorial voice is honest, intimate and funny, and he uses it to undo stereotypical understandings of the space of the kotha. Following The Last Courtesan, which followed his mother’s story, Nautch Boy is his understanding of his own childhood, spent balancing a life in a boarding school tucked away in the hills along with the glamour of the kotha. We’re in conversation with him on finding voice, legacy, and the dance of becoming a writer.

What made you decide that now was the right time to tell your own story of life in a courtesan’s quarters through Nautch Boy?

Timing works best when it's an accident. I did not plan to tell my story this way. Nautch Boy was initially just a short, closing chapter in The Last Courtesan. While writing it, I realised it didn’t fit with that book’s urgent tone - that story of my mother is a first-person oral account where my role is of the typist. Why interrupt her? Why add another voice to it? So, I had a word with the editor Swati Chopra at Harper Collins and that’s how Nautch Boy was conceived independently to have its own book-length memoir.

What is your relationship with writing, and more importantly the form of a memoir? The form of the memoir calls for a certain undoing of the self, and laying yourself bare to the audience; is there a reason you chose to represent your story this way?

I have no other skill apart from writing. No one taught me to cycle, drive, swim, cook, sew, sing, dance, paint, act, etc. I tried a few of these things on my own, and found myself awful at it, and so I returned to my corner and read a book and wrote a diary from an early age. At nine I said to myself that I want to be a writer. I started manifesting it right away. It’s second to breathing. I’ve unconsciously been training myself as a diarist, a memoirist for a long time. It’s where I get to express my limitations and frustrations and imagine a scenario of limitless possibilities. It’s also where I am free, honest, and can be truer to myself than off the page. So the undoing of the self and laying bare comes easy, naturally to me.

Writing is my best friend to talk to when I need clarity, it’s my therapy without pills. It’s where I go to have fun, discover and surprise myself, and always try to keep it light and not take myself too seriously. And if you are going to tell your story, what better way than to walk in your own dancing shoes?

What does being ‘nautch’ mean to you?

Free, alive, and dancing in my heart, if not extrovertedly with my smooth moves.

Can you tell us about the tension between choosing a ‘better’ future and preserving the legacy you were born into?

My mother chose my future when she put me in a boarding school to protect me from the unstable environment of the kotha. But more importantly, she understood that the atmosphere in the kotha was not conducive for an education, for me to study when so much was happening around; the dance, the music, the constant influx of patrons, friends, and relatives - the party never stopped. And because I went to the boarding school at age five, I was in an elite, English-speaking environment from the very beginning, even before memory forms. It was completely at odds with the undisciplined desi style at home. I only returned to the kotha for a 3-month winter vacation, and observed this colourful world with a detachment, not associating it with my legacy because it was largely in a language alien to me - Hindi - primarily because so much of it was crass, like the cuss words were too much for me to digest. I wasn’t viewing it from the lens of ownership, and because the culture was fading, and being replaced by dance bars and sex work, it wasn’t a legacy I was looking forward to. My mother saw the future and saved me.

“Writing is my best friend to talk to when I need clarity, it’s my therapy without pills. It’s where I go to have fun, discover and surprise myself, and always try to keep it light and not take myself too seriously. And if you are going to tell your story, what better way than to walk in your own dancing shoes?”

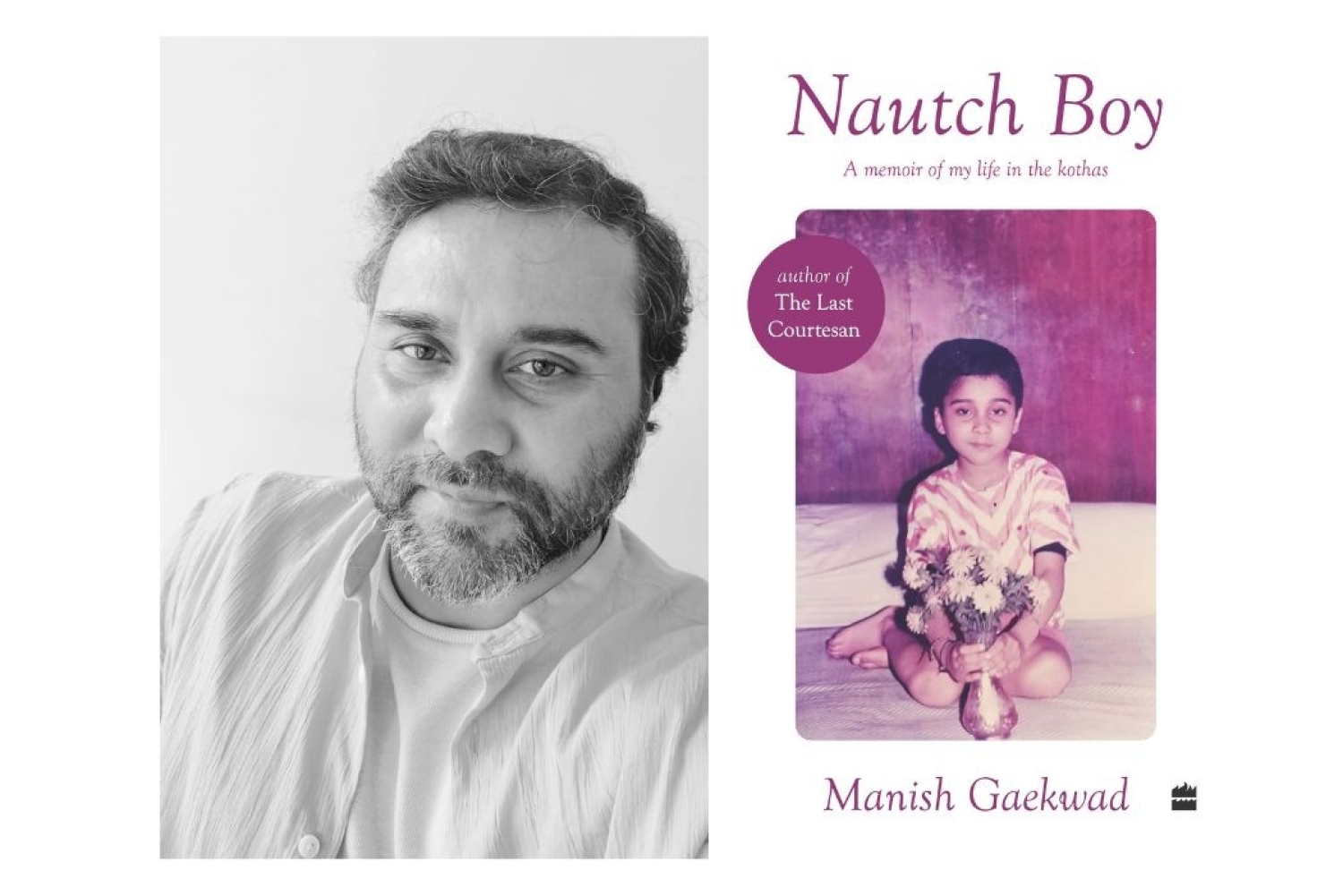

The photo on the cover, of you holding a vase of flowers, is quite intriguing, could you tell us the story behind it?

In the 80s, a local photographer from the mohalla would visit the kotha and offer the courtesans a photo session in their own room, and charge for it. The tawaifs liked dressing up and posing. It’s like Om Puri’s character in Mandi, shooting a willing Neena Gupta, but this photographer was not randy like in the film. No sleazy shots. In this cover photo, I remember two of my aunts asking me to pose with them and then I was asked to pose alone. They asked me to sit and I think the photographer suggested I hold the vase of fake white daisies. I did as told. I hadn’t seen it for some 20 years when I found it in an album which also had the photo of my mother dancing with a Thums-Up bottle on her head. I used that as the cover image for her memoir and so then this one automatically became Nautch Boy - a shy child hinting at the sublime coquetry of the kothas.

Your life growing up in the kothas is inextricably linked to your mother’s — how did writing Nautch Boy and The Last Courtesan pay homage to her?

Well, the whole idea is to give her credit for everything that she was, everything that I am, and one lifetime won’t be enough I guess to thank her for it. More than a homage, she wanted to tell her story. I just happened to be the medium. And I am eternally grateful she did that, in the struggle to establish my credentials as a writer, it’s her giving me the gift of her life to find my voice. Maa hai toh jahaan hai. Warna, kuch nahi.

What were some challenges you faced while putting together a narrative that functioned as a lens into the mysteries of the kotha?

It was easy. She told her story. I told my version. It becomes challenging only if we want to tell but also conceal how we are telling. Memoirs are selective, telling you only the good stuff and reneging on the ugly bits. We didn’t hold back. We are insiders. We want to debunk these so-called mysteries, myths and assumptions so we have to be truthful, authentic and honest to ourselves before we put it out for the public. And we aren’t shy, ashamed or reluctant. We look at our lives with pride and dignity. It’s now for the public to embrace us by acknowledging, learning and accepting a narrative so different from their preconceived notions and ignorance.

What do you hope for readers to take away from the book, and what are you working on next?

That it’s a life worth living and a story worth sharing. I am writing a fictional love story not set in a kotha, so hopefully readers can expect that I have a range beyond my life in the kotha, as an author exploring genres and chasing butterflies.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 1-09-2025